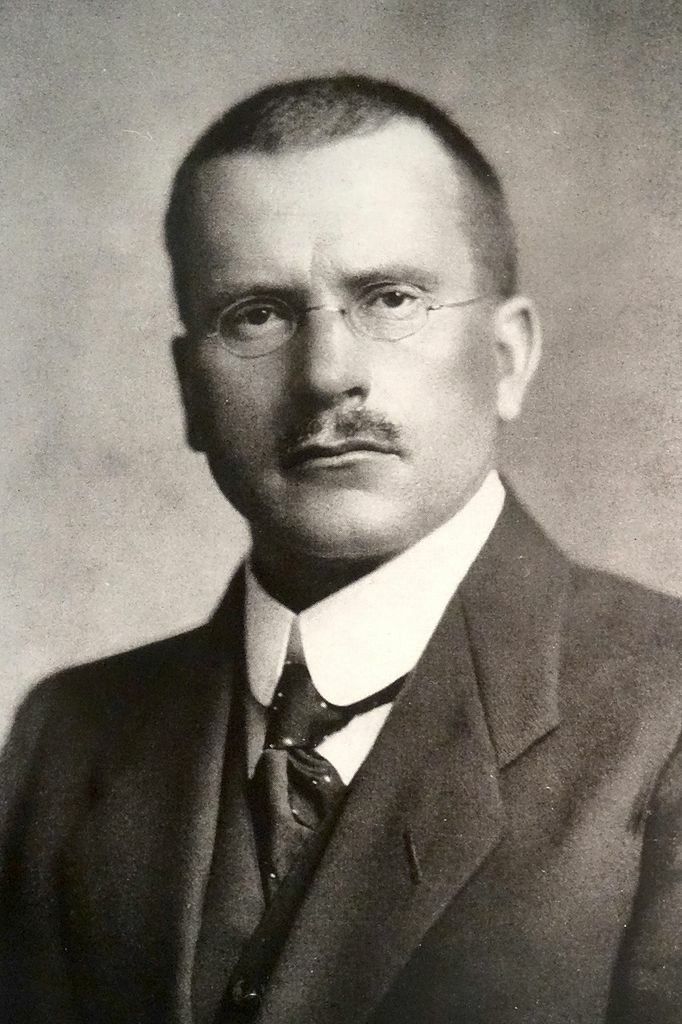

The relationship between C.G. Jung and Otto Gross is an important chapter in the history of psychoanalysis. Jung’s relationship with Otto Gross was marked by a profound initial connection followed by a painful distancing. This trajectory reflects not only the personal dynamics between the two men but also the challenges and the emotional impact on the pioneers of the new therapeutic method. John Kerr’s book and the movie based on it, “The Dangerous Method,” brilliantly portraying the personal drama of the ivolved therapists and their patients.

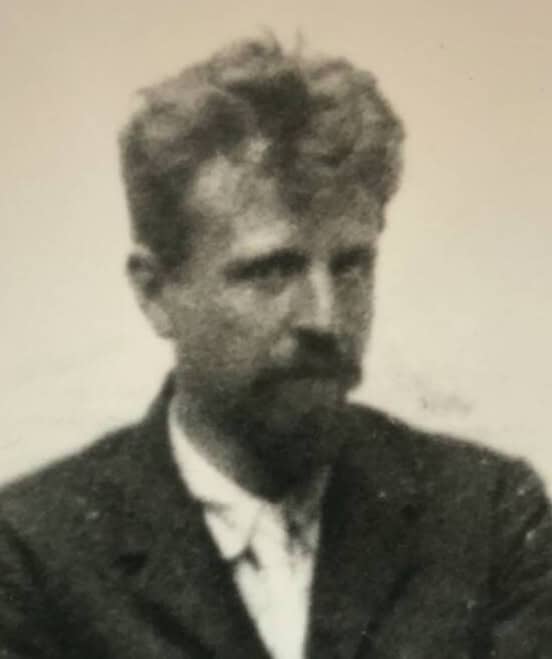

Who was Otto Gross?

Otto Gross (17 March 1877 – 13 February 1920) was an Austrian psychoanalyst and the early supporter of Freud’s psychoanalytical theory before diverging to embrace anarchism and advocate for sexual liberation.

Gross was a radical thinker, whose theories diverged significantly from those of Sigmund Freud. He advocated for anarchy and libertyn behaviour not only in his private life but also within the therapeutic process. Gross’s ideas extended beyond theory into his personal and professional life, blurring the lines between personal liberation and professional practice. Living these ideals, Gross marginalizing himself and his scientific achievements within the psychoanalytical circle not only during his life but also poshumosly being omitted from the history of psychoanalysis.

Despite his initial contributions, Gross faced exclusion from the psychoanalytic movement and was largely omitted from psychoanalytic and psychiatric histories. He ultimately died in poverty.

The recognition of Gross’s contributions was not entirely absent. Figures like Ernest Jones and Sándor Ferenczi acknowledged Gross’s influence; however, their acknowledgments highlight a period when Gross was highly esteemed among his peers.

Gross’s ideas resonated in Carl Jung, whose own theoretical orientations were in a formative stage during their encounters. His intellectual influence on Carl Gustav Jung was profound, but today largely forgotten.

Otto Gross at Burghölzli Hospital

Jung’s close professional relationship with Otto Gross began in 1908. His referral to the Burghölzli Hospital happened due to Freud’s recommendation, where he was analysed by C.G. Jung – and, in turn, Gross analysed Jung.

The mutual analysis with Otto Gross and C.G. Jung influences provided Jung with a profound insight, which later helped him articulate the nuanced dynamics of transference and countertransference. Gross’s impact is evident in how Jung came to view these interactions not merely as clinical phenomena but as integral elements of a dialectical process within therapy, reflecting core principles of Jungian psychology and Otto Gross. This collaboration significantly shaped Jung’s broader Jungian theory, emphasizing a therapeutic space where analyst and patient engage as equals in an unfolding psychological drama.

Jung recognized in Gross many aspects of his own nature, describing him as a “twin brother.” This deep identification suggests that Gross’s perspectives and perhaps his methodological innovations significantly shaped Jung’s thoughts on the dynamics of the psychoanalytic relationship.

Jung’s emotional responses—ranging from admiration to rejection and pathologization—highlight the intense psychological strains that such pioneering analytical relationships can produce, where personal and professional boundaries are continually tested and redefined.

This article explores the critical yet often overlooked role of Otto Gross on Jung, both personally and professionally, shaping psychoanalytic theory and showing the intriguing dynamics of the relationship of these two extraordinary men.

Gross and Jung Mutual Analysis

Despite the initial progress and mutual benefit, Jung grew increasingly aware of the limitations of the therapeutic process with Gross. His realisation of the enduring power of Gross’s infantile complexes, despite their analytical efforts, led Jung to a grim diagnosis of dementia praecox (now known as schizophrenia). This diagnosis marked a turning point in their relationship, reflecting a professional and emotional watershed for Jung.

Jung’s initial reaction to Gross, as captured in his correspondence and case notes, reflects a mixture of admiration and professional curiosity. Gross was not just another patient; he was a fellow psychoanalyst whose ideas challenged and stimulated Jung’s own thinking. This is evident from Jung’s letters to Freud where he mentions that the analysis with Gross yielded “scientifically beautiful results,” indicating the depth and richness of their discussions. However, this high regard is barely noticeable in Jung’s published works, where his acknowledgment of Gross’s influence is minimal, highlighting a discrepancy that hints at deeper undercurrents of conflict and divergence.

The intensity of their sessions is palpable in Jung’s descriptions of their time together. Jung writes about dropping all other commitments to focus on Gross, suggesting a level of dedication and involvement that goes beyond the typical analyst-patient relationship. Gross, in turn, analysed Jung, contributing to significant insights that Jung admits benefited his own psychic health. This mutual analysis is indicative of the deeply reciprocal nature of their interaction, which was both a professional engagement and a profound intellectual exchange.

Gross’ influence on Jung’s work and psyche, revealing the complex interplay of acknowledgment and subtle denial that characterized their relationship.

The Father Complex and the Maternal Struggle

For both Jung and Gross, the paternal figure represented an authoritative constraint that both men strove to overcome. This rebellion against the father was not just a personal struggle but also a professional one, as it shaped their views on psychoanalysis.

The influence of Otto Gross on Jung’s concept of the paternal figure in psychoanalytic theory is multifaceted and profound. In Jung’s essay, “The Significance of the Father in the Destiny of the Individual,” Gross’s impact, though later obscured, was initially prominent. Jung’s decision to eventually omit Gross from his references does not diminish the substantial ideological impact Gross had during their collaboration.

Both men were grappling with the authoritarian legacy of their fathers, which inevitably colored their views on authority and rebellion. This encounter with Gross undoubtedly radicalized Jung’s thinking, leading him to question and eventually redefine the role of the father figure within the psychic development of individuals.

The Influence on Jung’s Emotional and Sexual Relationships

Gross’s impact on Jung extended deeply into the latter’s personal life, particularly in how he managed relationships with women, whether they were his patients, former patients, or acquaintances. Jung seemed to adopt Gross’s controversial practices, possibly prescribing relationships as part of therapy and offering advice on intimate matters, which was an avant-garde approach at the time. This method not only challenged conventional norms but also positioned Jung at the forefront of a more liberated discourse on the role of sexuality and emotional connections within psychoanalytic practice.

The account of Henry Murray, detailed in Robinson’s “Love’s Story Told,” illustrates the complex, emotionally charged dynamics that Jung engaged in, influenced perhaps by Gross’s own unconventional methods. These relationships, which involved significant emotional entanglements and breaches of professional boundaries, underscore the profound impact Gross had on Jung’s approach to handling transference and countertransference in therapeutic settings.

The correspondence and ideas shared between Gross and Jung during the early 20th century were instrumental in helping Jung develop a more elaborate and comprehensive psychological typology. This not only advanced his own theoretical framework but also contributed to the diversification of psychoanalytic discourse beyond the confines of Freudian thought.

Gross’s Contribution to Jung’s Typology

Gross’s theoretical contributions significantly shaped Jung’s ideas on psychological typology. Gross, who often opposed Freud’s theories, particularly the role of sexuality in neuroses, provided Jung with a framework to explore alternative drives within the human psyche.

Gross’s early work on what he termed the ‘Secondary Function’—a concept describing how thoughts associate in the mind —directly influenced Jung’s formulation of introverted and extraverted types. Gross proposed that the way thoughts connect can lead to a broad, shallow consciousness or a narrow, deepened consciousness, concepts that Jung later expanded upon in his own typological theories.

This contribution is crucial in understanding how Jung came to categorize human psychology into two primary types, which became a central aspect of his typology. Gross’s innovative thoughts on psychic variability and the non-linear dynamics of thought processes provided a foundational element for Jung’s later work.

Influence on Jung’s Theory of Transference and Countertransference

The concepts of transference and countertransference are the most important phenomena in the analytical psychology. Transference and countertransference were first described by Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Originally perceived as a hindrance in psychoanalysis, transference evolved into a cornerstone of therapeutic interaction, allowing for the projection of the patient’s feelings onto the analyst. The countertransference is the reverse process, where the analyst projects his emotional complexes into the patient.

Jung’s contributions to these concepts, particularly through his work from 1929 to 1946, demonstrate his innovative approach described in his book “The Psychology of the Transference.”

Gross encouraged a more liberated handling of emotional transference between analysts and their patients, a notion that Jung found both fascinating and troubling. Jung’s ambivalence towards Gross’s approach is reflected in his writings and personal correspondences. While he initially seemed to embrace Gross’s disregard for traditional marital fidelity – as seen in his own relationships with his former patients like Sabina Spielrein and later Toni Wolff – he ultimately retreated from these ideas in later years.

This oscillation between acceptance and rejection of Gross’s ideas highlights Jung’s broader struggle with the concept of sexual morality and its implications for psychoanalytic practice.

Jung’s Bitter Disappointment with Gross

Jung’s subsequent communications with Freud reveal a mix of disappointment and resignation. The diagnosis, coupled with Gross’s abrupt departure from the clinic, escaping “over the garden wall,” symbolises the dramatic and unresolved conclusion to their intensive work together. This incident not only signifies the end of their direct interaction but also underscores the transient impact of their analytical efforts, which, as Jung noted, left “not a trace” behind.

This shift is critical to understanding Jung’s emotional and professional responses. The diagnosis of dementia precox, while clinically justified in Jung’s view, also served as a protective barrier against the intense and perhaps overwhelming connections he had experienced with Gross. Freud’s response to Jung’s efforts—acknowledging the difficulty of the case while emphasising the personal growth Jung achieved through it—further highlights the complexity of the situation. It underscores the psychological and emotional toll it took on Jung, something Freud seemed to anticipate and for which he expressed gratitude that Jung, rather than himself, had undertaken the analysis.

Moreover, Jung’s later reflections on his relationship with Gross reveal a mix of grief and distancing. His description of Gross as “my friend” despite everything and the acknowledgement of Gross’s noble qualities coexist with a portrayal of Gross as a tragic figure whose fate was sealed by mental illness. This narrative allowed Jung to maintain a professional boundary but also hinted at unresolved emotional pain associated with their interaction.

Jung’s Retrospective View on Gross

Jung’s comments on Gross in later years, particularly in communications with other psychoanalysts, was often tinged with resentment and pain. For instance, his comparison of Gross with Sabina Spielrein, another patient with whom Jung had a complicated relationship, suggests a pattern of intense, transformative relationships that ended in pain and professional distancing.

In these cases, Jung’s strategy seems to have involved rationalising his clinical failures or disappointments. The notion of Gross as a “case,” or “madman,” rather than a person in later years points to Jung’s need to depersonalise a relationship that had become too personally challenging.

Despite Jung’s later attempts to minimise Gross’s influence on his work, the intellectual and personal engagements between the two men had a lasting impact on Jung’s development as a thinker and psychoanalyst. Gross’s radical ideas challenged and expanded Jung’s psychological constructs, especially concerning paternal significance, psychological typology, and Jung’s concept of transference.

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Dr. Gregor Kowal studied human medicine at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg, Germany, where he also earned his doctoral degree (PhD). He completed his specialization in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy with the Medical Chamber of Koblenz, Germany. In the following years, he held positions as Head of Department and Medical Director in various psychiatric hospitals across Germany. Alongside his clinical responsibilities, he served as a consultant expert for the Federal Court in Frankfurt, providing psychiatric evaluations in legal cases. Since 2011, Dr. Kowal has been working as the Medical Director of CHMC, the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Dubai, UAE. His specialist training includes extensive expertise in biological psychiatry and psychodynamic psychotherapy.