Carl Gustav Jung Biography begins with his collaboration with Sigmund Freud, as both are regarded as founders of psychodynamic psychology. Not accepting some of Freud’s ideas, Jung went on to create his own therapeutic method, which he called psychoanalytical psychology.

Jung was a man of paradox. On one hand, an empirical scientist who provided an evidence-based proof of Freud’s psychoanalytical theory; on the other, the explorer of parapsychology and esoterics.

He followed his own truth, diverging from the prejudices of his time. He understood that some of his discovieries may not be accepted in his time, but in the future they might be.

Jung saw the psyche as an entity existing on its own, independent from time and space. Such beliefs outcast Jung psychology, which until today is rejected by the mainstreem science.

Carl Gustav Jung. The Childhood

Carl Gustav Jung Biography begins in Kesswil, Switzerland, on 26 July 1875, where he was born to Paul Jung and Emilie Jung (born Preiswerk). His father, Paul Achiles Jung, was the youngest son of a noted German-Swiss professor of medicine at the University of Basel. In contrast, Paul chose to study theology and later became a rural pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church. Emilie, Carl’s mother, grew up in a large Swiss family. Her father, Samuel Preiswerk, was the head of the Reformed clergy in Basel, a Hebraist, author, and editor.

This background helped shape carl gustav jung life and discoveries, which include his development of Jungian psychology. Jung’s theories on the unconscious mind, archetypes, and the collective unconscious revolutionized psychology and laid the foundation for much of modern psychological thought.

This background helped shape carl gustav jung life and discoveries, which include his development of Jungian psychology. Jung’s theories on the unconscious mind, archetypes, and the collective unconscious revolutionized psychology and laid the foundation for much of modern psychological thought.

Jung’s Mother: Emilie Jung born Preiswerk

Prior to Carl’s birth his parents lost two stillborn girls and a son who died after living only five days. In consequence, at the time of Carl’s birth, his mother Emilie suffered from depression.

The marriage of his parents was full of tensions. His mother was eccentric and emotionally instable. Carl notice that she was “normal” during the day but became strange and mysterious at night. Following the Preiswerk spiritualism she claimed spirits visited her room. After having developed a severe depression, she was admitted for few months to the hospital as Carl was three years old. Based on these experiences, Carl associated women with unreliability and men with weakness. Missing a strong father figure in his childhood, Jung later projected his paternal archetype onto Freud who became his mentor.

The father: Paul Achilles Jung

Carl’s father, Paul Achilles Jung, was a warm-hearted man but undecisive and weak. He was at odds with his Christian beliefs. Despite having lost his faith, Paul Jung kept his position in the church also growing more disappointed and depressed.

In his later youth, Jung engaged in intense debates about faith with his father. He described his father in following way:

“The tragedy of my youth was that I saw my father, in a manner of speaking, break down over the problem of his faith and die an early death.”

The issue of religion seemed to occupy him deeply and became more central to his thoughts towards the end of his life.

Fainting spells

At the age of twelve, Jung’s academic journey was marked by a turning point. In a scramble Carl was hit by a school mate and fainted. Upon regaining consciousness an idea appeared in his mind that the fainting was a perfect reason to avoid school. His parents believed that he developed epilepsy and kept him at home. However, hearing his father expressing worries about his future, Carl decided to go back to school and finally he overcome the fainting spells. Decades later, in his autobiographical memories, Jung tried to understand this phenomenon as an expression of a neurosis that served as a way to avoid upcoming tasks and duties. This consideration became a central question for Jung in the individuation process, particularly in understanding how individuals halt their development and maturation steps, thereby blocking their self-realization.

Carl’s introspection abilities

Jung spent his childhood in a parish in rural Switzerland. The family situation contributed to Jung’s withdrawal into a world of fantasy and self-occupation from an early age. Later, Jung would describe and conceptualize this attitude as introversion in his typology. His inner life was marked by vivid dreams and intense fantasies, aspects he later explored in his scientific career.

Growing up in a solitary environment, Jung possessed from an early age a genius for introspection. At the age of seven he used to spend time sitting on a big stone in the garden of the parish. He called the stone “his stone”. Sitting on the stone he asked himself “Am I it, or is it I? Am I the one who is sitting on the stone, or am I the stone on which he is sitting?” (C.G. Jung, Memories, Dreams and Reflections (MDR).

It’s astonishing that a boy of seven years had developed such abstract way of thinking mirroring the psychoanalytical model of projection.

Jung’s number “One” and number “Two” personalities

Living isolated in the parish, Carl read all books he found in his father’s library. He created a secret language and carved symbols and images, without understanding their meaning. While developing his theory of collective unconscious he remembered his childhood experiences and put them in the context of the inherited images and symbols.

Even in his childhood Jung observed himself and noticed the existence of two independent personalities. He called Them his “Number One” and “Number Two” personalities. The first represented Carl’s modern Swiss personality; the second was a personality of a dignified and wise person from the past.

Student years (1895-1900)

After completing his studies at the Basel Gymnasium influenced by family tradition Jung initially wanted to become a preacher. Later he changed his mind and decided to study archaeology. Finally, for opportunistic reasons, he decided to study medicine. However, he was far more interested in theological and psychological topics than in the natural sciences.

As a member of the student society “Zofingia,” Jung gave his first lectures on theology and psychology. As a student, Jung participated in spiritualist séances, which were conducted with the involvement of his cousin, Helene Preiswerk. Jung used the partly experimental nature of these séances for his dissertation.

In 1896, barely a year after Jung commenced his medical studies, his father died and left the family near destitute. They were helped out by relatives who also contributed to Jung’s studies.

In one of his interviews, Jung admitted that medicine as the subject of his studies was chosen for opportunistic reasons. However, thinking about his later speciality, the preface of Krafft-Ebing’s textbook of psychiatry created the decisive impulse.

“This was in 1898, when I began to think more seriously about my career as a medical man. I soon came to the conclusion that I would have to specialize. The choice seemed to lie between surgery and internal medicine…

In preparing myself for the state examination, therefore, the textbook on psychiatry was the last I attacked. I expected nothing of it, and I still remember that as I opened the book by Krafft-Ebing the thought came to me: “Well, now let’s see what a psychiatrist has to say for himself.” …. I began with the preface, intending to find out how a psychiatrist introduced his subject or, indeed, justified his reason for existing at all. …

Beginning with the preface, I read: “It is probably due to the peculiarity of the subject and its incomplete state of development that psychiatric textbooks are stamped with a more or less subjective character.” A few lines further on, the author called the psychoses “diseases of the personality.” My heart suddenly began to pound. I had to stand up and draw a deep breath. My excitement was intense, for it had become clear to me, in a flash of illumination, that for me the only possible goal was psychiatry. Here alone the two currents of my interest could flow together and in a united stream dig their own bed. Here was the empirical field common to biological and spiritual facts, which I had everywhere sought and nowhere found. Here at last was the place where the collision of nature and spirit became a reality.“

C.G.Jung Memories, Dreams, Reflections

Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital

After completing his studies at the University of Basel in 1900 C.G. Jung moved to Zürich and began working at the Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital under Eugen Bleuler. At that time, the hospital was a leading European psychiatric research center and Bleuler probably the most influential psychiatrist of the time.

In 1902 he published his dissertation titled “On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena“. His research was based on the analysis of Jung’s cousin Hélène Preiswerk, a mediumistic medium.

In the following years, he moved to Paris and participated in the lectures of Pierre Janet, a distinct French psychiatrist. Upon his return to Zurich, he worked as the assistant of Eugen Bleuler. In the years 1905–1913, he served as senior physician at Burghölzli and as a lecturer in psychiatry at the University of Zurich.

Word association experiment

In 1904, C. G. Jung, then senior physician at the psychiatric clinic of Eugen Bleuler, along with his then psychiatric assistant Franz Riklin, published for the first time on the so-called “association experiment.”

The word association experiment is an experimental psychological test that can be traced back to such great names as Francis Galton or Emil Kraepelin in the 19th century. This method is known today as the Word Association Test (WAT).

The method of the association experiment was simple. The patient was exposed to a set of words being asked to answer with a single associated word. The innovative method applied by Jung was searching for “what was not there” and why certain answers were distorted. Jung discovered that disturbed, illogical, or peculiar responses stemmed from emotionally charged associations that were unconsciously repressed by the subject due to their disagreeable nature.

Jung coined the term “complex” to describe these repressed emotional clusters. The word association experiment was the first scientifically based method supporting Freud’s psychoanalysis and, in particular, the mechanism of repression.

The test opened for Jung a fruitful academic career, earning him the invitation to Congress at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, in which he participated with Freud.

Private practice and lecturing activities

In 1913, between 1911 and 1913, Jung was president of the International Psychoanalytical Association. After braking with Freud, he gave up on his university career and opened his own private psychotherapeutic practice in his newly built haus in Küsnacht (Zurich).

From 1933 to 1941, he lectured in psychology and served as a professor at the general sciences department of ETH Zurich. From 1944 until his death, he was a professor of medical psychology at the University of Basel (teaching ceased in 1945).

Marriage

Jung had married Emma Rauschenbach (1882–1955), the daughter of a rich industrialist. Between 1904 and 1914, they had five: four daughters and a son. Initially, their residence was a flat in Burghölzli. However, in 1908, they relocated to a splendid house they designed and constructed by the lakeside in Küsnacht, where they would spend the remainder of their lives.

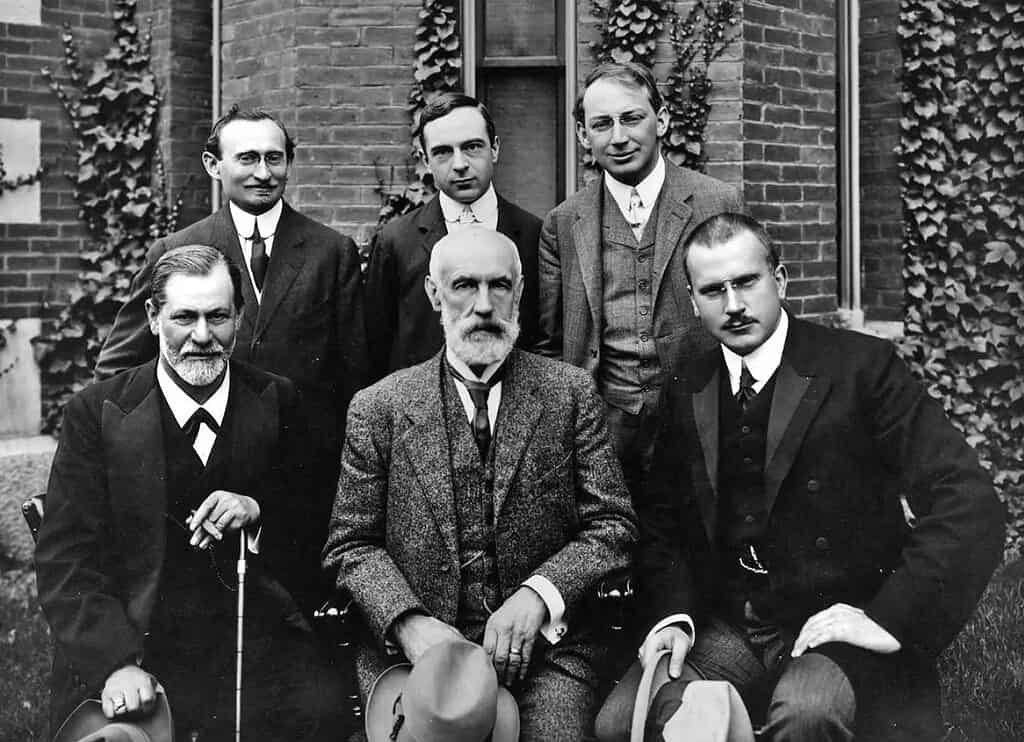

Friendship with Sigmund Freud

In 1904, Jung published “Studies in Word-Association” and sent its copy to Sigmund Freud. One year later, he visited Freud in Vienna. From that time onward, he established a close friendship and a strong professional association with Freud. For six years he was the advocate of psychoanalysis, and in 1912 he became the president of “The International Psychoanalytic Association.” In the same year, Jung published his pivotal work, “Psychology of the Unconscious.”

In this book, Jung expressed different view on the libido, questioning Freud’s dogma. Consequently, their personal and professional relationship went to pieces.

Breaking with Freud’s ideas

During this transformative phase, Jung rejected Freud’s reductionist theories and laid the groundwork for his own psychoanalytical theory. With the vigour of someone emerging from a creative illness, Jung delved back into the realms of myth, philosophy, and religion, seeking objective parallels to his experiences.

He argued that in the pursuit of understanding the human psyche, one must consider more than just sexual drives and repressed desires. Through a comprehensive historical review, he identified two fundamental psychological orientations: introversion and extraversion.

Jung’s and Freud’s Middle Age Transformation

After the culminating break with Freud in 1913, Jung went through a difficult and pivotal psychological transformation resembling a psychosis. In the 1890s, Sigmund Freud suffered a similar personal breakdown, which he cured with his own self-analysis.

On their recovery, both men published major and original books. During this phase, Freud discovered the basic principles of psychoanalysis and published his book “The Interpretation of Dreams,” which appeared in 1900 when he was 45. Similarly, Jung’s pivotal work, “Psychological Types,” was published in 1921 when he was 46.

If the six years of their friendship were a period of discovery and preparation for Jung, for Freud it was a time of retrenchment, during which he became increasingly intolerant of those who would revise his ideas, which for him had become matters of indisputable fact.

“Confrontation with the Unconscious”

During Jung’s critical phase, the actual nature of his experience remains a topic of debate. Henri Ellenberger, the author of the monumental work “The Discovery of the Unconscious,” proposes that Jung underwent a “creative illness” much like Freud at a similar age. This condition emerges after intense intellectual activity and resembles neurosis or, in severe cases, psychosis. The individual struggles with unresolved issues, feeling isolated and beyond help. The disturbance can endure for four to five years. Recovery occurs spontaneously, accompanied by euphoria and a profound transformation of personality. The person gains insights into important truths and feels a duty to share them with the world. Jung’s experience mirrors that of shamans, mystics, artists, writers, and philosophers. The theme of the descent into the underworld and the return also occurs in the epic of Gilgamesh, Virgil’s Adenoid, and Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Jung’s Contribution to Science

As a senior physician at Burghölzli, Jung demonstrated the existence of autonomous unconscious complexes using the word association experiment, providing the first evidenced proof for Freud’s psychoanalytical theory. From 1907 to 1913, he worked with Sigmund Freud, helping Freud’s psychoanalysis to gain international recognition.

In 1912, in his paper “Transformations and Symbols of the Libido,” C.G. Jung’s work expressed a view that sexuality is merely one of several expressions of psychic energy, the Libido, rather than its central source, as Freud suggested. The publishing of this work initiated the break of both mean’s friendship.

Carl Gustav Jung’s analytical psychology

C.G. Jung is recognized as a pioneer of modern psychology, transcending the narrow confines of behavioural psychology to address themes relevant to both the spiritual and instinctual lives of humans. He founded his own school of thought, which he called “analytical psychology,” differentiating it from Freud’s psychoanalytic theory.

Collective unconscious and archetypes

The cornerstones of Jung’s theory are such concepts as the “collective unconscious,” the “Archetypes” and the “Self“. According to Jung, the collective unconscious exists in the depths of the human psyche. He saw it as the container of the condensed knowledge and experiences of our species. The collective unconscious is constellated by instincts and archetypes.

Jung described distinct archetypes. The most important of them are the “Self” “Shadow,” “Old Wise Man,” the “Great Mother”, the “Animus” and “Anima” and more. As proof of their existence is the fact that similar themes appear in customs and mythologies in different cultures. The main aim of the analytical psychology is examining the patient’s relationship to the collective unconscious.

Jung supported his studies with extensive studies of mythologies, religions, and ethnological expeditions to the Pueblo Indians in New Mexico and the natives in Kenya.

The Ego and the Self

Jung introduced the term “Self,” representing the unified consciousness and unconscious. According to him, in the new born there is only one psychic structure, the “Self.” Throughout our socialization, individuals develop an ego-consciousness, separating it from the unconscious. He proposed two centers of personality existing in mature individuals, the Ego and the Self. According to Jung, the “Ego” is the canter of consciousness, whereas the “Self” is defined as the center of the total individual’s psyche.

The term “Individuation” describes the process in which Ego integrates various aspects of one’s unconscious. Completing the process of individuation is the ideal aim of a human’s life and the warranty of one’s undisturbed development.

Jung’s typology

The result of Jung’s intensive research was his typology described in the book, “Psychological Types.” According to Jung, people can be divided into two groups: those with an extroverted orientation and those with an introverted orientation. This distinction refers to the fundamental direction of an individual’s engagement with the world and with themselves. In simple terms, “extraversion” and “introversion” refer to an outward or inward orientation, respectively.

Besides these two orientation types, Jung distinguished four fundamental psychic functions: thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuiting. They could be described as activities of the psyche, reflecting how people process sensory perceptions or psychic content in their consciousness.

The function of thinking is a biological adaptation to the logical aspect of the world organized in terms of phenomena such as causality, space, and time. Intuition corresponds to the world in terms of its possibilities, sensing to the sensually given world, and feeling to the world as reflected in one’s own pleasure or displeasure. In each individual, one of these functions usually dominates.

By combining the two orientation types with the four psychic functions, eight function types emerge. This classification is generalized, yet it effectively captures the concrete cases encountered in psychiatric practice. Jung’s typology is still used, for example, in Myers Briggs personality test.

Synchronicity

One of his last major works was on the concept of meaningful coincidences, “Synchronicity” (Nature Explanation and Psyche, 1952). In 1921, he wrote a major work on “Psychological Types,” where he described and coined the terms introversion and extraversion and explained the psychological functions of thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition. The evolution of his science is contained in his monumental work, the Collected Works, written over sixty years of his lifetime.

In his memoirs, “Memories, Dreams, Reflections” (published in 1962), Jung revealed not just his observations of others but his own personal experiences.

Read More about Jungian Psychology

- Carl Gustav Jung. A Short Biography

- Psychology of Carl Gustav Jung

- The Collective Unconcious

- The Self

- The Individuation

- The Archetyps

- Archetyps. The Redicovered Theory

- The Ego and The Persona

- The Shadow

- The Animus and The Anima

- The Archytypal Neurosis

- Jungian Psychology and the Brain Structure

- Brain Evolution and Psychology

- Synchronicity

- Jungian Dream Analysis

- Freudian and Jungian Models of the Psyche

- What is Psychoanalytical Psychotherapy

- C.G. Jung and Otto Gross

- C.G. Jung Psychological Types

- C.G. Jung’s Word Association Test

- The Spiritual Aspect of the Psyche (Jungian View)

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Dr. Gregor Kowal studied human medicine at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg, Germany, where he also earned his doctoral degree (PhD). He completed his specialization in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy with the Medical Chamber of Koblenz, Germany. In the following years, he held positions as Head of Department and Medical Director in various psychiatric hospitals across Germany. Alongside his clinical responsibilities, he served as a consultant expert for the Federal Court in Frankfurt, providing psychiatric evaluations in legal cases. Since 2011, Dr. Kowal has been working as the Medical Director of CHMC, the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Dubai, UAE. His specialist training includes extensive expertise in biological psychiatry and psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Sources

Collected Works of C.G. Jung, The First Complete English Edition of the Works of C.G. Jung. Archived from the original on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-20. Taylor & Francis

Jung, C.G.; Aniela Jaffé (1965). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Random House. p. v.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Psychology and the Occult. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978

Bair, Deirdre (2003). Jung: A Biography. New York: Back Bay Books.

Gay, Peter (1995). Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac.

The BBC interviewed Jung for Face to Face with John Freeman at Jung’s home in Zurich in 1959

Carl Jung (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, Volume 9, Part 1. Princeton University Press