Differnces between Freudian and Jungian psychology mirrors not only Freud’s and Jung’s conflicting scientific views but also their oposing personalities.

Freud believed in the doctrine of empiricism treating the psyche of a newborn as “tabula rasa” (blank slate), waiting for a content.

Jung never disagreed with Freud’s view that personal experience is of crucial significance for the development of each individual. However, he denied that this development occurred in an unstructured personality. For Jung, the role of personal experience was to develop what is already there – to activate the archetypal potential already present in the collective unconscious.

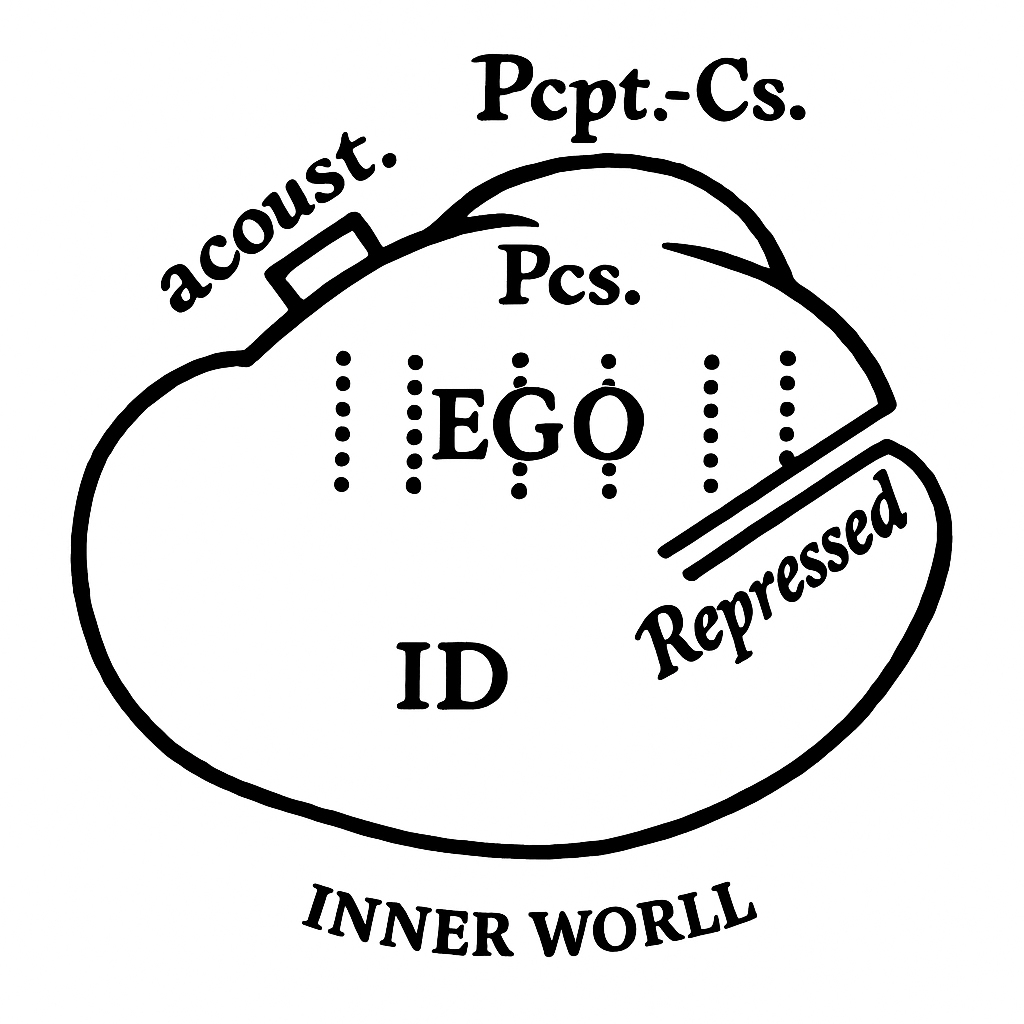

Freudian Model

Sigmund Freud proposed that human personality consists of three elements: the id, the ego, and the superego. These components interact to shape human behaviour.

The Id

The id is the source of all psychic energy and the primary component of personality, present from birth. It is entirely unconscious and includes instinctive and primitive behaviours. Driven by the pleasure principle, the id seeks immediate gratification of all desires, wants, and needs. In early life, the id is crucial because it ensures that an infant’s needs are met. Infants, ruled entirely by the id, cry until their needs are satisfied.

The Ego

The ego develops from the id and ensures that the id’s impulses can be expressed in a socially acceptable manner. It operates in the conscious, preconscious, and unconscious mind, dealing with reality. The term “ego” often describes the cohesive awareness of someone’s personality, but it is only one part of the full personality.

The ego operates on the reality principle, striving to satisfy the id’s desires in realistic and socially appropriate ways, weighing the costs and benefits of actions before deciding whether to act on or abandon impulses.

Freud compared the id to a horse and the ego to the horse’s rider. The horse provides power and motion, while the rider directs and guides it. Without the rider, the horse would wander aimlessly. Similarly, the ego directs the id’s impulses. The ego also manages tension created by unmet impulses finding real-world solutions to satisfy the id’s desires.

The Superego

The superego, the last component of personality to develop, emerges around age five. It holds internalized moral standards and ideals acquired from parents and society, forming our sense of right and wrong.

The superego provides guidelines for making judgments and has two parts: the conscience and the ego ideal. The conscience part contains information about behaviours viewed by the society as good and the others as not acceptable.

The ego ideal includes the rules and standards for behaviours the ego aspires to. The superego strives to perfect and civilize behaviour, suppressing the id’s unacceptable urges and pushing the ego to act on idealistic rather than realistic principles.

These three elements—id, ego, and superego—work together to form a complex human personality.

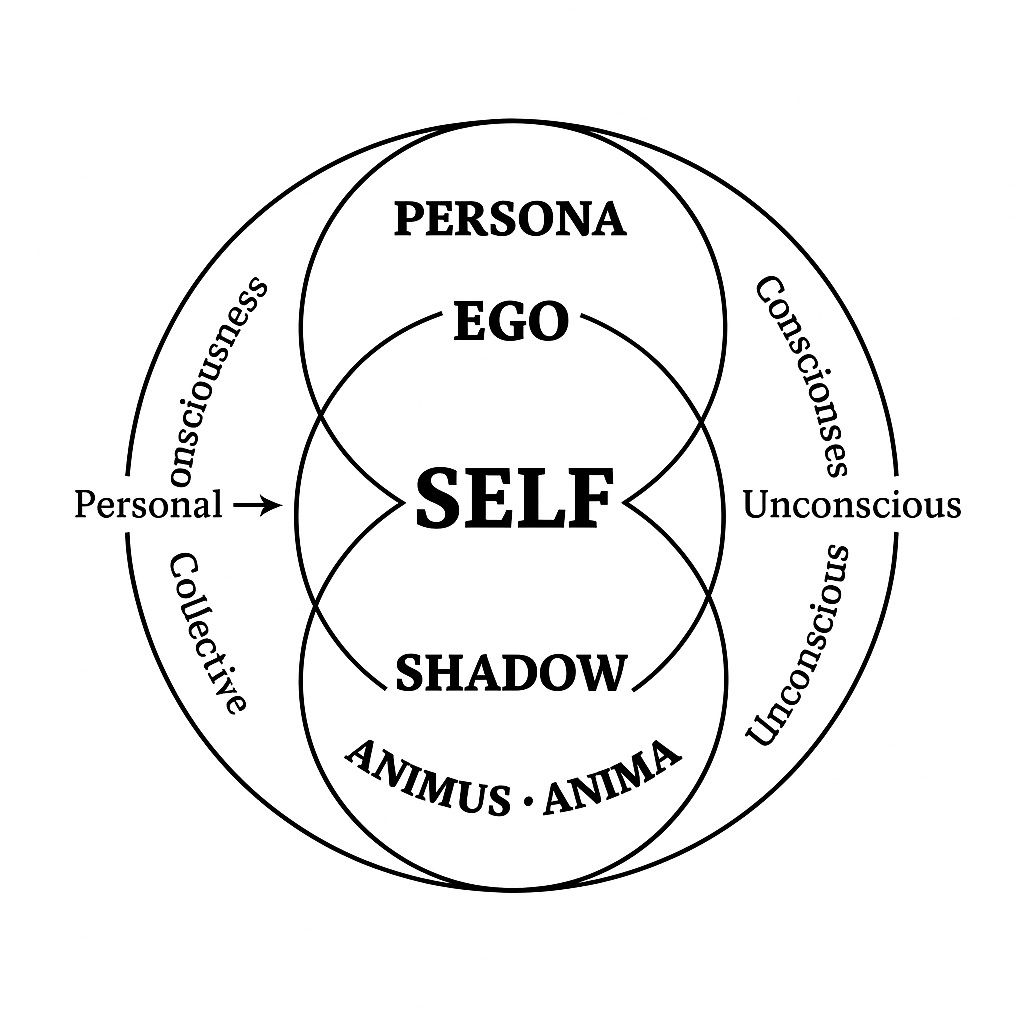

Jungian Model of the Psyche

A model of Jung’s psychology can be visualized as a globe or a sphere.

The Self

At the centre, and permeating the entire system with its influence, is the Self.

Collective Unconscious

In the lower part of the concentric circles is the collective unconscious, composed of archetypes such as anima, animus and the shadow.

Consciousness

The upper part of the second circle represents consciousness, with its focal ego orbiting the system rather like a planet orbiting the sun, or the moon orbiting the earth.

Personal Unconscious

Intermediate between the consciousness and the collective unconscious is the personal unconscious, which consists of complexes, each of which linked to an archetype. These complexes are personifications of archetypes; they are the means through which archetypes manifest them in the personal psyche.

Jung’s Concept of Libido

Jung found these and other aspects of Freud’s thinking reductionist and too narrow. Instead of conceiving psychic energy (or libido as Freud called it) as wholly sexual, Jung preferred to think of it as a more generalized “life force”, of which sexuality was but one mode of expression.

In work, and in a series of lectures given in New York in September 1912, Jung spelt out the “heretical” view that libido was a much wider concept than Freud allowed. He presented series of examples that this “life force” appears “crystallized” as the universal symbols apparent in the myths of humanity.

Jung’s publication of “The Symbols” initiated the final deprture from Freud.

Jung’s Departure from Freud

The incompatibility of their theoretical positions eventually led to mutual accusations, polemics, and disparagement, leading to the final abandonment of their relationship in 1913. In the same year Jung coined the term “Analytical Psychology“, to describe his own depth psychology school. This term refers both to practical therapeutic work and to signify the departure from Freudian psychoanalysis towards his own school of complex psychology.

Freud accused Jung of a lack of appreciation for scientific teaching, criticizing his style as confused, inconsistent, and ambiguous. Jung, on the other hand, criticized his former mentor, claiming that Freud’s intellectual grasp of the psychological process is paradoxical and dogmatic.

Freud’s and Jung’s Theoretical Differences

Freud derived his experiential material mainly from neurotics, whose conditions allowed for a more precise description of psychological processes.

Jung, on the other hand, gathered his experiential material primarily from psychotics during his work at Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital. The symptom of psychotic patients, in the form of hallucinations and delusions, are less differentiated and more confusing. Jung’s own childhood experiences and the data he gathered from psychotic patients led him to the assumption of universally shared unconscious contents. He found such themes not only in psychotics but also in the religions and myths of the world. Consequently, Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, archetypes and individuation was shaped more by a humanistic approach than by a causal-scientific model.

The End of the Friendship

The conflict between Jung and Freud became so hostile that the idea of combining their theories of depth psychology or psychoanalysis was almost impossible. Instead of being objective, self-reflective, tolerant, and accepting of each other’s views, they excluded and devalued each other. This prevented any constructive discussion of their theoretical differences. However, Freud’s idea of the individual unconscious and Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious do not contradict each other. TheyThey are like two sides of a coin, complementing each other and helping to understand the complexity of the human psyche.

Freud and Jung and their Psychological Types

With the publication of “Psychological Types,” and the book’s popularity, Jung became publicly recognized to a broader audience. Freud, disgruntled, dismissed “Psychological Types” as the work of a snob and mystic.

The conflicting views of Freud and Jung mirrored the personalities of both men. Freud being extraverted and Jung introverted, naturally destined them to opposition. This division extends until today to those who either enthusiastically embraced or categorically rejected Jung’s theories, shaping both Jungian psychology and Freudian theory.

The fundamental disparity between their personalities cannot be separated from their theoretical standpoints. Since the pioneers of C.G. Jung Sigmund Freud depth psychology also derived their insights from themselves, the subject and object of research largely overlapped. The result of research is always influenced by the subjective perception of the researcher, as the observer is by default intertwined with the observed event.

Another noteworthy distinction lies in their temporal perspectives. Freud tended to look backward, focusing on adaptive concerns and goals, while Jung inclined to look forward, emphasizing adaptive concerns and goals. This contrast becomes evident not only in their approaches to art but also in their approaches to mental illnesses. Jung came to nub of the matter when rehearsing his differences with Freud. In 1920 he wrote:

“Philosophical criticism has helped me to see every psychology – my own included – has the character of a subjective confession ... Even when I am dealing with empirical, I’m necessarily speaking about myself”

CW IV, para. 774

Freud’s and Jung’s Differences and their Backgrounds

Jung believed that his differences with Freud stemmed from his own introversion contrasting Freud’s extraversion. While this explanation holds some truth, it fails to give due consideration to other significant factors. Both men hailed from vastly different backgrounds. Freud, with his Jewish-urban socialization, was nurtured by a young and beautiful mother. He received an education rooted in progressive traditions, and by default he naturally gravitated towards science. In contrast, Jung, a Protestant, had an insecure bond with his depressed mother and was deeply influenced by theology and German romantic movement.

Following their different upbringing and life circumstances, it’s not surprising that Freud adopted a sceptical empiricism, believing in the leading role of sexuality. He studied the psyche “from outside,” like an object, in a typical scientific manner. On the contrary, Jung perceived the psyche “from within” as a creation on its own. From such perspective, he proposed a different concept of the psyche, seeing sexuality only as a part of his broader concept of libido.

“Here I could not agree with Freud. He considered the cause of the repression to be a sexual trauma. From my practice, however, I was familiar with numerous cases of neurosis in which the question of sexuality played a subordinate part, other factors standing in the foreground for example, the problem of social adaptation, of oppression by tragic circumstances of life, prestige considerations, and so on. Later I presented such cases to Freud; but he would not grant that factors other than sexuality could be the cause. That was highly unsatisfactory to me.”

C.G. Jung. “Memories, Dreams, Reflections”

Read More about Jungian Psychology

- Carl Gustav Jung. A Short Biography

- Psychology of Carl Gustav Jung

- The Collective Unconcious

- The Self

- The Individuation

- The Archetyps

- Archetyps. The Redicovered Theory

- The Ego and The Persona

- The Shadow

- The Animus and The Anima

- The Archytypal Neurosis

- Jungian Psychology and the Brain Structure

- Brain Evolution and Psychology

- Synchronicity

- Jungian Dream Analysis

- C.G. Jung and Otto Gross

- C.G. Jung Psychological Types

- C.G. Jung’s Word Association Test

- The Spiritual Aspect of the Psyche (Jungian View)

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Dr. Gregor Kowal studied human medicine at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg, Germany, where he also earned his doctoral degree (PhD). He completed his specialization in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy with the Medical Chamber of Koblenz, Germany. In the following years, he held positions as Head of Department and Medical Director in various psychiatric hospitals across Germany. Alongside his clinical responsibilities, he served as a consultant expert for the Federal Court in Frankfurt, providing psychiatric evaluations in legal cases. Since 2011, Dr. Kowal has been working as the Medical Director of CHMC, the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Dubai, UAE. His specialist training includes extensive expertise in biological psychiatry and psychodynamic psychotherapy.