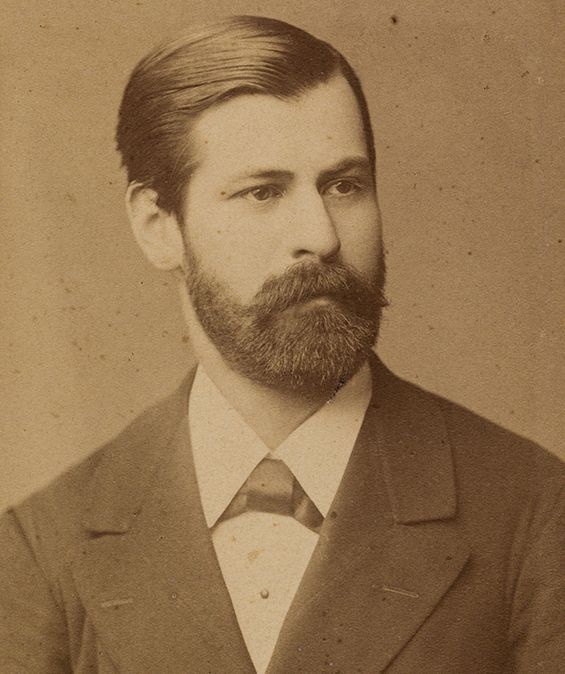

Cocaine was extracted from coca leaves in 1860 by the German chemist Albert Niemann. At the beginning of 1884, Sigmund Freud heard about a German Army doctor, Theodor Aschenbrandt’s, success using cocaine to boost soldiers’ endurance. The same year, Freud and Karl Koller had been experimenting with cocaine at the Vienna General Hospital.

Freud believed cocaine was a safe substance and useful for treating symptoms of fatigue and nervous exhaustion. In July 1884, Freud found out about the anesthetic effect of cocaine on a dog’s eye.

During Freud’s absence, Koller had secretly conducted similar experiments and, on September 15, 1884, presented his findings at the Ophthalmological Congress in Heidelberg.

Koller’s discovery caused a sensation, and he quickly gained fame for revolutionizing eye surgery. For the first time, pain-free operations such as those for glaucoma were made possible by applying a cocaine solution.

This article sheds light on the controversial aspects of Sigmund Freud’s research on cocaine and the complications caused by its use.

Freud’s Research on Cocaine

Taking small doses of cocaine, Freud found it relieved his depression, helped him focus, and seemed harmless. This triggered his interest in cocaine, a possible remedy for various diseases.

Sigmund Freud was the first German-speaking scientific author and writer to discuss cocaine. In 1884, he wrote the first comprehensive German-language monograph under the title On Coca. The monograph primarily consisted of reproductions from American literature, but Freud also incorporated several personal observations. Some of them came from Freud’s own experiments, which later became linked to early Freudian theories about the psyche.

From 1884 to 1887, Freud wrote a total of four articles on cocaine. In all of them, he advocated for its medical use. However, Freud gradually withdrew his recommendation to use cocaine for treating alcoholism and morphinism. The concept finally fully disappeared in his last essays, due to strong criticism from the professional community.

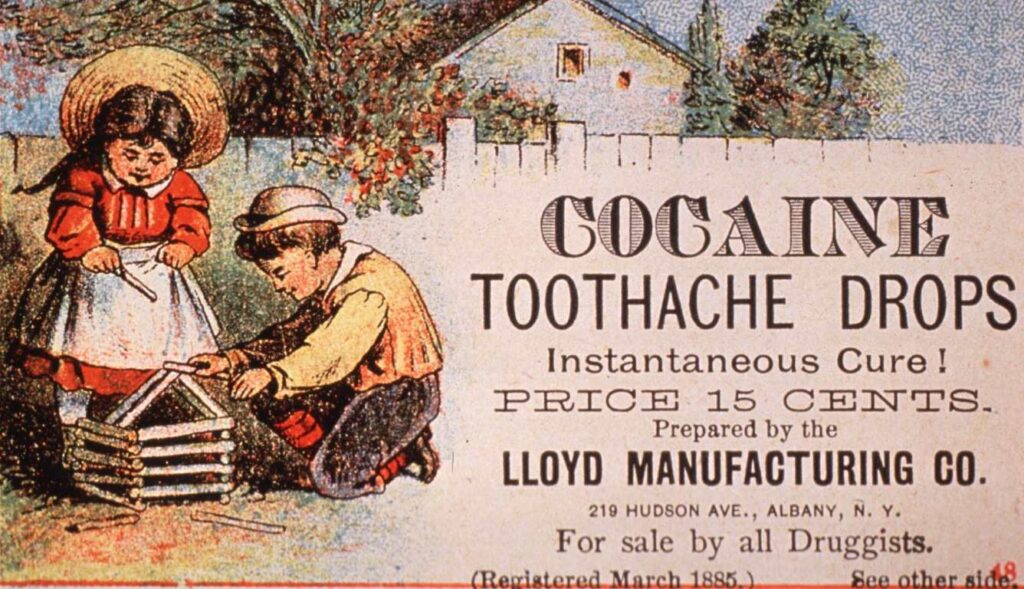

Societal Context of Cocaine Use in the Late 19th Century

When assessing Freud’s cocaine use, one must consider the societal context of the late 19th century. At the end of the 19th century, cocaine just appeared in Europe and the US. Initially, its use was not prohibited; on the contrary, there was a euphoric attitude towards its perceived positive effects.

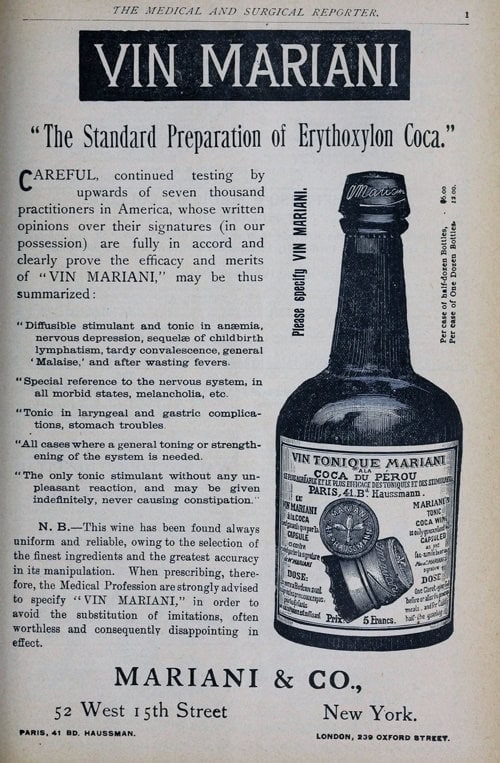

Socially integrated cocaine consumption primarily took the form of cocaine-containing preparations. The most famous of these was “Vin Mariani.” Angelo Mariani, a Parisian pharmacist, introduced this product in 1877, triggering a trend.

The original form of Coca-Cola, a syrup diluted in soda water, was introduced by Pemberton in 1886. A contemporary report in the “Detroit Therapeutic Gazette” from 1881 indicates that other forms of consumption had also become popular.

In the late 19th century, the use of “coca wine” was widespread. The beverages containing cocaine were used by artists, scientists and politicians, among them such personalities as Pope Leo XIII, U.S. President McKinley, Thomas Alva Edison, Henrik Ibsen, Jules Verne, Émile Zola, Rodin, etc.

Freud’s Promotion of Cocaine

Freud’s early fascination with cocaine led him to champion its use for various psychological and nervous conditions. One of its main indications was the treatment of alcohol and morphine addiction. Based on his experiences, Freud initially regarded cocaine as non-addictive and harmless. His self-trials led him to describe the drug as “magical,” increasing self-control, vitality, and capacity for work.

Freud regularly took small doses to combat his depression, recommending it widely—even to his family and fiancée, Martha Bernays. On June 2, 1884, Freud wrote a love letter to his fiancée, Martha Bernay, describing his experience with the drug:

“Woe to you, my princess, when I come. I will kiss you quite red and feed you till you are plump. And if you are forward, you shall see who is stronger, a gentle little girl who doesn’t eat enough or a big wild man who has cocaine in his body.”

And on other occasions:

“In my last depression, I took Coca again, and a small dose lifted me to the heights in a wonderful fashion. I am just now busy collecting the literature for a song of praise to the magical substance.”

The Case of Fleischl-Marxow

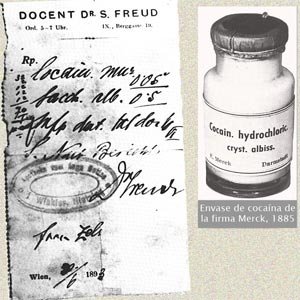

In spring 1884, Freud purchased a gram of cocaine from Merck at significant expense, as he noted. He conducted self-experiments with part of this sample, passing another part to his paternal friend Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow.

Fleischl started to use morphine as a painkiller for phantom pain after injuring and amputation of his thumb.

Freud’s attempts to wean Fleischl off morphine by using cocaine showed initial promise. The first recommendation for cocaine as a withdrawal agent for morphinism was described in Canadian and American literature.

However, Fleischl soon increased his cocaine dose to more than a gram per day and became a cocaine-morphinist. Instead of healing, he fell even deeper into the abyss of addiction and eventually died in 1891.

Although Fleischl’s condition was likely no worse than his prior morphine addiction, his tragic fate haunted Freud as a reminder of his premature endorsement of cocaine.

Criticism on Freud

The German psychiatrist Friedrich Erlenmayer accused Freud of contributing to the spread of cocaine use. Erlenmayer described the use of cocaine as a third scourge on humanity after alcohol and morphine. However, Freud did not initiate any of the application areas of cocaine; he just described them. Furthermore, he was convinced of the need for further studies to confirm the favorable reports he mentioned. In this sense, he was by no means a promoter of cocaine use.

Also, the unfortunate treatment of his friend Fleischl made Freud sceptical about the use of cocaine as medication. Over time, he gained awareness of cocaine’s addictive nature, as evidenced by a later statement:

“In my naïveté at the time, I had not considered that cocaine could do nothing against the pains that drove Fleischl to constant use of morphine. After a surprisingly simple weaning from morphine, he became a cocaine user instead of being a morphinist.”

Freud and Cocaine Dependence

The available information about Freud’s cocaine use excludes the hypothesis of Freud’s addiction. Freud didn’t use cocaine excessively over a long period of time, which would be necessary to create cocaine dependence. The drug also didn’t have any impact on Freud’s thinking as a researcher.

While experimenting on cocaine, Freud authored neurological works that were well-received in the professional community. In 1891, he published a book on aphasia and several essays on pediatric disorders and became a leading authority in these fields.

In letters to his friend Wilhelm Fliess, Freud appears as a vibrant thinker, logically developing his ideas and arriving at understandable conclusions. His writing is not showing any signs of scattered thoughts. Furthermore, these letters reveal Freud’s engagement with family and friends. Freud also extensively discussed his health issues with Fliess, who was his consulting physician, and there is no evidence of cocaine addiction.

Freud’s Awareness of Dependencies

Freud’s publications indicate that he was aware of the problem of dependencies with a nuanced view on the potential habit-forming drug effects. In 1887, he confronted Erlenmayer with “critical remarks on cocaine fear.” At that time, he noted that he had extensive experience with long-term controlled cocaine use by others who were not morphinists and that he himself had not felt dependent when he used cocaine for several months. In 1896, he wrote:

“The same applies to all other abstinence cures, which will only appear to succeed as long as the physician is content to withdraw the narcotic from the patient without addressing the source from which the imperative need for such arises. Habituation is merely a colloquialism without explanatory value; not everyone who has the opportunity to take morphine, cocaine, chloral hydrate, etc. for a while will develop an addiction to these substances.”

Cocaine in Psychoanalysis

Despite the use of cocaine in psychiatry in the late 19th century, there are no indications that it was employed in the psychoanalysis. The reason is obvious: the psychoanalysis was developed and used after the medical stance on cocaine had already shifted into disrepute.

During that period, when certain psychoanalysts contemplated the possibility of accelerating the analytical process through drugs, there was never consideration of using cocaine for this purpose.

Cocaine in “Wild” Psychoanalysis

Otto Gross, the enfant terrible of psychoanalysis and the promoter of anarchism and liberated sexuality, was addicted to morphine and cocaine. He was the only significant figure in the history of psychoanalysis who used drugs in his pseudo-therapeutic interventions. During his career as a naval doctor, Gross got addicted to morphine and later became a cocaine morphinist. At the beginning of Gross’s career, Freud highly valued the young colleague for his innovative approaches towards psychoanalysis. Freud’s esteem went so far that he wrote to Carl Gustav Jung that aside from Jung himself, only Gross was capable of contributing something original to the psychoanalysts.

Later, Freud got aware of Grosse’s addiction. He made critical remarks about certain stylistic features in his writings, indicating the influence of cocaine. As Gross’s problems became more pronounced, Freud recognized in him a cocaine psychosis and sent him for therapy to Burghölzli Hospital in Zurich. Gross was treated by Jung, but at the end he escaped from the hospital and continued a nomadic life among the European bohème and anarchists.

The Legend of Cocaine’s Influence on the Development of Psychoanalysis

The cocaine episode in Freud’s life did not have the influence on psychoanalysis that has been attributed to it. During the time of his initial cocaine experiments, Freud was still far from developing the theory and practice of psychoanalysis.

The methodological weakness of Freud’s criticism based on the cocaine episode lies in its abandonment of any genuinely historical research and devolves into sensationalist journalism.

Freud’s Studies on Cocaine. Summary

Cocaine was first extracted from the coca plant in the mid-19th century. By the 1880s, the drug was still unregulated and a subject of intense research into its potential therapeutic benefits. In Europe and the US, liquids containing cocaine, such as “Vine Mariani,” were legal and used for the treatment of distinct illnesses.

During this period, Sigmund Freud began experimenting with cocaine. He published papers about its advantages based on American and Canadian literature and his personal experiences.

Apart from the unfortunate case of his friend Fleischl-Marxow, to whom Freud recommended the use of cocaine to heal his morphine addiction, there is no evidence that Freud was widely using the drug in clinical practice. With growing awareness of the drug’s detrimental effects, Freud distanced himself from the medical use of cocaine.

The cocaine episode remains a bittersweet chapter in Freud’s life. It brought him close to world fame at 28 but also tarnished his medical reputation.

Significance of Freud’s Studies on Cocaine

The true significance of Freud’s thoughts on cocaine, however, is overlooked. At the end of the 19th century there was no proper medication for the treatment of psychiatric illnesses. The only drugs used in psychiatry were the highly addictive morphine and chloralhydrate. They gave the patients a temporary relief, but by longer use they led to addiction. While using cocaine himself, Freud recognized its positive effect on his depression. Based on this experience, he suggested that psychiatry urgently needed psychiatric medication with stimulating properties. Such statements make him a precursor of modern psychopharmacology of depression.

It makes no sense to doubt Freud’s Nobel motivation leading him to the studies on cocaine and to pathologize Freud’s behaviour posthumously. Nor does it make sense to use the cocaine consumption of the creator of psychoanalysis as a tool for criticism against his scientific framework.

Sources

Freud S. Ueber Coca. Centralbl Ges Ther, 1884, 2, 289-314

Karch S.B. A brief history of cocaine. Boca Ration: CRC/Taylor & Francis, 2006

Freud, Biologist of the Mind. Beyond the Psychoanalytic Legend. Harvard University press. ISBN 9780674323353

Sigmund Freud, “The Cocaine Papers,” a personal appraisal, April 2001. International Journal of Drug Policy

Pendergrast M. For god, country, and Coca-Cola: the definitive history of the great American soft drink and the company that makes it. New York: Basic Books, 2000