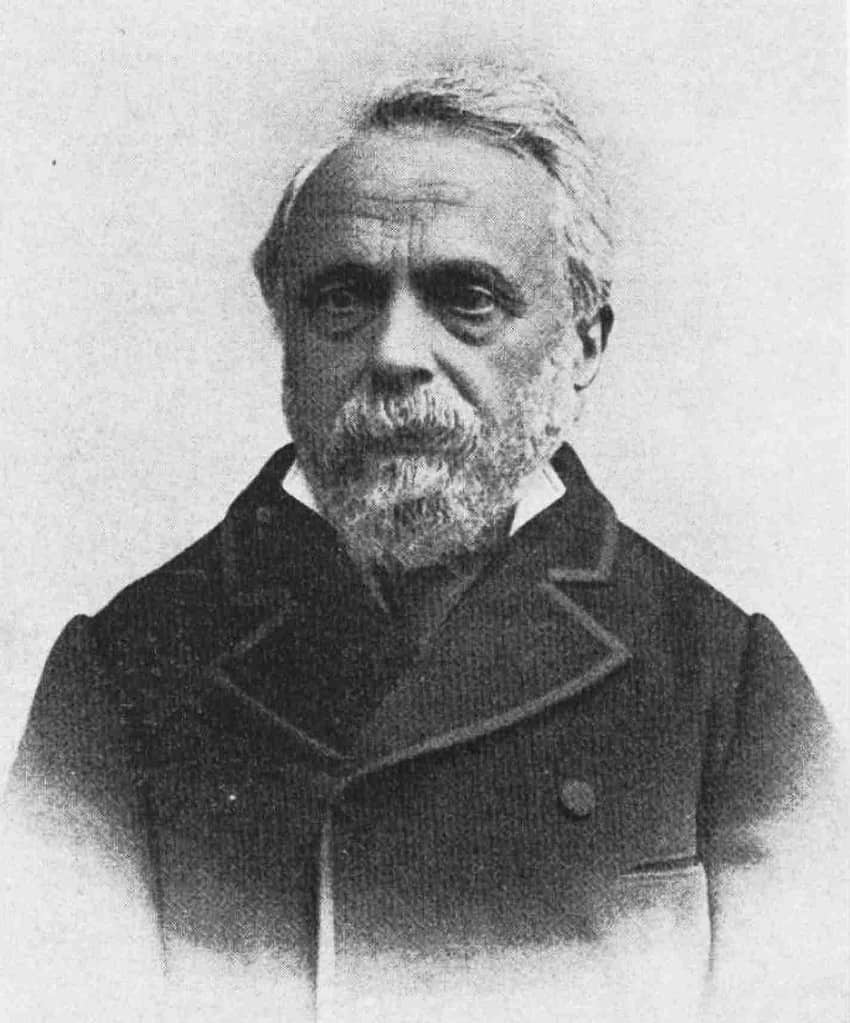

Liebeault. The founder of the Nancy School

Between 1860 and 1880, the reputation of magnetism and hypnotism hit rock bottom. Physicians who employed these techniques risked damaging their scientific careers and losing their medical practices indefinitely.

However, amidst the prevailing fear, Auguste Ambroise Liebeault (1823-1904) emerged as one of the few brave souls who openly embraced hypnotism. This bold move would pave the way for the renowned Nancy School.

Born into a humble peasant family, Liebeault was the twelfth child, residing in the Lorraine province. Through sheer determination, he rose to become a rural physician in Pont-Saint-Vincent, a village situated not far from Nancy. Within a decade, his exceptional skills garnered him great success, amassing a modest fortune.

The revival of hypnosis

During his medical studies, Liebeault stumbled upon an antiquated book on magnetism, showing him the technique through which he successfully hypnotized some of his patients. In the meantime, the old-fashioned term introduced by Anton Mesmer “magnetism” has been replaced by Braid who introduced the contemporary description “Hypnotism”. What motivated Liebeault to employ this method after it had fallen out of favour for so many years remains unknown. Aware of his clients’ reservation, he offered them an alternative: free hypnotic treatments or conventional medical care for his customary fee. Astonishingly, the number of patients opting for magnetism skyrocketed, leading to Liebeault amassing an extensive clientele within just four years. Unfortunately, this newfound popularity failed to translate into financial gains.

Liebeault’s writing career

In light of this predicament, Liebeault made a pivotal decision. He took a two-year hiatus from his professional life and retreated to his recently purchased house in Nancy. There, he dedicated all his time to writing a comprehensive book, “Induced Sleep and States Analogous to It,” outlining his method.

According to him, hypnotic sleep was synonymous with natural sleep the sole disparity being that the former was induced through suggestion, achieved by concentrating on the idea of sleep. This understanding formed the philosophical and clinical backbone of what would later be recognized as part of the German Nancy School Influence in Dubai, where suggestion-based therapies have found renewed relevance.

Liebeault’s view on hypnotic sleep continues to inspire modern practices such as sleep therapy Dubai, where natural, non-pharmacological approaches to insomnia and related disorders are growing in popularity.

Moreover, his emphasis on the therapeutic power of suggestion laid groundwork for effective depression therapy Dubai, where mental wellness is approached holistically, drawing from both modern psychology and historical insights into hypnotic states.

Unfortunately, Liebeault proved to be a more proficient hypnotizer than writer. Over the span of a decade, only few copies have been sold. Undeterred, he resumed his medical practice, offering consultations from 7:00 a.m. until noon and accepting only voluntary fees from his patients.

Liebeault and Bernhmeim. Introducing hypnotism into medical practice

The Nancy School, spearheaded by Auguste Ambroise Liebeault, challenged the prevailing skepticism surrounding hypnotism. Through his pioneering work and unwavering commitment to patient care, he redefined the boundaries of medical practice, leaving an indelible mark on the field.

During Liebeault’s belated rise to fame, a person visiting his clinic at that time, described him as a lively, chatty man with a wrinkled face, dark complexion, and peasant-like appearance. In an old shed with whitewashed walls and flat stone flooring, Liebeault attended to twenty-five to forty patients each morning. He conducted public treatments, unfazed by the surrounding noise. By ordering patients to gaze into his eyes and suggesting increasing drowsiness, Liebeault induced a mild state of hypnosis. Once entranced, he assured them that their symptoms had dissipated.

Most of his patients hailed from the city’s impoverished population or neighbouring peasants. Liebeault employed the same method to treat different ailments. He treated not only psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, phobias but also wide range of physical illnesses, from arthritis and ulcers to icterus and pulmonary tuberculosis.

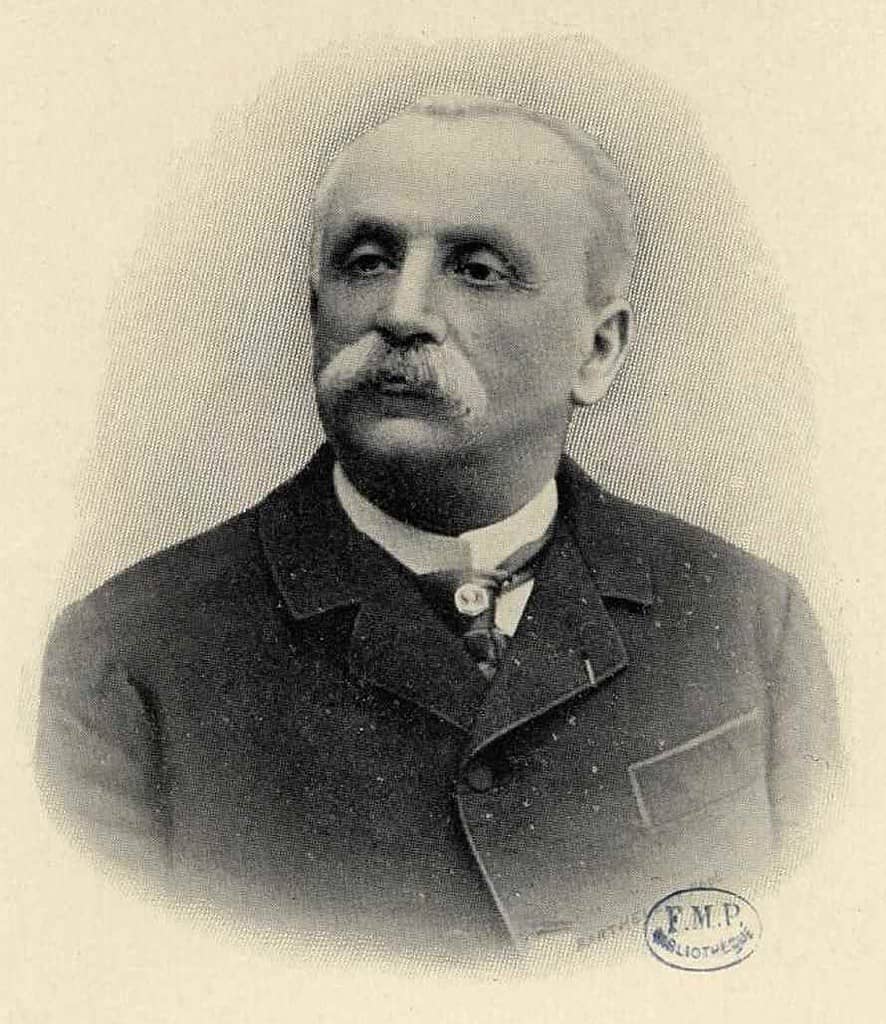

Hippolyte Bernheim

For over two decades, Liebeault’s medical colleagues dismissed him as a charlatan for his use of hypnosis and a fool for refusing payment. However, rumours of his therapeutic miracles reached Hippolyte Bernheim, prompting him to visit Liebeault in 1882. Astonishingly, Bernheim, a renowned professor, embraced Liebeault’s methods and became his ardent admirer, pupil, and close friend.

The Breakthrough

In a remarkable turn of events, Bernheim, previously esteemed for his research on typhoid fever, heart conditions, and pulmonary diseases, publicly endorsed Liebeault’s approach. He introduced it to the medical hospital at his university, rescuing Liebeault’s previously overlooked book from obscurity. As a result, Liebeault gained recognition as a prominent medical figure. While Liebeault could be considered the spiritual father of the Nancy School, the actual leader was Hippolyte Bernheim (1840-1919).

The Nancy University

Bernheim, originally from Alsace and a staunch French patriot, left his positions at the hospital and university in Strasbourg after its annexation by the Germans in 1871. He relocated to Nancy, a vibrant city energized by an influx of Alsatian refugees and the establishment of a new university in 1872.

In 1879, Bernheim’s established reputation earned him the title of titular professor of internal medicine at the new university. Three years later, in 1882, he experimented with and embraced Liebeault’s hypnotic method, albeit selectively, utilizing it only when he believed it had a good chance of success. Van Renterghem characterized Bernheim as a short, blue-eyed man who spoke softly but possessed an authoritative manner when dealing with his hospital ward and hypnotizing his patients.

According to Bernheim, hypnosis was more easily induced in individuals accustomed to passive obedience, such as old soldiers or factory workers, among whom he achieved the best therapeutic outcomes. Conversely, he encountered less success with individuals from higher social classes.

Bernheim’s struggle against Charcot and the rise of the Nancy School

Following Charcot’s renowned paper on hypnotism at the Académie des Sciences, Bernheim wasted no time in exposing Liebeault’s work to the medical community. This marked the beginning of a bitter rivalry between the two men. In 1886, Bernheim achieved great success with the publication of his textbook, which catapulted him to the forefront as the leader of the Nancy School.

In direct opposition to Charcot, Bernheim emphatically declared that hypnosis was not a pathological condition exclusive to hysterics. Instead, he argued that it was an outcome of “suggestion.” Bernheim defined suggestibility as the innate ability of every individual to translate an idea into action, albeit to varying degrees. According to his view, hypnosis represented a state of induced suggestibility through suggestion.

Bernheim harnessed hypnotism as a therapeutic tool for a wide range of organic nervous system disorders, including rheumatism, gastrointestinal ailments, and menstrual irregularities. He vehemently dismissed Charcot’s theory of hysteria and boldly proclaimed that the hysterical conditions observed at the Salpêtrière Hospital were nothing more than manufactured phenomena.

Coining the term “psychotherapy”

As time progressed, Bernheim gradually relied less on hypnotism, asserting that the effects achieved through this method were equally attainable through waking-state suggestion. The Nancy School coined the term “psychotherapy” to describe this approach. However, it’s important to note that Bernheim, an internist rather than a psychiatrist, lacked a cohesive following or organized school.

In its narrower interpretation, the Nancy School consisted of four key figures: Liebeault, Bernheim, the forensic medical expert Beaunis, and the lawyer Liegeois. The latter two individuals were particularly engrossed in exploring the ramifications of suggestion in relation to crime and criminal responsibility.

The followers of The Nancy School

The Nancy School, in its broader context, encompassed a loosely affiliated group of psychiatrists who embraced Bernheim’s principles and techniques. Notable figures among them included Albert Moll and Schrenck-Notzing in Germany, Kratft-Ebing in Austria, Bechterev in Russia, Milne Bramwell in England, Boris Sidis and Morton Prince in the United States, along with several others deserving recognition.

Sweeden

Otto Wetterstrand, a popular Swedish physician, treated 30–40 patients daily in Stockholm, often hypnotizing them in group settings. He ran a private hospital where former patients worked as nurses and used prolonged hypnotic sleep lasting 8 to 12 days as therapy.

His methods helped uncover deep emotional conflicts, a concept echoed today in trauma therapy Dubai. Wetterstrand’s work also contributed to early ideas about split personality, as patients under hypnosis sometimes revealed multiple identities.

In 1898, Otto Wolff adapted his method by using Trional, replacing hypnosis with medication.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, Frederik Van Eeden, conducted audacious experiments with hypnosis. He endeavored to teach French to a ten-year-old girl under hypnosis, a language she was unfamiliar with while awake. Subsequently, Van Eeden transferred this knowledge from her sleeping to waking state, allowing her to comprehend and speak French to her astonishment. In 1887, Van Eeden and Van Renterghem established the Institut Liebeault, a psychotherapeutic clinic in Amsterdam.

Switzerland

Switzerland saw the contributions of Auguste Forel, a professor of psychiatry in Zurich and director of the famous Burghölzli psychiatric hospital. Forel visited Bernheim in 1887 and swiftly became one of the leading experts in hypnotism. Similar to Liebeault and Bernheim, he achieved remarkable success in treating certain physical illnesses. Forel established an outpatient service for hypnotic therapy. Notably, his innovative application of hypnotism involved hypnotizing the hospital’s staff, not the patients. Male and female nurses volunteered to be hypnotized, and Forel suggested that they would sleep soundly in the wards for agitated patients, awakening promptly if any unusual or dangerous behavior occurred. This method reportedly proved quite effective.

The Influence of the Nancy School

Together, Liebeault and Bernheim paved the way for the Nancy School, revolutionizing the field of hypnotism and challenging conventional medical practices. Their contributions reshaped the understanding and application of hypnosis, leaving an enduring impact on the medical community. Bernheim’s clash with Charcot and his subsequent championing of Liebeault’s ideas marked a turning point in the understanding and practice of hypnosis.

The rise of the Nancy School brought about a shift in perspective, opening new ways for psychotherapy. Among the many visitors to Nancy, Sigmund Freud, spent in 1889 several weeks with Bernheim and the venerable Liebeault. He was intrigued by Bernheim’s assertion that posthypnotic amnesia was not as absolute as commonly believed. Through focused concentration and skilful questioning, Bernheim could elicit the recollection of the patient’s experiences under hypnosis. This insight was crucial for Freud for the development of psychoanalysis while refraining from hypnosis.

Around 1900, Bernheim enjoyed widespread recognition as Europe’s leading psychotherapist. However, within a decade, he faded into relative obscurity as other supposedly more contemporary figures gained prominence. Notably, Dubois in Berne emerged as a renowned figure, leading Bernheim to express bitterness over the perception that his own discovery had been “annexed” in 1871, akin to the German annexation of Alsace and Lorraine. Despite being a respectful disciple of Liebeault for many years, Bernheim now saw himself as the true pioneer of psychotherapy, with Liebeault serving as his precursor. Shortly before his death, Bernheim found solace in witnessing the return of his native Alsace to France. Visit us on Facebook for more updates and insights.