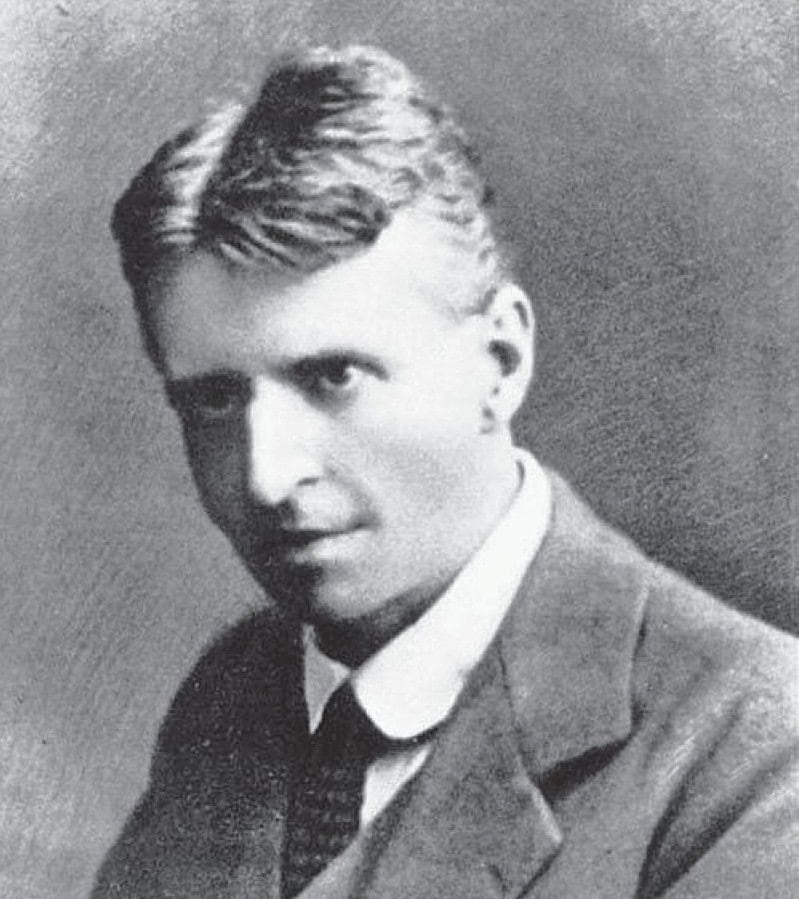

Otto Gross. Biography and Work. Introduction

Otto Gross, an Austrian psychoanalyst and anarchist, remains a largely unexplored figure in the annals of psychoanalytic history.

Despite his significant contributions to fields such as psychiatry, sociology, and literature, Gross has been overshadowed by contemporaries like Carl Gustav Jung.

In an era of burgeoning psychological inquiry, Gross’s ideas were radical, reaching the extreme of thought and overstepping the boundaries of psychoanalysis.

Otto Gross’s unconventional, and rebellious life style full of scandals, drug addiction and at the end mental insanity overshadowed his work and marginalization him within the psychoanalytic field.

But there was time that Gross was in high esteem within the psychoanalytical community. In one of his letter to Jung, Freud wrote:

“You are really the only one capable of making an original contribution; except perhaps for Otto Gross“

Freud/Jung Letters 1974, p. 126

In 1908, Jung wrote to Freud:

“in Gross I experienced all too many aspects of my own nature, so that he often seemed like my twin brother”

Freud/Jung Letters 1974, p. 156

This sidelining is reflective of a broader trend within the history of psychoanalysis. This approach to the history of psychoanalysis, reflects a pattern of the discipline purging its most radical innovators, similar to Gross, such as Wilhelm Reich or Erich Fromm.

This article aims to shed light on Gross’s life and his contributions to the development of psychoanalysis.

Otto Gross. Biographical Note

Otto Hans Adolf Gross was born on March 17, 1877, in the small Austrian town of Gniebing. He was the son of Hans Gross, a renowned criminology professor and pioneer of fingerprint analysis,

Gross’s mother seemingly completely submitted to her husband, foregoing her own life and barely noticeable as an individual. Otto, an only child, had a sheltered upbringing, attended private schools, and studied medicine in Graz, Munich, and Strasbourg, graduating in 1899.

Gross married Frieda Schloffer in 1903, and his network included influential sociologists like Max Weber.

Grosss’s Lifestyle Beyond the Norms

Gross frequented Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland, a hub for nudists, reformers, anarchists, pacifists, artists, and writers, where he hoped to further develop his ideas. By 1907, Gross had already made a significant impact on the intellectual scene in Germany and Switzerland. His radical thoughts on the liberation of the psyche and the critique of societal norms resonated with the anarchist movements and the art scene.

Otto Gross’s addictions, polygamous lifestyle and radical ideas increased the conflict with his father. Eventually, Gross senior, initiated Otto’s several hospitalizations in psychiatric institutions including the famous Burghölzli Hospital in Zurich.

Otto Gross’s Psychological and Social Background

Understanding Otto Gross’s life is impossible without considering his relationship with his father. Hans Gross who was a university professor of criminalistics at the University of Grass and pioneered criminology as an independent science. He was a well-known, strong-willed, and dominant figure, alien to the democratic rights.

His upbringing in a family dominated by a patriarchal father and a subservient mother influenced his believes and his rebellious actions against the oppressive structures of society and politics. This personal history led him to advocate for the emancipation of women, freedom in sexual relationships, and the dissolution of traditional family structures.

The Philosophical Influence

Philosophically, Gross was influenced by a spectrum of thinkers from Rousseau’s naturalism to Nietzsche’s critique of morality, and from Marx’s socio-economic analyses to the anarchist ideas of Proudhon and Kropotkin. His engagement with these ideas fuelled his critique of societal norms and his vision for a new society based on anarchistic principles.

Crossing Ethical Bondaries

Gross’s revolutionary ideas extended beyond theory into his personal and professional life, blurring the lines between personal liberation and professional practice. He experimented with living these ideals by forming unconventional relationships and communities, which became infamous.

Gross’s downfall in the psychoanalytic community was the consequence of his radical ideas and the societal discomfort they provoked. His life and work challenged the bourgeois values of early 20th-century European society, which valued family, hierarchy, and stable social roles. Gross, with his advocacy for a radical reordering of societal structures, became too much of a threat to these established norms.

Otto’s Final Years and Death

Despite these challenges, Gross’s intellectual contributions continued. He planned journals and schools aimed at exploring the psychological underpinnings of anarchism and continued to publish influential works. However, his life was a constant battle with drug addiction, societal rejection, and repeated institutionalizations.

Finally, in 1914, authorities declared Otto Gross to be mentally insane. His father, Hans Gross, who had long supported Otto financially, became his guardian. Tragically, Hans passed away a year later, leaving Otto destitute.

With his father’s death, Otto lost not only his financial support but also a symbolic adversary against whom he had often defined himself. Since then, Gross’s behaviour took on a distinctly infantile quality, sealing his fate. In February 1920, Gross’s struggles culminated tragically when he was discovered half-frozen and starving on the streets of Berlin. Days before his 43rd birthday, he died of pneumonia.

His death was barely noted in the psychoanalytic community. Wilhelm Stekel and Ernest Jones were among the few who acknowledged his contributions, albeit posthumously.

Otto Gros and His Early Psychiatric Career

His early work as a physician took him to South America as a naval doctor. During this journey, he began consuming cocaine, morphine, and opium, developing a drug addiction that haunted him throughout his life. Upon his return to Europe, he shifted his focus to psychiatry, working in Munich and Graz.

Deeply engaged in the emerging field of psychoanalysis, Gross crossed paths with significant figures like Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung. He published his early writings in the “Archive for Criminal Anthropology and Criminology,” founded by his father. Very soon Sigmund Freud recognized Gross as the most brilliant mind within the field of psychoanalysis, along with Carl Gustav Jung.

Gross’s Engagement with Sigmund Freud

Otto Gross met Sigmund Freud personally around the time he became a private lecturer in 1906. Gross was initially a strong supporter of psychoanalysis. However, over time, his work began to diverge significantly from Freud’s.

Gross was the first to recognize the social conditioning of psychoanalytic findings. Unlike Freud, who focused on the treatment of individual illnesses, Gross saw the role of psychoanalysis in the broader socio-political context. His perspective was that the psychological changes within individuals could not be fully understood without considering the environmental impact.

Gross’s insistence on integrating psychoanalysis with social critique first became evident at the First Psychoanalytic Congress in Salzburg in 1908. Gross believed that psychoanalysis should not only alleviate personal suffering but also challenge and transform the societal and political structures. However, Freud was reluctant to turn psychoanalysis into socio-political movement. He stressed out that their role was strictly clinical: “We are physicians, and physicians we want to remain. ”

After recognizing Gross’s ideas as a threat to the burgeoning psychoanalytic movement’s respectability, Freud maintained a distance from him. Gross’s presence at pivotal psychoanalytic gatherings like the Salzburg Congress was downplayed. His writings ideas were not credited in the psychoanalytic literature that followed.

Otto Gross and Carl Gustav Jung

The relationship between Otto Gross and Carl Gustav Jung deepened after Grosse’s admission to the Burghölzli Hospital following a mental breakdown caused by drug abuse. The admission happened on the recommendation of Sigmund Freud. The interaction of those two men is a fascinating study of intellectual encounter and clinical engagement.

Jung initially analyzed Gross, but later Gross turned the tables and analyzed Jung. This analysis marked the start of an intense analytical and personal connection that would leave an indelible mark on Jung’s life and work.

The fading of Gross’s influence in Jung’s later work and the minimal public acknowledgment of Gross’s impact can be interpreted through multiple lenses. Professionally, Jung found it necessary to distance himself from Gross, whose radical ideas and tumultuous life could undermine his reputation. On a personal level, the intense, albeit brief, relationship initiated Jung’s psychological transformation, insights and challenges.

Gross Contribution to Psychoanalysis

Gross thoughts on the defence mechanism of identification with the aggressor predated similar concepts later articulated by Anna Freud and others. His discussions on the integration of body and mind anticipated aspects of what would become psychosomatic medicine.

Gross advocated a concept of mutual analysis, where analyst and patient are engaged in a reciprocal therapeutic relationship, which we call today a “therapeutic alliance”. His ideas influenced Wilhelm Reich, who, despite not citing Gross, developed similar theories. Reich’s work on character analysis and the role of sexual repression in social organization echoes Gross’s earlier writings on the intersection of individual psychology and societal structure.

Otto Gross’s Innovative Ideas

Otto Gross left several titles, among them five monographs published between 1901 and 1920. He wanted to turn psychoanalysis into a socio-political movement mixed with anarchist concepts and the idea of sexual liberation.

This approach placed Gross decades ahead of his time, anticipating ideas that figures like Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse would later champion. Gross argued that the liberation of erotic potential was essential for both personal well-being and societal change. Such notion underpins what would later be known as the “sexual revolution.”

However, at the beginning of the 20th century, this concept was too radical for the psychoanalytic community. Freud resisted the idea of blending psychoanalysis with political activism.

Gross’s holistic view of human psychology rejected any dualism between mind and body, instead viewing them as expressions of a single biological process. This perspective anticipated later developments in areas like psychosomatic medicine and holistic health.

Gross criticized the model of psychoanalysis endorsed by Freud. He argued for a more engaged and relational approach to psychotherapy, opposing Freud’s more detached stance. This relational approach foreshadowed later developments in later psychoanalytic innovations that emphasized the interpersonal dynamics in therapy.

Missing Historical Approach to Psychanalysis

The obscurity surrounding Gross’s legacy is reflective of a broader historical amnesia within psychoanalysis. In the introduction to his book “A Most Dangerous Method”, containing in-depth research and high-grade of objectivism John Kerr wrote:

“Psychoanalysis continues to exhibit an unconscionable disregard for its own history. No other contemporary intellectual endeavour, from conventional biomedical research to literary criticism, currently suffers from so profound a lack of a critical historical sense concerning its origins”

Kerr 1993, p. 14

Revisiting Gross’s work, therefore, is not just about restoring a forgotten figure but about engaging with the repressed ideas and controversies that shaped the development of psychoanalytical theories. This verdict counts also for Jung’s work and its shadowy aspects.

The Otto Gross Archive

The recent resurgence in the study of Otto Gross, an overlooked figure in the development of psychoanalytic theory, marks a significant turning point in the appreciation and understanding of early psychoanalytic pioneers.

The establishment of the Otto Gross Society in 1998 and the subsequent creation of the Otto Gross Archive in London are developments that underscore an increasing academic interest in Gross’s contributions.

The archive boasts an extensive collection of original documents, texts, and multimedia in multiple languages, making Gross’s work accessible to a global audience. This inclusivity not only broadens the scope of Gross studies but also encourages a multifaceted exploration of his ideas and their relevance to contemporary psychoanalytic thought.

The publication of Gross’s collected works online, with translations and commentaries, facilitates access to his writings, highlighting the complex interplay of personal and ideological struggles that shaped the early psychoanalytic movement.

Otto Gross. Biography and Work. Summary

Otto Gross biography reveals a renegade pupil of Sigmund Freud, the enfant terrible of psychoanalysis, a sexual immoralist, genius, and psychiatric case. These traits highlight the complexity and contradictions of his personality.

As an Austrian psychoanalyst, Gross explored criminology, cultural criticism, Darwinism, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis. His ideas often challenged existing societal and psychoanalytic norms, not just academically but in how he lived his life, sometimes with disastrous effects on himself.

Gross’s work in psychoanalytic therapy questioned traditional structures within the field, leading to his marginalization. He also had interactions with notable figures like Otto Gross C.G. Jung, further reflecting his influence and the controversies surrounding his approaches.

Otto Gross remains a figure of both genius and tragedy, whose innovative thoughts on the human psyche continue to provoke interest and debate. Gross’s radical ideas challenged and expanded Jung’s psychological constructs, especially concerning paternal significance, psychological typology, and Jung’s concept of transference.

The exploration of Gross’s life and theories offers valuable insights into the cultural and intellectual climate of early 20th-century Europe. His ideas resonated with and influenced key figures in both psychoanalysis and literature, such as Freud and Jung, and even literary figures like Franz Kafka.

Rediscovering Otto Gross

Despite the profound implications of his theories, Gross’s contributions were largely overlooked during his lifetime and after his death in 1920. Despite his marginalization, his ideas had a lasting impact on the field of psychoanalysis and beyond. His life and work serve as a testament to the deeply intertwined nature of personal pathology and societal structure.

Today, the relevance of Gross’s work is undeniable. Modern psychoanalysis increasingly considers the impact of sociopolitical factors on individual psychology. Issues such as gender, sexuality, and the mind-body connection, which Gross was among the first to address, remain central to contemporary psychoanalytic discourse.

Sadly, Gross’s undeniable contribution to the development of psychoanalysis is overshadowed by his radical political views as an anarchist, by his drug addiction, by his life style full of scandals, and finally by his mental illness. His contributions to psychoanalytical theory and practice are as controversial as they are profound.

Sources

Bernd A. Laska, Otto Gross zwischen Max Stirner und Wilhelm Reich, In: Raimund Dehmlow and Gottfried Heuer, eds.: 3. Internationaler Otto-Gross-Kongress, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München. Marburg, 2003, pp. 125–162, ISBN 3-936134-06-5 LiteraturWissenschaft.de.

Heuer, Gottfried. Otto Gross, 1877-1920, Biographical Survey.

Gottfried M. Heuer: Freud’s „outstanding“ Colleague/Jung’s „Twin Brother“. The suppressed psychoanalytic and political significance of Otto Gross. New York 2017.

Kerr, John. 1993. A Most Dangerous Method: The Story of Jung, Freud, and Sabina Spielrein, New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1993, p. 11.

Maddox, Brenda, Freud’s Wizard: The Enigma of Ernest Jones, London: John Murray (Publishers), 2006, p. 55.

Gerhard M. Dienes, Ralf Rother: Die Gesetze des Vaters. Problematische Identitätsansprüche. Hans und Otto Gross, Sigmund Freud und Franz Kafka. Ausstellungskatalog. Böhlau, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2003, ISBN 3-205-77070-6.

Walter Fähnders: Die multimediale Präsenz von Otto Gross. In: Psychoanalyse & Kriminologie. Hans & Otto Gross – Libido & Macht. 8. Internationaler Otto Gross Kongress, Graz 14.–16. Oktober 2011. Hrsg. von Christian Bachhiesl, Gerhard Dienes, Albrecht Götz von Olenhusen, Gottfried Heuer. TransMIT, Marburg 2015, S. 314–337.

Martin Green: Otto Gross. Freudian Psychoanalyst, 1877–1920. Literature and Ideas. Edwin Mellen, Lewiston NY 1999, ISBN 0-7734-8164-8.

Emanuel Hurwitz: Otto Gross – Paradies-Sucher zwischen Freud und Jung. Suhrkamp, Zürich 1979, ISBN 3-518-03305-0.

Franz Jung: Dr. med. Otto Gross. Von geschlechtlicher Not zur sozialen Katastrophe. In: Günter Bose, Erich Brinkmann (Hrsg.): Grosz/Jung/Grosz. Brinkmann & Bose, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-922660-02-9, S. 101–155.

Jennifer E. Michaels: Anarchy and Eros. Otto Gross’ Impact on German Expressionist Writers. Peter Lang, Frankfurt u. a. 1983, ISBN 0-8204-0000-9.

Michael Raub: Opposition und Anpassung. Eine individualpsychologische Interpretation von Leben und Werk des frühen Psychoanalytikers Otto Gross. Peter Lang, Frankfurt u. a. 1994, ISBN 3-631-46649-8.