The Salpetriere School, in contrast to the Nancy School, had a strong organization led by Jean-Martin Charcot, a powerful figure and renowned neurologist. Actually, talking about “Salpetriere School” would be an exaggeration. It was Charcot, who dominated the scene transforming Salpatriare, known until then as the “grand asylum of human misery” to the most important psychiatric centre in Europe.

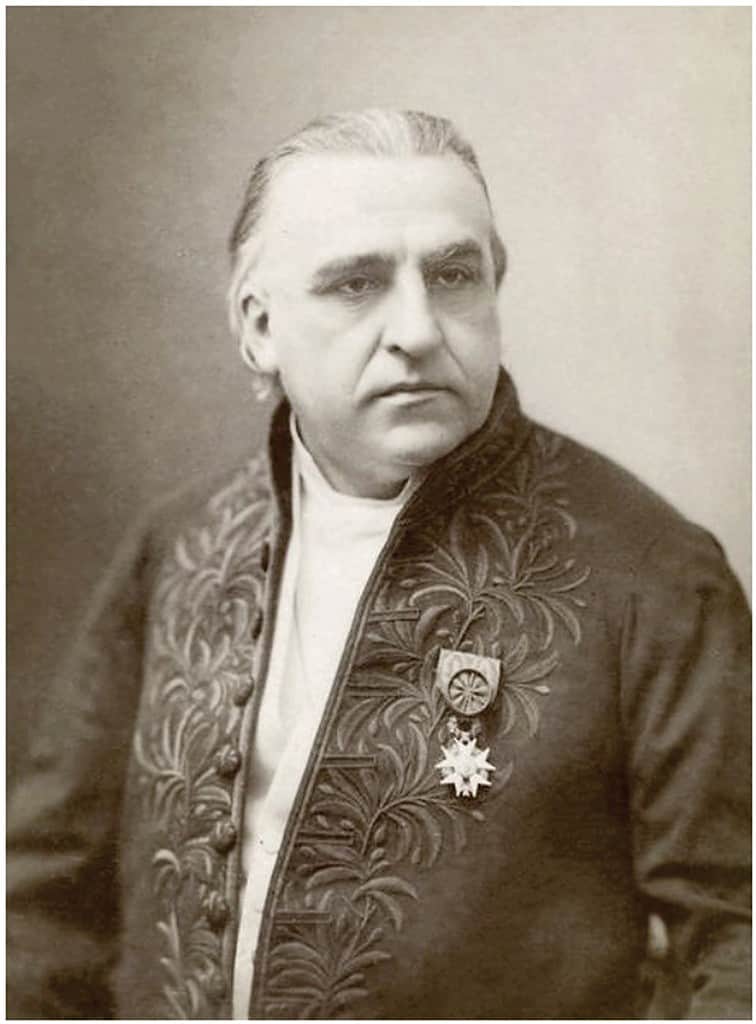

Jean-Martin Charcot

Jean-Martin Charcot (1835-1893), born in post-revolution Paris, grew up in humble conditions. With limited resources, his father made a decision that the most academically successful child would pursue higher education. Charcot graduated from the University of Paris in 1848. Following this, he embarked on an internship at L’Hôpital Salpêtrière in Paris. While pursuing his career as an anatomo-pathologist, Charcot’s breakthrough came in 1862 when he became the chief physician at Salpetriere’s largest section, initiating intensive case studies, autopsies, and laboratory work. Within eight years, from 1862 to 1870, Charcot made groundbreaking discoveries, establishing his status as the leading neurologist of his era.

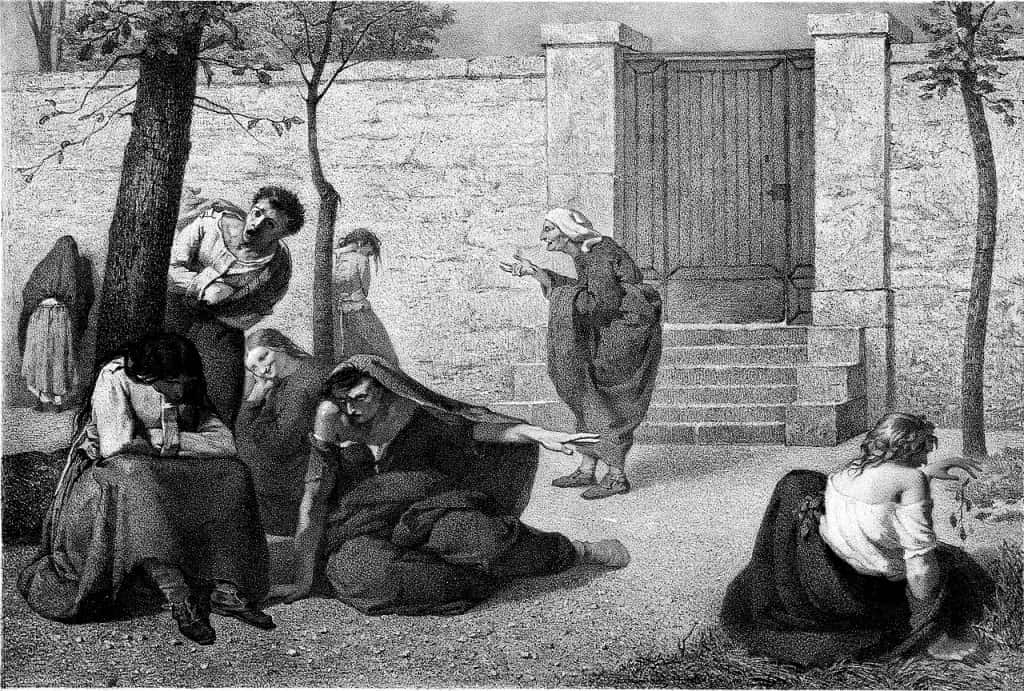

Salpetriere

Salpetriere, was far from an ordinary hospital. It resembled a self-contained city, with seventeenth-century-style buildings, streets, squares, gardens, and a beautiful old church. Moreover, the institution held historical significance, having been associated with Saint Vincent de Paul’s charitable endeavours. It was later transformed by Louis XIV into an asylum for beggars, prostitutes, and the mentally ill. The infamous September Massacres of the French Revolution took place there, and it was where Pinel implemented revolutionary reforms in mental healthcare.

Charcot’s reforms at Salpetriere

Before Charcot’s time, the Salpetriere had been relatively obscure among medical students, and physicians were not enthusiastic about being assigned there. Already as a young medical resident at Salpetriere, Charcot recognized its potential for researching rare neurological diseases. Through his scientific wizardry, he transformed this historic institution into a Temple of Science.

In 1870, he assumed additional responsibilities for a special ward housing women with convulsions, aiming to distinguish between hysterical and epileptic seizures.

Despite its outdated facilities lacking laboratories, examination rooms, and teaching resources, Charcot, with his unwavering determination and political connections, established a comprehensive treatment, research, and teaching unit. He handpicked his collaborators, creating consulting rooms for various specialties like ophthalmology and otolaryngology, along with laboratories and a photographic service.

He later he added an anatomo-pathology museum, an outpatient department that admitted men, and a large auditorium.

Charcot wielded absolute control over the school he had established, and his lectures were meticulously recorded by students and published in the numerous medical journals he had founded. At one point, his approval became a prerequisite for appointments to the Paris medical faculty.

Charcot’s Three Paths of Career

Firstly, Charcot made valuable contributions as an internist and anatomo-pathologist, advancing knowledge in pulmonary and kidney diseases. His lectures on diseases of old age became classics in the field of geriatrics.

Secondly, in neurology, his second career, he made outstanding discoveries that undeniably secured his lasting fame. These include the delineation of disseminated sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (known as “Charcot’s disease”), locomotor ataxia and its distinctive arthropathies (“Charcot’s joints”), his work on cerebral and medullar localizations, and aphasia.

On the other hand, objectively evaluating Charcot’s “third career” his exploration of hysteria and hypnotism is highly challenging. Like many scientists, he eventually lost control over the very ideas he had formulated and became consumed by the movement he had initiated. Pierre Janet accurately described Charcot’s methodological errors in this field. His first error was an excessive preoccupation with delineating specific disease entities, selecting cases that exhibited the maximum number of symptoms as model types, and assuming the remaining cases were incomplete forms

.Despite these flaws, Charcot’s work laid an early foundation for approaches now used in hypnosis therapy Dubai, where psychological and somatic conditions are explored through guided trance work. His influence is still echoed in the practices of the modern psychiatrist Dubai professionals who address complex psychosomatic conditions with a more integrated understanding.

In his later years, doubts plagued him, and he contemplated a return to the study of hypnotism and hysteria before his untimely death.

“Napoleon of Neuroses”

From 1870 to 1893, Charcot was considered the greatest neurologist of his time, consulted by royalty and patients from distant lands. The public perceived Charcot as a man who delved into the depths of the human mind, earning him the nickname “Napoleon of Neuroses.”

He gathered a dedicated team of the brightest physicians from different countries. Charcot’s disciples included prominent names such as Bourneville, Joffroy, Cotard, Gilles de la Tourette, Paul Richer, Pierre Marie, Raymond, and Babinski. Nearly every French neurologist of that era had studied under Charcot.

His lectures were meticulously recorded and published, and his influence extended to the Paris medical faculty. Charcot’s fame symbolized France’s scientific prowess, rivalling Germany’s alleged superiority.

The physician of kings and princes

Every Tuesday, Charcot hosted lavish receptions in his splendid home, attended by the crème de la crème of scientists, politicians, artists, and writers. He was known to have treated and even confided in kings and princes. Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, for instance, visited Charcot’s home, played billiards with him, and attended his lectures at the Salpetriere. Charcot wielded significant influence in English medical circles, as evidenced by the enthusiastic reception of his demonstration on tabetic arthropathies at an international congress in London in 1881.

Despite his popularity, he declined invitations to congresses in Germany after the Franco-Prussian war of 1870 to 1871. In Vienna, he had acquaintances in the likes of Theodor Meynert and Moritz Benedikt. Charcot enjoyed great popularity in Russia, where he was called upon multiple times to serve as a consultant physician to the czar and his family. Russian physicians welcomed him as he liberated them from their heavy reliance on German scientists. According to Guillain, Charcot orchestrated an unofficial meeting between Gambetta and the Grand Duke Nikolai of Russia, resulting in the Franco-Russian alliance.

Studies on hysteria

In 1878, influenced by Charles Richet, Charcot expanded his interest to hypnotism, scientifically studying it like he did with hysteria. Charcot, utilized his method for organic neurological diseases to investigate hysteria, providing a detailed description of the “grand hysterie” crisis.

Several gifted female hysterical patients became his subjects, progressing through stages of “lethargy,” “catalepsy,” and “somnambulism” with distinct symptoms.

Traumatic paralyses versus psychic paralyses

Among Charcot’s remarkable achievements were his investigations on traumatic paralyses in 1884 and 1885. During his time, paralyses were predominantly attributed to nervous system lesions caused by accidents, though the concept of “psychic paralyses” had been proposed in England by B.C. Brodie in 1837 and Russel Reynolds in 1869. However, how could a purely psychological factor induce paralysis without the patient’s awareness or the possibility of feigning?

Charcot used experimental studies to examine the disparities between organic and hysterical paralyses.

Experimental research

In 1884, three men with trauma-induced monoplegia of the arm were admitted to Salpêtrière. Charcot showcased that while these paralyses differed from organic ones, they precisely aligned with cases of hysteria. The next step involved experimentally reproducing similar paralyses under hypnotism.

Charcot suggested to hypnotized subjects that their arms would become paralyzed, resulting in hypnotic paralyses that mirrored spontaneous hysterical and posttraumatic cases. He meticulously replicated these effects and even suggested their reversal under controlled conditions. To demonstrate the role of trauma, Charcot selected easily hypnotizable individuals and suggested that their arms would be paralyzed upon receiving a slap on the back in their waking state.

These groundbreaking demonstrations not only advanced the understanding of hysteria, but also laid important groundwork for methods now examined and adapted by modern practitioners such as a neurologist Dubai specialist working at the intersection of trauma, psychology, and physical symptoms.

The subjects exhibited posthypnotic amnesia and instant monoplegia when slapped, identical to posttraumatic monoplegia. Additionally, Charcot observed that certain subjects in permanent somnambulism experienced arm paralysis without verbal suggestion after being slapped. This illustrated the mechanism of posttraumatic paralysis. Charcot deemed the nervous shock following trauma akin to a hypnotic state, enabling individual autosuggestion. Charcot concluded that his experimental research accurately depicted the condition he aimed to study. He classified hysterical, posttraumatic, and hypnotic paralyses as dynamic paralyses, distinct from organic paralyses caused by nervous system lesions.

In 1892, he distinguished “dynamic amnesia” with recoverable memories under hypnosis from “organic amnesia” where recovery was impossible. Towards the end of his life, Charcot recognized a vast realm between clear consciousness and organic brain physiology.

Introducing hysteria to academia

Charcot presented his findings to the Academie des Sciences in early 1882. It was an impressive feat, considering the Academie’s prior condemnation of hypnotism. It was possible due to Charcot’s scientific reputation as France leading neurologist. This groundbreaking scientific change of paradigm granted hypnotism newfound respect, prompting numerous publications on the once shunned subject.

Charcot. The magician

Despite his already immense prestige, Charcot was shrouded in an air of mystery, which gradually grew after 1870 and peaked with his renowned paper on hypnotism in 1882. He acquired a reputation as a great magician of sorts, with reports of quasi-miraculous cures attributed to him. One of his collaborators, Dr. Lyubimov recounts instances where patients, brought to Charcot from all over the world on stretchers or with complex apparatuses, were able to walk again upon his orders. He became closely associated with the discovery and interpretation of various neurological conditions, including hysteria, hypnotism, split personality, catalepsy, and somnambulism.

Curious tales circulated about Charcot’s influence over the hysterical young women of the Salpetriere and the intriguing events that took place there. During a patients’ ball, for example, the unintended sound of a gong caused many hysterical women to instantly fall into cataleptic states, maintaining the poses they were in when the gong sounded. Charcot’s piercing gaze was renowned for its ability to penetrate the depths of the past, retrospectively diagnosing neurological conditions in cripples depicted in artworks. He founded journals like the Iconographie de la Salpetriere and the Nouvelle Iconographie de la Salpetriere, pioneering the fusion of art and psychiatry.

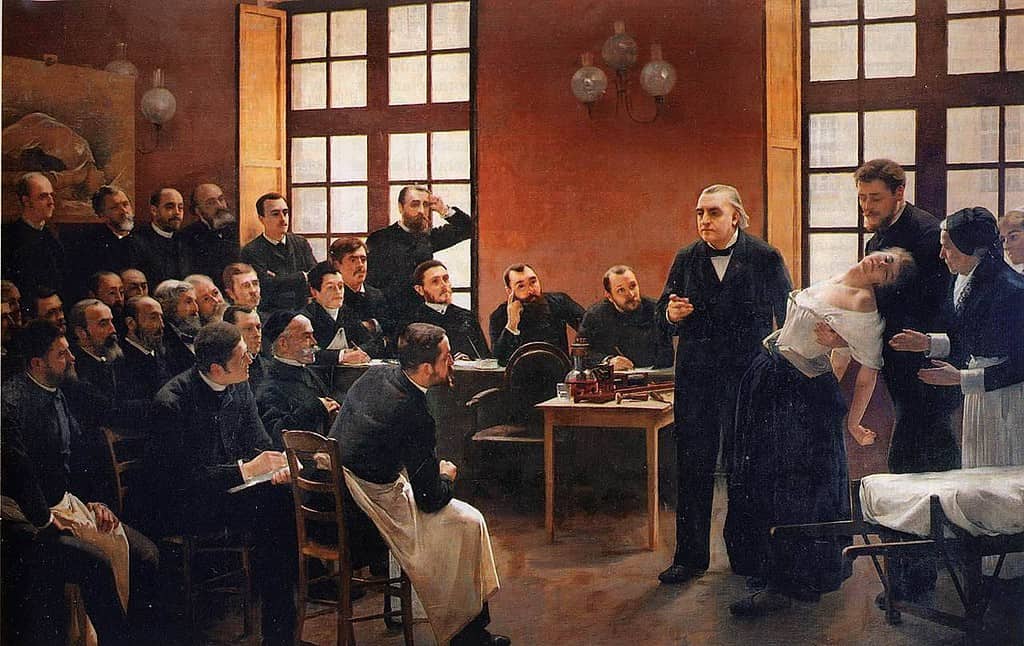

The lectures

Charcot’s séances at the Salpêtrière held an incomparable fascination, thanks to various captivating elements. The lecture hall filled to capacity with physicians, students, writers, and curious onlookers, awaiting Charcot’s entrance. Hysteria and hypnotism lectures were particularly spectacular.

Tuesday mornings were dedicated to examining new and unseen patients, delighting observers with Charcot’s clinical brilliance. His ability to unravel complex case histories and diagnose rare diseases swiftly impressed the audience.

However, the main attraction was his meticulously prepared and solemn lectures, held on Friday mornings. The auditorium would fill to capacity well before the lectures began, with a diverse audience of medical professionals, students, writers, and the curious. Adorned with relevant pictures and anatomical schemata, the podium awaited Charcot’s entrance at 10 a.m., often accompanied by esteemed foreign visitors and a group of assistants seated in the front rows.

The captivator

With a demeanour reminiscent of Napoleon, Charcot would take the stage, often accompanied by distinguished foreign visitors and assistants. He would begin speaking in a soft tone, gradually increasing his volume delivering concise explanations while skilfully illustrating them with coloured chalk drawings on the blackboard.

With a flair for drama, Charcot would mimic the behaviours, gestures, gait, and voice of patients with the discussed disease before their actual appearance. With adept coloured chalk drawings on the blackboard, he would provide clear explanations, vividly illustrating the behaviours, mannerisms, gait, and voice of patients afflicted with the discussed diseases.

Occasionally, the patients’ entrances were also dramatic. For instance, during lectures on tremors, women wearing hats adorned with long feathers would be introduced, their trembling feathers allowing the audience to discern the specific characteristics of tremors in different diseases. The interaction between Charcot and the patient took the form of a captivating dialogue.

Introducing modern style lecturing

Charcot also introduced the innovative use of photographic projections, a rarity in medical teaching at the time. The lectures concluded with a discussion of the diagnosis and a concise recapitulation of the main points. Lasting two hours, the lectures never felt too long, even when addressing rare organic brain diseases. Comparing Charcot’s lectures to those of Meynert, Lyubimov noted a striking difference. While Meynert’s lectures left him exhausted and confused, Charcot’s left him exhilarated.

The spellbinding effect of Charcot’s teaching extended to laymen, many physicians, and foreign visitors like Sigmund Freud, who spent several months at the Salpetriere. However, not all visitors were convinced. The Belgian physician Delboeuf, who arrived in Paris during the same period as Freud, became increasingly doubtful when he witnessed the careless experimentation with hysterical patients. He later published a strongly critical account of Charcot’s methods upon returning to Belgium.

Charcot. The man

Leon Daudet, who studied medicine at the Salpetriere, vividly described Charcot in his Memoirs. Charcot was a robust man with a prominent head, a bull-like neck, and a thoughtful expression on his low forehead and broad cheeks. Resembling Napoleon, he groomed his straight hair back and maintained a clean-shaven face.

Charcot possessed a heavy gait, an authoritative and somewhat low voice that often-carried irony, and an extraordinarily fiery expression. He was highly knowledgeable, well-versed in the works of Dante, Shakespeare, and other great poets, and he could read English, German, Spanish, and Italian. His extensive library housed a collection of peculiar and unique books. Despite his authoritarian nature, Charcot displayed deep compassion for animals, strictly forbidding any mention of hunters or hunting in his presence.

The authoritarian

One of his students described him as an authoritarian man, who could exert such a despotic control over those around him. His pulpit was a stage from which he cast sweeping and suspicious glances at his students, interrupting them with brief and imperative words. Contradiction, no matter how minor, was intolerable to him. If anyone dared to challenge his theories, he would become ferocious and mean, doing everything in his power to ruin the imprudent individual’s career unless they retracted and apologized. Additionally, he had no tolerance for stupidity.

However, his desire for domination led him to eliminate the more brilliant disciples, resulting in a circle of mediocre individuals surrounding him. As a compensatory measure, he maintained social connections with artists and poets, hosting splendid receptions.

The humanist

Remarkably, the description provided by the Russian physician Lyubimov differs so greatly that one could hardly believe it pertains to the same individual. Alongside his exceptional talent as a teacher, scientist, and artist, Charcot was incredibly humane and devoted to his patients. He would not tolerate any unkind remarks in his presence and maintained a poised and sensible demeanour. He possessed a keen eye for recognizing people’s worth and exercised caution in his judgments.

Charcot enjoyed a harmonious and happy family life. His wife, who became his partner after being widowed with a daughter, actively supported his work and engaged in charitable endeavours. He invested great care in the education of his son Jean, who willingly chose to become a physician and brought immense joy to his father with his initial scientific publications.

Charcot garnered devotion from both his students and patients, resulting in celebrations and jubilation on his patron saint’s day, Saint Martin, at the Salpetriere on November 11th.

The criticism

The extreme opinions and fascination surrounding Charcot, combined with the intense enmities he garnered, hindered a true assessment of the value of his work during his lifetime. Even with the passage of time, this task remains challenging. Hence, it is necessary to distinguish the various fields of his activity. Without any doubt Charcot occupies a prominent place in the panteon of internal medicine and neurology, to which he contributed as an internist and anatomo-pathologist, particularly in pulmonary and kidney diseases, and as neurologist, describing disseminated sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Charcot’s disease), locomotor ataxia, cerebral and medullary localizations, and aphasia.

Disputes about studies on hysteria

However, evaluating objectively his exploration of hysteria and hypnotism, considered his “third career,” proves challenging. Charcot lost control of the ideas he had formulated, succumbing to the movement he had initiated, as accurately noted by Pierre Janet.

The errors

The first misassumption was Charcot’s excessive focus on delineating specific disease entities and selecting extreme cases as model types, neglecting incomplete forms.

Considering his method’s success in neurology, he assumed it would apply to mental conditions as well. He provided arbitrary descriptions of “grande hysterie” and “grand hypnotisme.” Simplifying these descriptions to aid student comprehension was his second error.

The third fatal error was Charcot’s lack of interest in his patients’ backgrounds and the Salpetriere’s ward life. He rarely made rounds; instead, his collaborators examined the patients and reported to him. Unbeknownst to Charcot, incompetent individuals often visited and magnetized his patients on the wards. Janet demonstrated that the alleged “three stages of hypnosis” were merely the result of training by magnetizers.

Furthermore, Janet emphasized that Charcot’s descriptions of hysteria and hypnotism were based on a limited number of patients.

Towards the end of his life even Charcot himself became doubtful contemplating his study of hypnotism and hysteria, but death intervened.

The mutual suggestions

Another distortion was the collective spirit prevalent in the Salpetriere – a closed community housing not only elderly women but also special wards for young, attractive, and cunning hysterical patients. This environment fostered mental contagion, ideal for demonstrations to students and Charcot’s lectures attended by “Tout-Paris”.

Due to Charcot’s paternalistic attitude and despotic treatment of students, his staff dared not contradict him. They presented what they believed he wanted to see after rehearsing demonstrations, even discussing cases in front of patients. This created an atmosphere of mutual suggestion among Charcot, his collaborators, and patients, warranting a thorough sociological analysis.

Six years after Charcot’s death, a few of his hysterical female patients at the Salpetriere would perform complete attacks of “grande hysterie” for a small fee, entertaining the students. However, over time, hysterical patients disappeared from the Salpetriere.

The enemies and the traitors

Laymen, physicians, and foreign visitors like Sigmund Freud were captivated by Charcot’s teaching but remained unaware of the powerful enemies surrounding him.

The church and the magnetists

The clergy and Catholics branded him an atheist, partly due to his replacement of nuns with lay nurses at the Salpetriere. However, even some atheists found him too spiritual. Magnetists publicly accused him of charlatanism, while political and societal circles harboured fierce animosity towards him, as documented in the Goncourt brothers’ Diary.

Battle with the Nancy School

Charcot faced an ongoing battle against the Nancy School, gradually losing ground to his opponents. Bernheim sarcastically proclaimed that among the thousands of patients he hypnotized, only one displayed the three stages described by Charcot—a woman who had spent three years at the Salpetriere. Charcot also faced intense hatred from some of his medical colleagues, particularly his former disciple Bouchard, a man twelve years his junior.

Charcot and neurologists

Among neurologists, some who admired Charcot while he focused on neuropathology deserted him when he delved into the study of hypnotism and conducted dramatic experiments with hysterical patients. After visiting Charcot in Paris, the German neurologist Westphal expressed deep concerns about the new direction of Charcot’s research. In America, Bucknill attacked Charcot on similar grounds. However, Beard (who coined the term “Neurastenia”), while acknowledging Charcot’s serious mistakes, still respected him as a genius and a man of honor.

Departure of disciples

Furthermore, a few seemingly loyal disciples deceived Charcot by orchestrating extraordinary manifestations with patients and demonstrating them to him. Although many of his disciples were not involved in such activities, no one dared to warn him. Initially cautious, Charcot eventually fell victim to the truth of La Rochefoucauld’s maxim: “Deception always goes further than suspicion.”

Joseph Babinski, one of Charcot’s favoured disciples, became the leading figure in a radical reaction against Charcot’s concept of hysteria. He claimed that hysteria was simply the result of suggestion and could be cured through “persuasion.”

His successor, Raymond, paid homage to Charcot’s work on neuroses but aligned himself with the organicist trend in neurology.

The king is death

The actions of men persist long after they’re gone; their good deeds often forgotten and buried. Such was the fate of Charcot. Soon after his death, his glory transformed into the image of a despotic scientist whose arrogance blinded him to the unleashing of a psychological epidemic. In less than a decade after his death, Charcot was largely forgotten and disavowed by his disciples. During Charcot’s final months, the old man expressed himself pessimism about the future of his work, fearing it would not endure.

After his death, Leon Daudet, a former medical student on Charcot’s ward, published a satirical novel called Les Morticoles. It mockingly portrayed prominent physicians of the Paris medical world. The novel included exaggerated depictions of fake hypnotic sessions with a character resembling one of Charcots patients, Blanche Wittmann. Axel Munthe, in his autobiographical novel The Story of San Michele, also presented a malevolent account of Charcot’s Salpetriere.

Charcot, forgetting the early history of magnetism and hypnotism, believed he made new discoveries in his hypnotized patients, more so than Bernheim.

Charcot’s late rehabilitation

Charcot’s neurological discoveries became accepted and his name became associated with a regrettable episode in the Salpetriere’s long history. In 1925, his centennial was celebrated at the Salpetriere, emphasizing his neurological achievements and offering some apologies for the slight shortcomings in his work on hysteria and hypnosis.

In 1928, a group of Paris surrealists sought to challenge conventional ideas and celebrated Charcot’s discovery of hysteria as “the greatest poetical discovery of the end of the nineteenth century.”

Psychoanalysts praised him as a precursor to Freud in that regard. Predeceasing Freud one of Charcot’s favourite notions was that the role of dreams in our waking life was not just immense but far more significant than commonly believed.

Despite Charcot’s misinterpretation of hypnotic phenomena, actually it was his study on hysteria which immortalized his name.