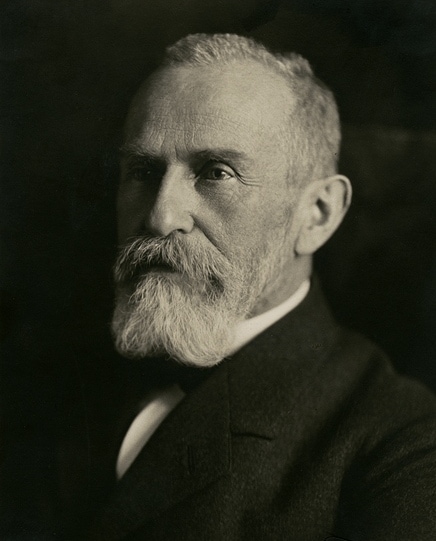

Paul Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) was a Swiss psychiatrist and Medical Director of the Psychiatric Hospital Burghölzli in Zurich, famous for his contribution in the development of psychiatry and psychoanalysis. He gained worldwide recognition for introducing the terms schizophrenia, autism, and ambivalence.

Bleuler redefined the term dementia praecox, originally described by Emil Kraepelin, refining its diagnostics and coining the condition’s new term schizophrenia. In his definition, he incorporated psychological and, to a lesser degree, social factors into the assumed neurobiological mechanism underlying the disorder. This re-evaluation of dementia praecox positioned him as an early advocate of the bio-psycho-social model of mental illness.

Eugen Bleuler. Personal Life

On April 30, 1857, Paul Eugen Bleuler was born in Zollikon, a current suburb of Zurich. He was the second-born child of Hans Rudolf Bleuler, a silk merchant and farmer, and his wife Pauline. Paul grew up in a rural setting with his five-year older sister, Anna Pauline (1852–1926).

Bleuler’s interest in psychiatry is thought to originate from his sister Anna, who has suffered from a serious mental disorder since early adulthood. Her symptoms had been described as “chronified catatonic mutism.” Unfortunately, the absence of clinical records in the archives leaves much unknown about her early and later years.

In 1901, Bleuler married Hedwig Bleuler-Waser, who was one of the first women to obtain her doctorate from the University of Zurich. They met while campaigning for the abstinence movement, which promoted moderation or complete abstinence from alcohol. Hedwig later founded the Swiss Federation of Abstinent Women. The founding of this federation was suggested to her by Auguste Forel, a Swiss psychiatrist, neuroanatomist, and eugenicist.

Bleuler and his wife had five children together, and Hedwig organized social gatherings at the psychiatric hospital where her husband worked, including afternoon teas.

Eugen Bleuler’s Professional Career

Bleuler studied medicine at the University of Zurich, graduating in 1881. Thereafter, he obtained his doctorate while working as a medical assistant at the Waldau Hospital in Bern. In 1884, he left his post and embarked on a year-long study trip. He visited Salpetiere Hospital in Paris, participating in Jean-Martin Charcot lectures.

Upon returning to Switzerland, he briefly worked as an assistant to Auguste Forel at the University Hospital of Psychiatry in Zurich, known as “Burghölzli.” Forel was known for his contributions to hypnosis that influenced the development of psychoanalysis by Sigmund Freud.

He became the director of the Rheinau Psychiatric Hospital at the young age of 29. Twelve years later, he succeeded Auguste Forel as director and professor of psychiatry at Burghölzli Hospital. He occupied this chair until his retirement in 1927. His son, Manfred Bleuler, later took over the clinic and became a professor of psychiatry, following in his father’s footsteps. The life and work of Eugen Bleuler Psychiatrist biography remain influential, and his pioneering research on eugen bleuler schizophrenia continues to shape modern psychiatric studies.

The partnership with Freud inspired Bleuler to integrate psychoanalysis into his clinical practice later in his career.

Eugen Bleuler and Carl Gustav Jung

In 1900, Bleuler supervised Carl Gustav Jung’s dissertation titled On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena. In 1905, Jung had become Bleuler’s senior physician. Jung carried out the famous Word Association Experiment, providing the first scientific proof for Freud’s psychoanalytical theory. Bleuler, along with Jung and other psychiatrists working in Burghölzli, created an important research group within the psychoanalytic movement. Besides Jung, who is renowned for his contributions to psychology, many of Bleuler’s students later achieved the title of professor themselves, such as Hans Steck, Max Müller, and Jakob Kläsi. Within these circles, social life was characterized by extensive professional exchange alongside strict moral norms, including a ban on alcohol consumption. Bleuler considered his contributions to the treatment of alcoholism as one of his most significant works.

Eugen Bleuler and Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud, an almost exact contemporary of Bleuler, lived from 1855 until 1939. The relationship between Eugen Bleuler and Sigmund Freud has been described as ambivalent. Although Bleuler was the first to introduce Freud’s psychoanalysis to a hospital environment, contributing to its academic recognition, he disagreed with Freud’s concepts. These included the meaning of libido and the relationship between psychological phenomena and sexuality. Due to a lack of scientific proof, Bleuler found these concepts too premature to accept.

Dementia Praecox

Bleuler redefined Emil Kraepelin’s clinical definition of dementia praecox as schizophrenia. Bleuler recognized the difference between dementia, an organic brain damage, and schizophrenia, a distinct psychiatric condition. In 1908 he published “Dementia Praecox: Or the Group of Schizophrenias.”

Bleuler stated that

“The schizophrenic is not simply demented, but merely demented with respect to certain questions, at certain times, and in response to certain complexes.”

Bleuler, 1911, pp. 452-453

He emphasized the existence and importance of distinguishing between primary and secondary symptoms, which remain relevant today.

The disease mechanism describes primary symptoms as integral. The secondary symptoms are defined as responses to the affected psychic interaction with the external and internal worlds. Furthermore, he observed that schizophrenic patients with acute symptoms have a better prognosis than those with less severe but long-lasting symptoms. His work also influenced notable figures such as eugen bleuler c.g.jung and eugen bleuler sigmund freud, shaping early psychoanalytic and psychiatric theories.

Coining Term: Schizophrenia

Bleuler coined the term schizophrenia from the Greek words “schizein,” meaning splitting, and “phren,” originally signifying “diaphragm” but symbolizing the “soul, spirit, mind;” in Ancient Greece, the diaphragm was believed to be the house of the mind.

Bleuler chose this name because he believed that the minds of schizophrenics were temporarily dominated by one complex, while other functions were “split off,” leaving them partially or wholly ineffective.

Contrary to common modern assumptions, the term does not imply a splitting of personalities. According to Bleuler, schizophrenia represents a group of disorders with shared symptoms but also significant variation in symptoms. He differentiated between basic and accessory symptoms, as well as between primary and secondary symptoms. Bleuler referred to basic symptoms as those that must be present in any form of schizophrenia, whereas accessory symptoms may or may not occur.

The distinction between primary and secondary symptoms is related to the aetiology and pathogenesis of the disorder. Primary symptoms are directly caused by the assumed neurobiological disease process, while secondary symptoms are defined as the psyche’s response to the primary symptoms.

Bleuler identified four primary symptoms, also known as the four A’s: abnormal association, autism, abnormal mood, and ambivalence. He coined the term “ambivalence,” defined as the presence of conflicting emotions, and “autism,” referring to the tendency of patients to withdraw into an “inner world” of their own making.

Bleuler classified the symptom of abnormal association as both a basic and primary symptom, indicating its central role in his conception of schizophrenia.

Eugen Bleuler and Eugenics

While Bleuler’s contribution to the field of psychiatry is admirable, his actions regarding eugenics have been critically reappraised. Like his predecessor Auguste Forel, Bleuler supported the eugenics movement and advocated for the sterilization of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. He believed that the reproduction of “the mental and physical cripples” would result in racial deterioration.

During the early 20th century, the “racial hygiene” policies of Nazi Germany were widespread worldwide. This led to multiple eugenically motivated attempts to restrict the reproductive rights of patients and people with disabilities, including forced sterilization and even the euthanasia of patients. Burghölzli, under Bleuler’s supervision, produced reports supporting surgical interventions on eugenic grounds.

The clinic continued to perform sterilizations also under the direction of Bleuler’s son, Manfred. In 1928, the Swiss canton of Vaud introduced Europe’s first law legalizing non-consensual sterilization. Bleuler commented that “mad doctors” were “utterly wrong” for approving the procreation of mentally defective and inferior persons. He contended that experts had a “legitimate duty” to assess serious cases and decide on the appropriateness of euthanasia. Eugenic sterilization practices continued in Switzerland until the 1970s.

Eugen Bleuler. Summary

In summary, Paul Eugen Bleuler’s contributions to the field of psychiatry have left an enduring mark on our understanding of mental illness. His introduction of the terms schizophrenia, autism, and ambivalence has shaped the discourse in psychiatry for generations. Furthermore, his advocacy for a biopsychosocial approach to mental illness is still relevant today.

Bleuler’s personal and professional life were characterized by significant achievements. He created a flourishing scientific circle contributing to the development of psychiatry and psychology, especially to the development of psychoanalysis. Bleuler helped develop a successful scientific career for several of his subordinate doctors, among them Carl Gustav Jung.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the controversial aspects of Bleuler’s legacy. His promotion of eugenics, along with the eugenic sterilization of individuals, remains a subject of critical debate and ethical reflection.

In evaluating Bleuler’s legacy, we must recognize both his substantial contributions to psychiatry and the complexities surrounding his views on eugenics. His work has impacted the field immensely, and his legacy continues to shape our understanding of mental illness and treatment.

Sources

Arantes-Gonçalves F, Gama Marques J, Telles-Correia D. Bleuler’s Psychopathological Perspective on Schizophrenia Delusions: Towards New Tools in Psychotherapy Treatment. Front Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 17;9:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00306. PMID: 30065668; PMCID: PMC6056670.

Sass, L. A. (1994). Civilized madness: schizophrenia, self-consciousness, and the modern mind. History of the Human Sciences, 7(2), 83-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/095269519400700206.

Ashok AH, Baugh J, Yeragani VK. Paul Eugen Bleuler and the origin of the term schizophrenia (SCHIZOPRENIEGRUPPE). Indian J Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;54(1):95-6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.94660. PMID: 22556451; PMCID: PMC3339235.

Bleuler, E. (1911). Dementia praecox, oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien (Vol. 4). Deuticke.

Brückner, Burkhart. Biographical entry: Anna Pauline Bleuler (1852-1926). 2015/11/19.

Maatz A, Hoff P, Angst J. Eugen Bleuler’s schizophrenia–a modern perspective. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015 Mar;17(1):43-9. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.1/amaatz. PMID: 25987862; PMCID: PMC4421899.

Moskowitz A, Heim G. Eugen Bleuler’s Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias (1911): a centenary appreciation and reconsideration. Schizophr Bull. 2011 May;37(3):471-9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr016. PMID: 21505113; PMCID: PMC3080676.