Introduction. Braid’s encounter with “animal magnetism”

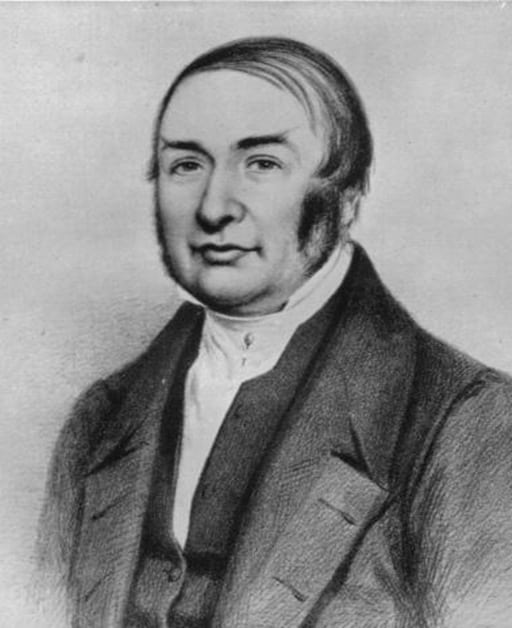

James Braid (1795-1860) was a Scottish surgeon and natural philosopher. Braid studied medicine in Edenborough and began his work as a surgeon. However, it was Braid’s work on hypnosis and hypnotism that immortalized his name. Today he is regarded as the “father of modern hypnotism”.

Braid laid the foundation for the scientific study of hypnosis and hypnotism, which was free from the metaphysical aura of animal magnetism.

On 13 November 1841, while living in Manchester, Braid attended the demonstration of “animal magnetism” by the Swiss mesmerist Charles Lafontaine. Braid initially rejected Lafontaine as a charlatan. He went to the event out of curiosity thinking he will witness bunch of rubbish. Braid participated in two more of Lafontaine’s demonstrations. After the presentation Lafontaine invited Braid and his fellow critics from the medical community to the platform. Braid examined the physical condition of Lafontaine’s “magnetized” (in today’s terms “hypnotized”) subjects. He found out that they were indeed in quite a different physical state. The demonstration and the discussion with Lafontaine convinced Braid that there was something worth investigating. Later he became interested in the phenomenon of hypnotism and dedicated his whole life to the research of the dynamics behind it.

Braid’s studies on “animal magnetism”

James Braid started his own experiments using as the first subjects his wife, a friend, and his servant. He soon came to the conclusion that he could reproduce many of the mesmerism phenomena in his subjects by having them fix their eyes on an object. He used the cork of a wine bottle with a shiny plated top to induce hypnosis.

James Braid repeatedly demonstrated that simply staring at a small, bright object could trigger a condition formerly known as “mesmeric somnambulism.” His groundbreaking work laid the foundation for what is now explored in practices such as German James Braid’s Hypnotism in Dubai, where modern techniques are inspired by his original methods.

In the process of inducing the “magnetic state” the followers of Anton Mesmer did hand passes over their subjects. Braid demonstrated that such passes were unnecessary. He proved that there was nothing related to an enigmatic “fluid” flowing from the subject to the mesmerized object. Even more, Braid discovered auto-hypnosis showing that anyone could hypnotize themselves by staring at an object.

Braid’s new terminology: Hypnosis and Hypnotism

As a methodical scientist Braid broke with the metaphysical doctrine of the “animal magnetism”. He replaced the disreputable expression “animal magnetism” with the word “hypnotism” and the process of “magnetizing” with the word “hypnosis”, terms we use until today. He laid the foundation for the scientific research on hypnotism. Braid called the phenomena after the Greek god of sleep and master of dreams, Hypnos.

In his 1843 published book, “Neurypnology or the rationale of nervous sleep considered in relation with animal magnetism” he listed and described the treatments and the cures he had achieved through hypnosis. He retrospectively compared his therapeutic healings by using hypnosis with the successes of mesmerism. Braid realized that the mesmerists have inadvertently stumbled upon something important. However, their “paranormal” explanations of the phenomena they evoked in their subjects marginalized their discoveries.

Braid used the hypnotic “implantation” of suggestions in his patients. He debunked the myth that people in a hypnotic state could break their moral codes.

Braid’s evolution of ideas

Braid was a modern time scientist. He was a medical man, not a showman, but a lucid writer, down-to-earth, cautious and indifferent to paranormal phenomena. He was dedicated to observations and experiments rather than preconceived notions. Today we would call his method “evidence based”. In fact, he was inclined to biological materialism and initially attributed hypnotic healing to changes in the body’s blood flow.

However, we shouldn’t forget that in each of us the “child of his time” lives within. So were James Braid and his predecessors Anton Mesmer, De Puységur and other mesmerists. Braid lived in the century where the progress of biological discoveries began to dominate the medical field. Mesmer and his followers were also embedded in the context of XVII century in which physics was the leading science with the discoveries of electricity, gravitation and magnetism. From the latter, Mesmer had borrowed the idea of “animal magnetism” trying to explain psychological phenomena in terms of physics.

James Braid was not afraid to correct and modify his ideas. He abandoned his earlier physiological hypothesis, which suggested that the fixation of a gaze affected blood flow from the eyes to the rest of the body, causing the hypnotic state. As his understanding evolved, James Braid acknowledged that focused attention and imagination played a critical role in inducing the hypnotic state and promoting healing.

In later years, James Braid hypnosis became more refined he could induce trance states simply by talking to his subjects. Remarkably, he even managed to hypnotize blind individuals through verbal suggestion alone. By the 1840s, James Braid realized that hypnotism could produce phenomena such as amnesia and anaesthesia in subjects. His psychologically oriented writings later anticipated much of the psychotherapeutic work that would emerge in the late nineteenth century, solidifying his legacy in the evolution of modern hypnosis.

Development of modern hypnotism

Braid found out that the hypnotized subject becomes occupied by a single idea to the exclusion of others. For such state he coined the term “monoidism”. He assumed that it might be possible to treat certain cases of hysteria by replacing the disturbing idea with another, more positive and life-affirming content. The modern day’s hypnotherapists call such method “reframing”.

Braid argued that the mind clearly influences the body. Since there is no doubt that the mind and body can interact and react to each other, it is only natural that some increase in mental powers is necessary. If a person can achieve that, he will have a correspondingly greater degree of control over his body and behaviour.

He distinguished between shallow and deep stages or layers of the hypnotic state. He called the first level, “sub-hypnotic”; the second he called “double consciousness” after having found his subjects dissociated (as we would now say) from their normal state. For example, he had his subjects learn some phrases in a foreign language. They were unable to remember the phrases while awake but could remember them later when hypnotized. Furthermore, Braid found out that hearing acuity in a deep trance was several times better than in th conscious state. A subject who in conscious state was able to hear ticking a watch from the distance of 3 feet, in trance the sound was audible from the distance of thirty-five feet. He found that in trance the autonomous body functions such as heartbeat can be controlled.

The integrative approach between hypnosis and biological medicine

Braid didn’t see hypnosis as a “panacea” for all medical conditions. He was well aware that similar diseases might arise from opposite medical conditions. Although he believed that hypnotic suggestion was a valuable treatment for nervous disorders, he did not consider it to be competitive with other treatments. He never separated hypnotism from general medicine. Braid wrote:

“I consider the hypnotic mode of treating certain disorders is a most important ascertained fact, and a real solid addition to practical therapeutics, for there is a variety of cases in which it is really most successful, and to which it is most particularly adapted; and those are the very cases in which ordinary medical means are least successful, or altogether unavailing. Still, I repudiate the notion of holding up hypnotism as a panacaea or universal remedy… I use hypnotism alone only in a certain class of cases, to which I consider it peculiarly adapted – and I use it in conjunction with medical treatment, in some other cases; but, in the great majority of cases, I do not use hypnotism at all, but depend entirely upon the efficacy of medical, moral, dietetic, and hygienic treatment, prescribing active medicines…”

The unrecognized pioneer of modern psychology

Braid was one of those researchers and a non-conformist, who didn’t care about the opinion of London’s medical establishment. Although some members of the medical community considered Braid’s work acceptable, there was too much opposition to widely appreciate the importance of his research. Braid’s research was rejected in England by the British medical community. Britain had condemned Braid’s views giving them the brush of occultism and eccentricity. No medical professional was ready to take the risk of investigating hypnotism out of fear of spoiling his career.

Braid was not only attacked by the British medical establishment. In April 1842 a controversial cleric Hugh Boyd M’Neil from St Jude’s Church, Liverpool, gave a sermon against mesmerism explicitly mentioning Braid. M’Neile’s argument was that mesmerism represents “satanic agency” and “witchcraft”. He associated Braid with Satan. He published his aggressive pamphlet in a newspaper. This was equal to character assassination threatening Braid’s professional and social position. James Braid’s reaction was that of a gentleman. He sent a private letter to M‘Neile with a detailed explanation on his scientific research. He even included with the letter a cordial invitation to his lecture he had delivered on the following Wednesday. M‘Neile did not acknowledge Braid’s letter, nor did he attend the lecture.

The “animal magnetism” or “mesmerism” went from France to Britain. Paradoxically it was a British doctor who prepared the scientific ground for the research on “hypnotism” and “hypnosis” and brought it back to the continent.

Braid paid a high price for his scientific dedication and moral strength. He was ostracized by the British medical community proving the role that a prophet is rarely welcomed or recognized in his home country.

Braid’s ideas about hypnosis crosses the English Channel

In 1860, ill and frustrated that his English colleagues had not understood the significance of his discovery, three days before his death, Braid sent his paper “On Hypnotism” to the French physician Étienne Eugène Azam. His paper intrigued many French psychologists with immense impact on French psychology. The newly arising interest in hypnotism and hypnosis in France shouldn’t be surprising as it was France that led the field for many years. We shouldn’t forget the pioneering work of Marquis De Puységur a few decades prior to Bernhaim’s research, which had popularized “animal magnetism” in France. It was also De Puységur who introduced standardizing records to prove the efficacy of “animal magnetism”. Although De Puységur’s research was ended by the French revolution, the memory of him and his discoveries were still present in the French scientific community.

James Braid died on 25 March 1860, in Manchester, not being able to witness the success of his lifelong research.

Conclusion

Braid is regarded today as the “Father of Modern Hypnotism”. His experimentation with self-hypnosis showed that the process of hypnotism did not rely on the gaze, charisma, or magnetism of the operator. Braid’s use of self-hypnosis was a crucial step towards understanding the true nature of hypnotism and dispelling popular misconceptions about the method. His exceptional achievement was the use of ‘self-‘ or ‘auto-hypnotism’, without an external interaction done entirely by himself, on himself. Braid believed that the key to hypnotism was not the operator’s techniques, but rather the state of the subject. However, his main achievements were helping to pull out the hypnosis from the dark corner of paranormal and occultism and facilitating the development of the psychodynamic psychology.

Braid’s paper gave a new impulse to French psychology. It was once again France which took over the lead in the field of psychology for the following decades. Braid’s discoveries on hypnotism restarted modern research in psychology. His work had a strong influence on a number of important French medical figures, especially Étienne Eugène Azam (Braid’s principal French “disciple”), and the hypnotherapist and co-founder of the Nancy School Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault, the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, neurologist Hippolyte Bernheim and the physician and psychologist Pierre Janet.

The French research on hypnosis influenced Sigmund Freud, who went to Paris and participated in Charcot’s lectures. Freud also used hypnosis at the beginning of his career, and it was his experience in the field of hypnosis which led later to the development of psychoanalysis.

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Senior Consultant in Psychiatry,

Psychotherapy And Family Medicine

(German Board)

Call +971 4 457 4240