Introduction. Blanche Wittman Charcot’s most famous subject

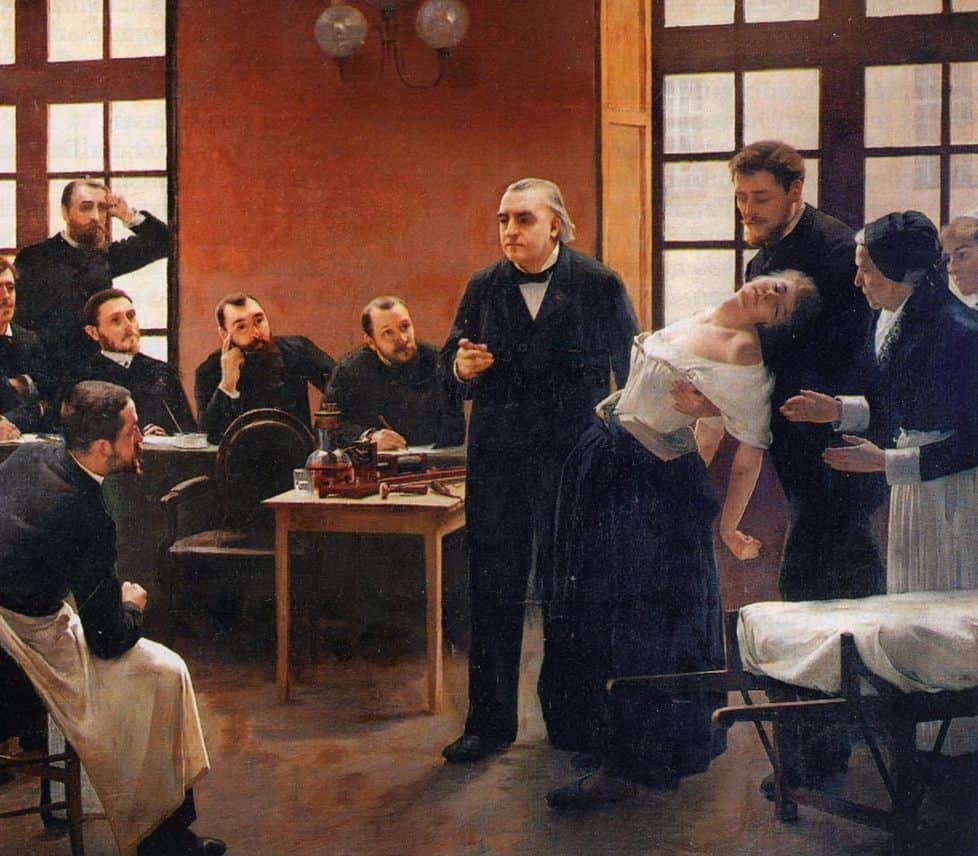

André Brouillet’s well-known painting, “Une leçon clinique à La Salpêtrière,” immortalized Blanche Wittman. She became history’s most due to the artwork’s great success at the Salon des Indépendants in 1887.

In the painting, Professor Jean-Martin Charcot presents his case to an expectant public while indifferent to the commotion behind him. Blanche, a young woman, collapses, under the influence of hypnosis. A careful examination of the artwork reveals her delicate fall, seemingly unconscious, during one of her frequent attacks of “grande hystérie”.

Despite her exaggerated trunk extension and slightly tilted head, she stands with a serene expression and closed eyes, as if lost in a dream. Charcot believed this distinguished the episode from catalepsy. Blanche’s left arm is abnormally extended a characteristic “contracture” often seen in the final stage of hypnosis. Furthermore, her hand exhibits marked flexion.

The duration of the episode remains unknown. However, this detail is crucial in identifying malingering, since someone faking a hysterical attack would struggle to maintain such an uncomfortable position for an extended period.

Cases like Blanche’s have long influenced the diagnostic practices now used in many modern institutions, including leading psychiatric hospital Dubai centers, where both neurological and psychological factors are carefully considered.

Professionals at a reputable neurology clinic Dubai continue to rely on detailed physical signs and patient history to assess conditions like conversion disorder or psychogenic paralysis.

Meanwhile, treatments such as hypnosis therapy Dubai are gaining popularity as non-invasive approaches to managing psychosomatic symptoms and trauma-related conditions.

Such cases also draw the attention of the best psychiatrist Dubai, who integrates both historical insights and current clinical techniques to offer holistic mental health care.

Blanche Wittmann. The “prima donna” at Salpetriere

Blanche Wittmann, the prima donna at Salpetriere, deserves more attention in the development of dynamic psychiatry. While Charcot and his colleagues extensively wrote about their hysterical patients, the voices of the patients themselves are seldom heard.

Prior to her admission to the Salpetriere’s ward for hysterical patients, little is known about Blanche Wittmann’s origin and background. She quickly became one of Charcot’s most famous subjects, earning the nickname “queen of hysterics.”

Charcot’s presentations

Salpêtrière’s presentations were surrounded by an aura of mystery. They began silently, with Charcot, his assistants, and Blanche Wittmann entering the room. Wittmann garnered her reputation due to her predictability in Charcot’s three defined stages of hypnosis: Catalepsy, Lethargy, and Somnambulism.

But it wasn’t just her compliance that captivated audiences it was her extraordinary talent, showcased most prominently in the third stage: Somnambulism, also known as “the suggestible state.” In this state, Wittmann would immerse herself in any scenario assigned by Charcot or even by eager members of the audience. Whether surrounded by rats or snakes, portraying a donkey, or transforming into a lavishly adorned lady of high society, Wittmann breathed life into each role with remarkable authenticity.

These dramatic displays were not mere theater; they illustrated the complexities of psychogenic seizures and dissociative states, topics still studied by modern professionals like a neurologist in Dubai, a psychologist in Dubai, or practitioners offering hypnotherapy Dubai, who continue to explore the intricate links between the mind and body through both clinical and therapeutic approaches.

Blanche’s therapy

Blanche was authoritarian, capricious, and unpleasant towards other patients and staff. At some point, she left the Salpetriere and was admitted to the Hotel-Dieu, where Jules Janet, Pierre Janet’s brother, investigated her and commenced her treatment.

The split personality

During Jules Janet’s modified technique, Blanche reached a new state, resembling a split personality. Her personality II was more balanced and hidden behind her previous self (personality I). This second personality, Blanche II, was aware during demonstrations of the “three stages of hypnosis” when Blanche I was believed to be unconscious.

Blanche Wittmann spent several months in this second state under Jules Janet’s care and showed remarkable and apparently lasting improvement.

Healing

Her subsequent life was described by Baudouin. Blanche returned to the Salpetriere, working in the photography laboratory and later in the newly opened radiology department. She still exhibited moodiness and changeability but remained dedicated to her work in the x-ray department and no longer experienced hysterical attacks. She was reluctant to speak about her past.

Baudouin, who met her personally, mentioned that Wittmann was affected by radiation-induced cancer. Unaware of the dangers of radiology at the time, she became one of its early victims. She had lost fingers and parts of her arms, enduring the agonizing final days of her life with stoicism. She died 2012 as a martyr of science.

Retrospection

Patients’ roles at Salpêtrière have been neglected and remained uninvestigated. Unfortunately, gathering relevant information retrospectively is challenging.

In 1905, 12 years after Charcot’s demise, Alphonse Baudouin, an intern, entered La Salpêtrière and recounted his experiences in his memoir, Quelques Souvenirs de La Salpêtrière, published in 1925.

Baudouin interviewed Blanche and noticed that she seemed to deny her past and responded with anger when questioned about it. He engaged in a conversation with Wittmann, asking her to shed light on the attacks they used to have. She, hesitating for a moment, responded by denying the claims of fakery. She dismissed the notion that they could easily fool Monsieur Charcot, stating that he would silence any tricksters with a single look.

Contemporary perspective on Blanche Wittmann’s case

Medical historians who have studied the case notes have proposed various diagnoses for some patients at La Salpêtrière, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, epilepsy, PTSD, and multiple personality disorder (the latter might count also for Blanche). These conditions were likely exacerbated by the patients’ life experiences before and during their time at La Salpêtrière.

In 2016, S. Giménez-Roldán, presented a paper titled “Clinical History of Blanche Wittmann and Current Knowledge of Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures.” The paper compared Wittmann’s reported hysterical attacks, as documented by Bourneville and Regnard, with Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures (PNES), presenting the results and conclusions. Charcot utilized the susceptibility of hysterical patients to hypnosis as means to differentiate hysterical attacks from epileptic seizures.

The results of recent studies indicate that B.W.’s hysterical attacks share several characteristics with Psychogenic Non-Epileptic Seizures. These include their prolonged duration, presence of repetitive oscillatory body movements during episodes, a history of childhood abuse, and attraction to specific objects.