Carl Gustav Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, along with Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler, was one of the founders of what is described today as depth psychology.

The work of Carl Gustav Jung exceeds, in its dimension, the field of psychology. His understanding of human psychology, or C.G. Jung psychology, stemmed from his individual experiences, dreams, and his introspective, self-analyzing abilities. He went beyond the demarcation line dividing psychology from philosophy and theology, investigating parapsychological and non-causal phenomena such as occultism, synchronicity, and intuition. His work laid the foundation for Jungian psychology, which continues to influence modern psychological practices.

After his departure from Freud, Jung developed his own psychotherapeutic technique, which he called “analytical psychology” to distinguish it from Freud’s psychoanalysis.

Jung’s innovative, multi-dimensional therapeutic concepts are no less than a “Copernican” revolution and a foundation on which a new science of psychology could be built. Potentially, they are of comparable importance to quantum theory in physics.

The following series of articles on the psychology of Carl Gustav Jung conveys to the interested reader just a glimpse of his monumental work and the richness of his ideas.

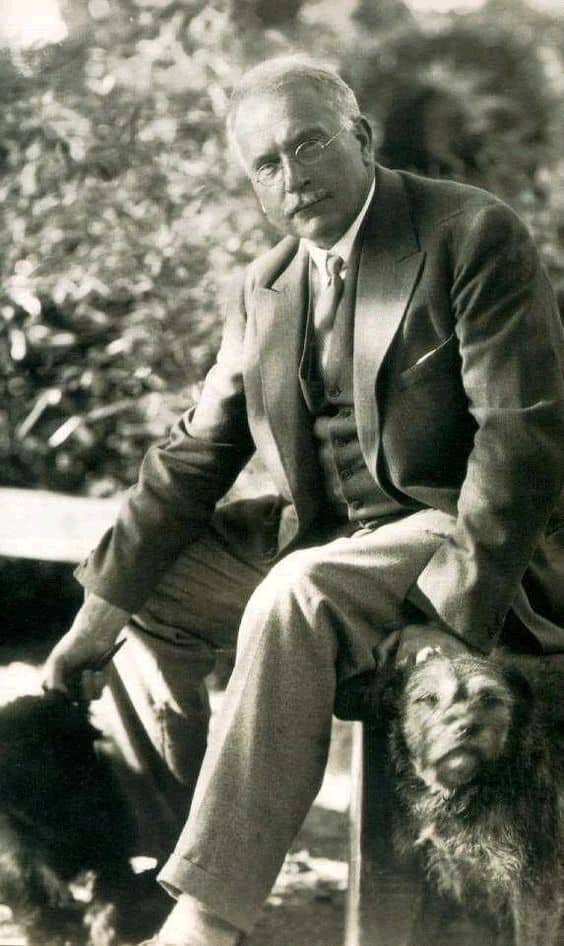

C.G. Jung’s Biographic Note

Carl Gustav Jung, born on July 26, 1875, in Switzerland’s Thurgau canton, was the son of a village pastor. Being a deeply introverted child and living isolated from his peers in a parish, he read books from his father’s library far beyond the “normal” interests of a boy of his age. He read works by philosophers such as Nietzsche and Kant and literature by Goethe, Schiller, and Shakespeare.

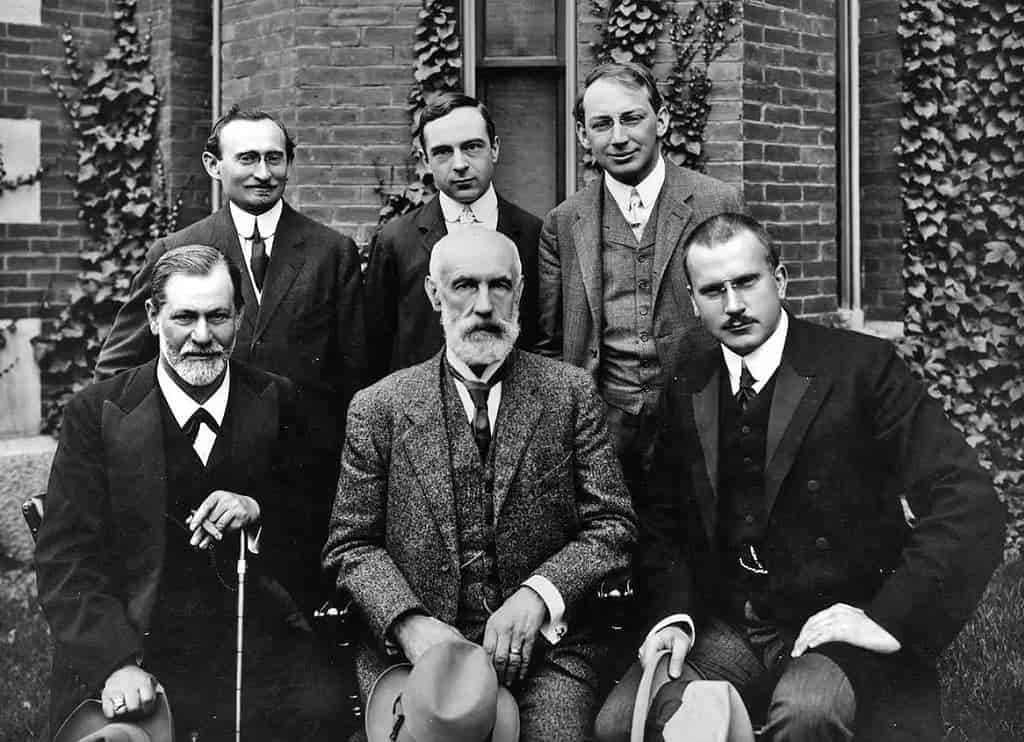

In 1895, Jung began studying medicine in Basel, and in 1900, he took a position at the Burghölzli psychiatric clinic in Zurich under the leading Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler. During this time, he first encountered Sigmund Freud’s writings. Their friendship started when Jung visited Freud in Vienna in 1907. His research on the Word Association Experiment provided evidence-based support for Freud’s psychoanalytical theory. However, their friendship soured in 1912 with the publication of Jung’s Transformations and Symbols of the Libido, in which Jung expressed different views on the origin of libido.

Jung became renowned as the founder of analytical psychology. Until his death on June 6, 1961, he continued to be highly prolific, publishing numerous works on the psychology of the unconscious as well as on religious and cultural themes. His life’s journey, marked by introspection and exploration, left an indelible mark on the field of psychology.

Background and Personality

Predestined to swim against the torrent, Jung’s intriguing personality demands acknowledgment in the context of his psychology. Jung was an excellently educated man and a productive writer. His interests went beyond his scholarly education, which was in medicine, psychiatry, and psychology. He had vast knowledge of mythology, religion, and philosophy, which he deepened throughout his long life. His native language was German, but he was also fluent in French, English, Latin, and ancient Greek.

Though a rational scientist, he embraced the irrational and esoteric, deeming a solely rational approach to psychology inadequate in a historical context. He had to adhere to the truth as he saw it.

Throughout his life, Jung remained deeply introverted, more interested in the inner world of dreams and images than the outer world of people and events. Since childhood, he possessed a genius for introspection, attentively observing experiences beneath the conscious threshold—experiences of which the great majority of us remain unaware. This gift was derived, at least in part, from the peculiar circumstances of his upbringing.

C.G. Jung’s Early Writings

Before meeting Freud, Jung authored a few publications that laid the foundation of his own psychology, which only partially overlapped with Freud’s analytical theory.

On Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena

Jung completed his medical studies in 1900 and began specializing in psychiatry, working as an assistant at the University Hospital Burghölzli in Zurich. In 1902, Jung wrote his dissertation titled On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena. The dissertation was inspired by spiritualistic sessions in which he participated during his studies. The medium in the séance was his maternal cousin, Helene Preiswerk, aged 16.

In the dissertation, Jung documented Helene’s trances, observing astonishing changes in her psychological state. While in a trance, Helene displayed a mature personality and spoke in high German, a language she was unable to use while conscious. Based on these observations, Jung concluded that the psyche has multiple dimensions, of which consciousness is only a small fraction. These phenomena catalyzed his concept of individuation, developed years later. According to this concept, individuation is a process of self-actualization achieved by uncovering and integrating the unconscious parts of the psyche. Jung’s study of Carl Jung archetypes and C.G. Jung analytical psychology contributed significantly to understanding the unconscious, while Jung dream analysis became a key tool in exploring and integrating these unconscious elements into the conscious mind.n the dissertation, Jung documented Helene’s trances, observing astonishing changes in her psychological state. While in a trance, Helene displayed a mature personality and spoke in high German, which she was unable to use while conscious. Based on these observations, Jung concluded that the psyche has multiple dimensions, of which consciousness is only a small fraction. These phenomena catalyzed his concept of individuation, developed years later. According to this concept, individuation is a process of self-actualization achieved by uncovering and integrating the unconscious parts of the psyche.

Psychology of Dementia Praecox

Working at the Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital under Eugen Bleuler, Jung observed patients with schizophrenia and analyzed psychotic phenomena from an analytical perspective. In 1907, he published his observations in his second book, The Psychology of Dementia Praecox, which enhanced his reputation as a research psychiatrist.

Jung’s burning question was: what actually takes place inside the mentally ill? Unlike most psychiatrists before or since, he gave serious attention to what his schizophrenic patients said and did. He demonstrated that their delusions and hallucinations were not simply “mad” but full of psychological meaning.

For instance, he observed an old schizophrenic patient who had spent fifty years in the Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital. The patient made stitching movements as if sewing shoes. Later, Jung discovered that, before her illness, she had been jilted by a cobbler lover. Jung connected the dots and assumed correctly that the emotional shock triggered her illness, and the stitching movements symbolized her tragic romance.

As a scientist, Jung believed that psychotic phenomena were associated with biochemical neurotoxins circulating in the brain. However, he also understood schizophrenia in psychoanalytic terms as “an introversion of libido.” He considered the libido to be withdrawn from the outer world of reality and invested in the inner world of myth-creation, fantasy, and dreams. The schizophrenic, he maintained, was a dreamer in a waking world.

“I had not met with much sympathy for the ideas expressed in “The Psychology of Dementia Praecox.” In fact, my colleagues laughed at me. But through this book I came to know Freud. He invited me to visit him, and our first meeting took place in Vienna in March 1907. We met at one o’clock in the afternoon and talked virtually without a pause for thirteen hours. Freud was the first man of real importance I had encountered; in my experience up to that time, no one else could compare with him. There was nothing the least trivial in his attitude. I found him extremely intelligent, shrewd, and altogether remarkable.”

C.G. Jung. “Memories, Dreams, Reflections”

Word Association Test

In 1903, Jung, together with his assistant Franz Riklin, started experiments with the word association test. The word association test was first used as a research instrument in 1879 by Francis Galton and later by Emil Kraepelin and Wilhelm Wundt. A standard association test involved timing quick responses to trigger words. Galton, Kraepelin, and Wundt used the test to measure a patient’s cognitive fitness.

All of the previous reserchers were primarily interested in the content and speed of the responses, without being able to identify the reasons for the delays. The concentrated on the positive results and not on the abberations.

Jung’s Unique Approach to Word Association Test

The test was initially developed by Francis Galton to evaluate the neurocognitive abilities of patients, focusing on correct and quick responses. Jung, however, shifted the focus to the mistakes made during the test, such as prolonged responses or a lack of responses altogether. He discovered that words causing disturbances “touched” the patient’s emotional complexes. Following this logic, Jung correctly assumed that these emotionally charged complexes operated autonomously in the unconscious, blocking the patient’s self-expression, increasing reaction times, or “twisting” their answers.

Jung recognized the significance of this discovery and linked it to Freud’s analytical theory, particularly the mechanism of repression. He sent the test results to Sigmund Freud, who acknowledged them as experimental proof of his theory. In 1907, Jung met Freud in Vienna, marking the beginning of a period of close collaboration and friendship.

The research on the Word Association Test was also the reason for Jung’s invitation to the famous Clark University lecture in 1909.

Developement of C.G. Jung’s Psychology

Befor meeting Freud Jung developed the foundation of his own psychology which only partially overlaped with Freud’s analytical theory. In his autobiography “Memories, Dreams , Reflections” Jung concluded:

“In 1903 I once more took up (Freud’s) “The Interpretation of Dreams” and discovered how it all linked up with my own ideas. What chiefly interested me was the application to dreams of the concept of the repression mechanism… This was important to me because I had frequently encountered repressions in my experiments with word association; in response to certain stimulus words the patient either had no associative answer or was unduly slow in his reaction time. As was later discovered, such a disturbance occurred each time the stimulus word had touched upon a psychic lesion or conflict…

In the course of his collaboration with Freud, the differences gradually became apparent. Although Jung agreed with the concept of repression, and adopted the term “libido”, he interpreted them differently than Freud—not exclusively driven by sexuality. In doing so, he did not deny the significance of sexuality, but viewed it as one expression of the overall life force.

My reading of Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams” showed me that the repression mechanism was at work here, and that the facts I had observed were consonant with his theory. Thus, I was able to corroborate Freud’s line of argument. The situation was different when it came to the content of the repression. Here I could not agree with Freud. He considered the cause of the repression to be a sexual trauma. From my practice, however, I was familiar with numerous cases of neurosis in which the question of sexuality played a subordinate part, other factors standing in the foreground for example, the problem of social adaptation, of oppression by tragic circumstances of life, prestige considerations, and so on. Later I presented such cases to Freud; but he would not grant that factors other than sexuality could be the cause. That was highly unsatisfactory to me.”

C.G. Jung. “Memories, Dreams, Reflections”

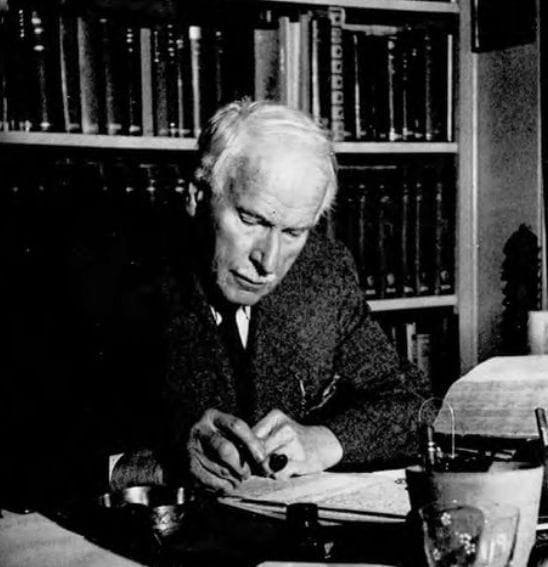

Reading Jung’s Writings

In contrast to Freud, who gave his work a systematic structure, Jung left his writings in a less organized form. The complexity of his ideas, as well as his writing style, is the major entry barrier for those interested in Jungian psychology. His nonlinear writing style reflects his thinking, as he approaches the subject repeatedly, each time from a different angle. Jung never settles for a single formulation but continually redevelops concepts related to a particular context. This approach infuses his work with richness but demands the reader’s utmost mental flexibility.

Reading Jung’s work requires determination. Apart from the long and sometimes reciprocal sentences, the reader must follow Jung from the depths of psychiatric practice to the ivory tower of philosophy and religion. The concept of a collective unconscious and the notion of libido as a driving force for self-realization, expressed through the “circular” descriptions typical of Jung’s writings, make it difficult for many readers to grasp the fundamentals. Another difficulty in understanding his ideas is the vast material he provids about world religions and mythologies.

Understanding Jung

Jung was well aware of the weaknesses in his communication: “No one reads my books, and I have such difficulty making people understand what I mean.”

However, in Jung’s collected works, the reader will find brilliantly formulated and straightforward ideas. The author of this article refers the interested reader to Jung’s early books: The Psychology of Dementia Praecox, written in 1907, which remains the most sophisticated psychoanalytical interpretation of psychotic phenomena. Additionally, the transcripts of Jung’s lectures provide a good understanding of his psychology, particularly the Tavistock Lectures from 1936 held at Tavistock, UK: Analytical Psychology: Its Theory and Practice (Tavistock Lectures).

Jungian versus Freudian Psychology

Understanding depth psychology isn’t possible without immersing oneself in Jung’s conflict with Freud.

An undisputed achievement of Freud was the development of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic theory—the first effective method for treating mental health disorders and a foundational model of the dynamics of the human psyche. Freud also originated much of the language still used today in analytical psychology.

For a time, Jung was even considered by Freud to be the “crown prince” destined to carry on his work. Even after their separation, Jung continued to acknowledge Freud’s contributions to the exploration of the unconscious. In contrast, in “On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement” (1914), Freud found it difficult to recognize any original achievement on Jung’s part. According to Freud, Jung had brought forth little that was new, merely renamed what was already known and weakened essential parts of psychoanalytic theory.

The Differences

The main difference between Freudian and Jungian psychology is their distinct approach to the psyche. While Freud applied the principle of causality from natural science to the study of the psyche, Jung viewed psychological processes as acausal and considered the psyche an entity independent of matter, and not bound by space or time.

From today’s perspective, Freud’s libido concept and his dream interpretation method proved to be wrong while Jung’s stood the test of time. However, it is Freud’s analytical theory which entered the “pantheon of science”, while Jung and his psychology are considered as non-scientific or even esoteric.

The Jungian psychologist James Hillman compared Freudian psychology to the catholic church consolidated by a dogma. He saw the “dogma-free” Jungian psychology on the opposite pole, comparing it to the protestant church splitting from the common trunk into dozens of branches. This explains the fragmentation of Jungian societies around the world.

Collective Unconscious in C.G. Jung’s Psychology

Carl Gustav Jung disagreed with the idea that humans are born as a “tabula rasa,” a blank slate proposed by ancient philosophers like Aristotle and later, in the 17th century, by René Descartes and John Locke. Instead, Jung introduced the concept of the “collective unconscious.” He described the collective unconscious as an inherited layer of the human psyche, equipped with universal experiences common to all humans. This layer exists beneath the “personal unconscious” of repressed wishes and traumatic memories discovered by Freud.

Jung developed the concept of the collective unconscious based on his own experiences. Even as a child, possessing a remarkable gift for introspection, he realized that there were things in his dreams that came from somewhere beyond himself. During his research as a psychiatrist, he found symbols and images in the delusions and hallucinations of schizophrenic patients that also appeared in myths and fairy tales.

The Archetypes

Through numerous intercultural studies, travels, encounters with indigenous peoples, and the study of myths, and literature, as well as through observing his psychiatric patients, Jung identified common images and ideas that appear collectively throughout human history. He referred to these entities as “archetypes.”

Jung described archetypes as universal, innate patterns of behavior that represent inherited knowledge passed down from our ancestors. They function as behavioral templates, or modi operandi, that are activated in specific life circumstances. Jung compared archetypes to dry riverbeds that fill with water after rain, suggesting that archetypes similarly become filled with content when activated in particular life situations.

The Archetypes of Anima and Animus

Just as gender is experienced as an affirmation of the archetypal principle appropriate to one’s sex, so relations with the other sex rest on archetypal foundation. Jung called this contra sexual archetype the animus in women and the anima in men. As feminine aspect of man and the masculine aspect of woman, they function as a pair of opposites in the unconscious, profoundly influencing the relations of all men and women.

The Persona

The Persona is a conformity archetype. It is our public face, or the “mask” we wear in different social situations. It is a product of adopting societal expectations, roles, commands, and prohibitions.

The Shadow Archetyp

The shadow is the opposite to the persona. It encloses our “hidden site”, repressed aggressive impulses, desires, and instincts. Common manifestations of the shadow include envy, greed, prejudice, hate, and aggression. However, the shadow contains not only the darker, unacknowledged aspects of our personality but also its untapped potentials. Its integration is crucial for personal growth and ethical living.

Archetypal Neurosis

Every living organism has an anatomical structure and a behavioral repertoire that is uniquely adapted to the environment in which it evolved. This is the “environment of evolutionary adaptation” in which individuals will live out their life cycle. Any change in the environment has consequences for the organism.

Human versatility, has led to dramatic transformations of the environments in which we live. In fact, the speed at which environments have changed in recent centuries has far outstripped the pace at which natural selection can progress in the traditional Darwinian manner. Today we live in overcrowded, polluted cities, being constantly exposed to stress. Such environment causes the frustration of the archetypal needs leading inevitably to mental health disorders appearing in the shape of “archetypal neuroses.”

The Individuation Process

According to Jung, individuation is the ultimate goal of human life, enabling the exploration and realization of the full potential of the unconscious. He believed that the purpose of analytical psychology is to support this process by integrating the Ego (the conscious mind) with the Self (the totality of the psyche).

Individuation should not be confused with ego-centeredness or individualism. To fully grasp the concept, it is essential to understand Jung’s organization of the psyche. In Jungian psychology, the Self represents the totality of personality, encompassing both the conscious and unconscious. The Self is superior to the Ego, as it connects to the collective unconscious and holds the shared knowledge of our species. Exploring the Self helps the Ego in achieving its most complete expression of individuality freeing it from superficial or false identities.

Individuation does not arise through adaptation to external expectations, but through engagement with one’s own often contradictory inner reality. Jung had already criticized a spirit of the times that strives to appear perfect on the outside, yet loses contact with the inner self.

The Phases of Individuation

The individuation process is not a one-time step, but a lifelong dialogue between the conscious and the unconscious. Jung emphasizes that conflicts and crises are essential components of this process—they challenge us, make us feel alive, and help us unfold our uniqueness. Individuation as a multi-stage process involvs various inner encounters and integrations:

Shadow Confrontation

The first step is the confrontation with what is known as the shadow—those aspects of the personality that we have repressed or split off. These are usually unpleasant traits, unwanted emotions, fears, or aggressions. However, unconscious resources can also lie within the shadow. Encountering these aspects is often painful—but necessary for any profound personal development.

Integration of Anima/Animus

The next phase is the integration of the psyche’s inner opposite-sex component. For men, this inner polarity appears as the anima (the feminine soul element); for women, as the animus (the masculine soul element). Consciously encountering this polarity broadens the personality and fosters inner balance.

Unification with the Self

At the end stands the realization of the Self as the overarching instance of the personality, which unites all aspects—both conscious and unconscious. Individuation does not mean becoming “perfect,” but becoming “whole.” The final phase describes the deeper integration of all parts of once personality. Through this, an inner harmony arises that makes life meaningful, vibrant, and authentic.

Synchronicity

Jung introduced the concept of synchronicity, he called also meaningful coincidence, into his psychology. He observed events occurring simultaneously that were not causally connected but were linked by their content. An example of such an acausal phenomenon might be thinking of an old friend we haven’t seen in years, only to receive a phone call from that very person at the same moment. Synchronistic phenomena are familiar to all of us, but they are often dismissed as “mere coincidence.”

If synchronistic events are acausal, they transcend the boundaries of linear cause-and-effect relationships and point to a non-material psychic existence beyond the time and space.

Jung’s Typology

In 1921 in his bestseller book, “Psychological Types” Jung proposed his concept of typology. Jung assumed that people share a common psychological foundation for perceiving and responding to the world, both externally and internally.

Jung’s theory of psychological types has its roots in his biography, as he grappled with typological duality from a young age. He labelled the concrete, outwardly-oriented, socially compatible side “Personality No. 1,” distinguishing it from “Personality No. 2,” the inwardly, unconscious and wise aspect of his personality.

In “Psychological Types” Jung proposed the concept of four functions of the psyche: two non-rational functions: Sensation and Intuition, and two rational functions: Thinking and Feeling. Those functions are interlinked with two main attitudes: Extraversion and Introversion. “Extraversion” implies outward-directed psychic energy, whereas “introversion” denotes energy drawn inward. Combining two attitudes and the four function Jung distinguished eight personality types.

Jungian Dream Analysis

Sigmund Freud’s book “The Interpretation of Dreams” dominated the field of dream analysis. In Freud’s view the book was his biggest achievement and contribution to science. However, it was Carl Gustav Jung who found that dreams are not just “guardians of sleep” of vehicles for “wish fulfilments.”

In Jung’s view dreams are structured narratives fundamental for our survival and adaptation. They are “living fossils” preserving the knowledge of our species throughout time. They bridge the gap between our Palaeolithic ancestry and modern society interconnecting human consciousness with evolutionary heritage.

Jungian versus Freudian Psychology

Understanding depth psychology isn’t possible without immersing oneself in Jung’s conflict with Freud.

An undisputed achievement of Freud was the development of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic theory—the first effective method for treating mental health disorders and a foundational model of the dynamics of the human psyche. Freud also originated much of the language still used today in analytical psychology.

For a time, Jung was even considered by Freud to be the “crown prince” destined to carry on his work. Even after their separation, Jung continued to acknowledge Freud’s contributions to the exploration of the unconscious. In contrast, in “On the History of the Psychoanalytic Movement” (1914), Freud found it difficult to recognize any original achievement on Jung’s part. According to Freud, Jung had brought forth little that was new, merely renamed what was already known and weakened essential parts of psychoanalytic theory.

The Differences

The main difference between Freudian and Jungian psychology is their distinct approach to the psyche. While Freud applied the principle of causality from natural science to the study of the psyche, Jung viewed psychological processes as acausal and considered the psyche an entity independent of matter, and not bound by space or time.

From today’s perspective, Freud’s libido concept and his dream interpretation method proved to be wrong while Jung’s stood the test of time. However, it is Freud’s analytical theory which entered the “pantheon of science”, while Jung and his psychology are considered as non-scientific or even esoteric.

The Jungian psychologist James Hillman compared Freudian psychology to the catholic church consolidated by a dogma. He saw the “dogma-free” Jungian psychology on the opposite pole, comparing it to the protestant church splitting from the common trunk into dozens of branches. This explains the fragmentation of Jungian societies around the world.

Jung’s Contribution to Psychology

Freud saw the unconscious as a container of forgotten or displaced individual memories. He followed the concept of “tabula rasa,” seeing the newborn child as an empty slate starting to accumulate experiences and memories only after birth. In contrast to Freud, Jung discovered within the unconscious a deeper layer embracing the condensed knowledge of humanity developed throughout evolution. He termed this condensed inherited knowledge the “collective unconscious.”

He introduced to psychology terms such as “introversion”/ “extroversion,” “conflict,” the concepts of the collective unconscious, archetypes, personality typology, and synchronicity. However, his most unique contribution was the concept of the collective unconscious and archetypes.

Through studies of myths, art, and literature, as well as observations of his patients, Jung repeatedly encountered common images and ideas that exist collectively throughout human history. He called these entities “archetypes,” which are inherited patterns of behavior that help individuals adapt to their changing life circumstances.

He investigated archetypes seeing in them innate neuropsychic centres’ possessing the capacity to initiate, control, and mediate the human behavioural. Thus, on appropriate occasions, archetypes give rise to similar thoughts, images, myths, feelings, and ideas in people, irrespective of their class, creed, race, geographical location, or historical epoch.

An individual’s entire archetypal endowment makes up the collective unconscious, whose authority and power are vested in a central nucleus responsible for integrating the whole personality, which Jung termed the Self.

Jungian Psychology Today

Today, Jung and his psychology remain even more controversial and confusing than in the first part of the twentieth century, which was dominated by psychoanalysis and its various branches, called depth or psychodynamic psychology.

There are several obstacles to Jungian psychology entering the mainstream of science, particularly in psychiatry and psychology. In general, psychiatrists are seldom trained in depth psychology, and those familiar with Jungian psychology are extremely rare. Psychologists, on the other hand, especially those rooted in behaviorism and neurophysiology, rejected Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious and his approach to the psyche.

The current scientific effort in psychiatry and psychology is to explain the psyche as a pure epiphenomenon of brain function. In contrast, Jung rejected the concept of “biologizing” the psyche. He treated the psyche as a creation of its own, independent of matter.

Another reason for the rejection of Jungian psychology by established science is the introduction of non-causal phenomena like intuition or synchronicity, which collide with the causality on which Western thought is built. As a result, Jungian psychology has an esoteric aura and is considered non-scientific.

Jung’s Multidimensional View on the Psyche

Jung’s psychology became also a cosmology, for he saw the journey of personal development towards fuller consciousness as occurring in the context of eternity.

The psyche, existing sui generis as objective part of nature, is subject to the same laws that govern the universe and is itself the supreme fulfilment of those laws. Through the miracle of consciousness, the human psyche provides the mirror in which nature sees herself reflected.

First 100 years later the quantum physisists confirm Jung’s view.

Quantum Information Explained | Federico Faggin

Jung on the Psyche

“The psyche deserves to be taken as a phenomenon in itself, for there are no grounds for regarding it as a mere epiphenomenon, even though it is associated with the function of the brain; just as little as one can conceive of life as an epiphenomenon of the chemistry of carbon.” Contributions to Analytical Psychology, p. 6. London: Kegan Paul, 1928.

Jung says further:

“We can very well determine with sufficient certainty that an individual consciousness with reference to ourselves has come to an end in death. Whether, however, the continuity of the psychic processes is thereby broken remains doubtful, for we can today assert with much less assurance than fifty years ago that the psyche is chained to the brain. On the contrary, it appears that the psyche is not bound to space and time. The unconscious manifests itself in such a way that it seems to stand outside of them; it is spaceless and timeless. ” Wirklichkeit der Seele, p. 212. Zürich: Rascher, 1934

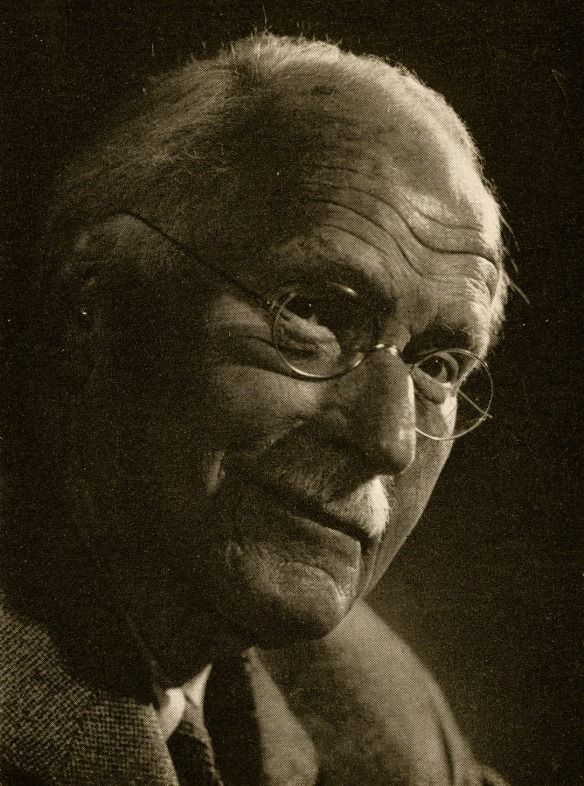

Jung’s Reflections on His Life

Looking back on his life, Jung reflected:

“In my case, it must have been a passionate urge to understand that brought about my birth. For that is the strongest element in my nature” (MDR 297).

In old age, Jung had many premonitions of approaching death, and what pressed him was the lack of fuss the unconscious makes about it. Death for Jung seemed to be a goal in itself, something to be welcomed.

Jung’s needs to “understand and to know” kept him creatively alive well into his eighty-sixth year, when he suffered two strokes and died peacefully on 6 June 1961 at Küsnacht.

Read More about C.G. Jung’s Psychology

- The Collective Unconcious

- The Self

- The Individuation

- The Archetyps

- Archetyps. The Redicovered Theory

- The Ego and The Persona

- The Shadow

- The Animus and The Anima

- The Archytypal Neurosis

- Jungian Psychology and the Brain Structure

- Brain Evolution and Psychology

- Synchronicity

- Jungian Dream Analysis

- Freudian and Jungian Models of the Psyche

- Sigmund Freud, C.G. Jung. Friendship, Collaboration, Differences

- C.G. Jung and Otto Gross

- C.G. Jung Psychological Types

- C.G. Jung’s Word Association Test

- The Spiritual Aspect of the Psyche (Jungian View)

Videos about Jung

Face To Face with Carl Gustav Jung (1959)

Interview with C.G. Carl Jung 1957

“Matter of Heart” – Documentary on Carl Gustav Jung

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Dr. Gregor Kowal studied human medicine at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg, Germany, where he also earned his doctoral degree (PhD). He completed his specialization in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy with the Medical Chamber of Koblenz, Germany. In the following years, he held positions as Head of Department and Medical Director in various psychiatric hospitals across Germany. Alongside his clinical responsibilities, he served as a consultant expert for the Federal Court in Frankfurt, providing psychiatric evaluations in legal cases. Since 2011, Dr. Kowal has been working as the Medical Director of CHMC, the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Dubai, UAE. His specialist training includes extensive expertise in biological psychiatry and psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Sources

Jung, C.G.; Aniela Jaffé (1965). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Random House. p. v.

Collected Works of C.G. Jung”. Princeton University Press. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

Jung, Carl Gustav. Psychology and the Occult. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978

Bair, Deirdre (2003). Jung: A Biography. New York: Back Bay Books.

Gay, Peter (1995). Freud: A Life for Our Time. London: Papermac.

The BBC interviewed Jung for Face to Face with John Freeman at Jung’s home in Zurich in 1959

Carl Jung (1959). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, Volume 9, Part 1. Princeton University Press

Stevens, Anthony (1994): Jung: A very short introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford & N.Y. ISBN 978-0-19-285458-2

Jung, Carl Gustav & Riklin, Franz Beda: Diagnostische Assoziationsstudien. I. Beitrag. Experimentelle Untersuchungen über Assoziationen Gesunder (pp. 55–83). 1904, Journ. Psych. Neurol., 3/1-2. – Hrsg. v. August Forel & Oskar Vogt. Red. v. Karl Brodmann. – Leipzig, Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1904, gr.-8°, Jung, Carl (1963).

Freud, Sigmund. “The Interpretation of Dreams”. Classics in the History of Psychology. Retrieved 19 August 2023.Hall, James (1983).

Jungian Dream Interpretation: A Handbook of Theory and Practice. Inner City Books. ISBN 0-919123-12-0.

Storr, Anthony (1983). The Essential Jung. New York. ISBN 0-691-02455-3.

Jacobi, J. (1973), The Psychology of C. G. Jung. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Jung, C.G. (1948). General aspects of dream psychology. In: Dreams. trans., R. Hull. Princeton, NJ:

“Michel Jouvet: Sleep research pioneer (1925 – 2017)”. aasm.org. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. October 4, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

“Kleitman, father of sleep research.” University of Chicago Chronicle V. 19(1), Sept. 23, 1999. University of Chicago. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

Kleitman, N., Sleep and Wakefulness, 1963, Reprint 1987: ISBN 9780226440736

The tribal imagination: Civilization and the savage mind. Harvard University Press. 2011. pp. 417. ISBN 978-0-674-05901-6

Stevens, Anthony, Archetype Revisited: An Updated Natural History of the Self. Brunner-Routledge, London; Inner City Books, Toronto.