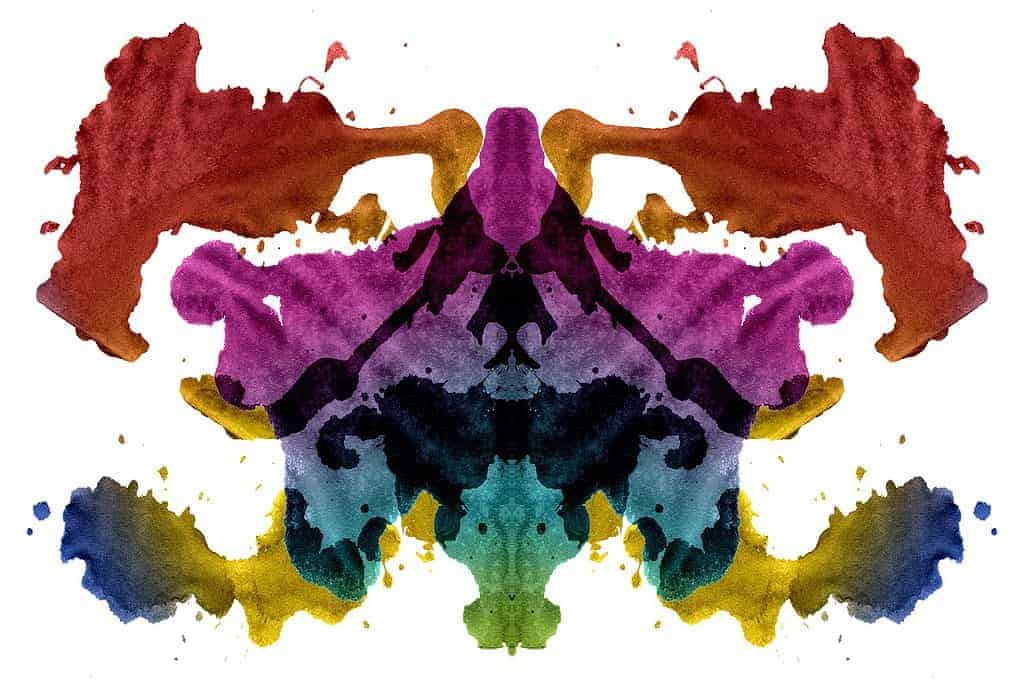

The Rorschach Test, also known as the Rorschach Inkblot Test, is a projective psychological assessment. It was developed by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach in 1921 and gained widespread popularity in the 1960s. During that era, it served as a common tool for assessing cognition and personality as well as for diagnosing mental health disorders.

In 1918, Rorschach began experiments with 15 inkblots. After extensive revisions, Rorschach reduced the number to 10 inkblots shown to participants in a specific sequence. He asked the subjects, “What might this be?” while presenting each inkblot.

Rorschach’s images were not random smears but carefully chosen and designed figures. The responses to the Inkblot test help identify subjects’ perceptive abilities, intelligence, emotional characteristics, and personality traits. A century later, these 10 inkblots are still used for psychological evaluations.

For Rorschach’s test assessment in Dubai, contact our specialized psychologists at CHMC:

Call CHMCRead more about test methods

- Psychometric Testing

- History of Psychological Testing

- IQ Test

- Personality Test. Millon Inventory

- Myers-Briggs Test

- C.G. Jung’s Word Assosiation Test

Because of Rorschah’s premature death, he was not able to develop for the test a standard evaluation tool. This happened much later, as in 1974 John Exner introduced the Rorschach Comprehensive System (RCS), a standardised manual for the Inkblot Test evaluation.

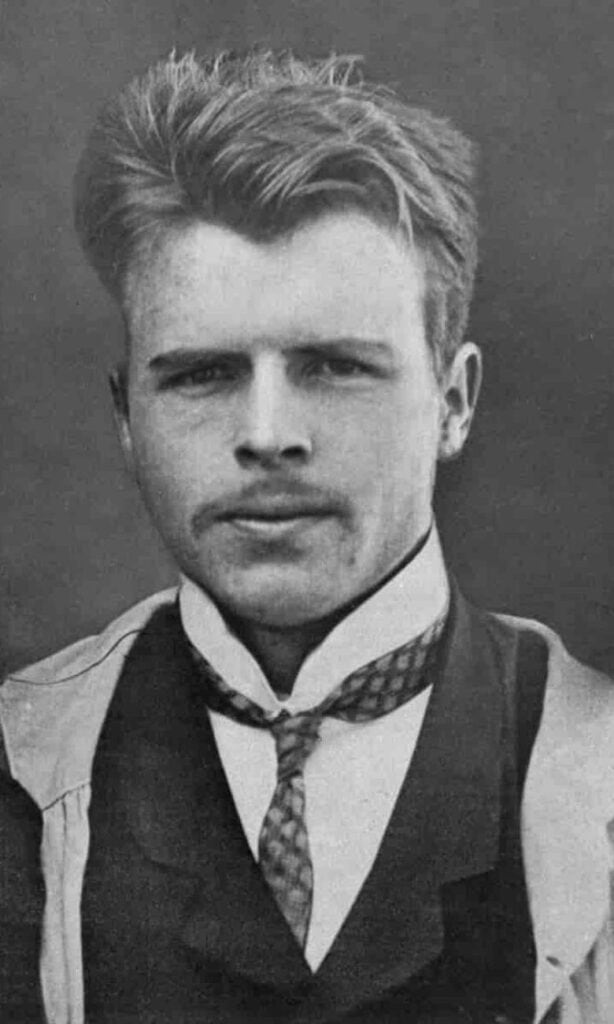

Hermann Rorschach. Biographical Note

Hermann Rorschach (born November 8, 1884, Zürich—died April 2, 1922, Herisau) was a Swiss psychiatrist. He was the eldest son of an art teacher and considered himself to be an artist. He grew up in a home filled with intellectual, artistic, and cultural stimulation, as described by Henri Ellenberger: “in an atmosphere of extraordinary intellectual, artistic, and cultural concentration.”

As he neared high school graduation, Rorschach faced a pivotal decision between a career in science and one in art. Finally, he decided to pursue a scientific path and enrolled in 1904 at the Academie de Neuchatel to study geology and botany but soon switched to the medical school at the University of Berne.

He pursued medical studies in Zurich, Nuremberg, Bern, and Berlin, eventually specializing in psychiatry.

Rorschach’s professional interests extended beyond psychoanalysis to the study of Swiss cults and the role of art and drawing in understanding personality.

During and after his studies, Rorschach interacted with prominent members of the Swiss psychoanalytic community, including Carl Jung. At that time Jung developed his Word Association Tests tapping into individual’s unconscious complexes. Rorschach himself experimented with similar techniques.

Studies and Early Academic Career

His studies took him to Zürich, Berlin, and Nürnberg, culminating in his 1909 graduation from the University of Zürich. In 1912, he wrote his doctoral dissertation under the psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler.

In 1910, Rorschach married Olga Stempelin, his Russian classmate from medical school. He left his position at a Swiss mental asylum in late 1913. He moved to Russia with his wife, where he worked at a private clinic. However, by July 1914, Rorschach had returned to Switzerland, becoming assistant director at a regional asylum.

His wife, detained in Russia due to the outbreak of World War I, rejoined him in Switzerland in the spring of 1915. According to her, Hermann returned to Switzerland because “in spite of his interest in Russia and the Russians, he remained a true Swiss, attached to his native land… He was European and intended to remain so at any price.”

Rorschach. The Psychoanalyst and Researcher

Rorschach practiced Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis but did not follow Freud’s dogmas rigidly. He promoted psychoanalysis in Swiss medical circles. The first 2 decades of the 20th century were a period of the most dynamic and fruitful development and research on psychoanalysis and what we call today “in-depth” psychology. In 1919, Rorschach’s contribution to the psychoanalytical movement was reworded, and he was elected vice president of the Swiss Psychoanalytic Society.

He studied with Carl Gustav Jung, and was inspireder by his word association test. Jung’s experimental method was the first scientific proof supporting Freud’s psychoanalytic theory. Rorschach was influenced by Jung’s methodology, recognizing the unconscious mechanism involved in the association process.

Rorschach continued his work as a psychiatrist at a remote psychiatric asylum in Herisau, Switzerland. In 1917, he invented the inkblot method with the focus of exploring mental health disorders. In 1921, he published “Psychodiagnostics,” explaining his inkblot test methods and experimental findings.

Rorschach died prematurely in 1922, aged 37, from untreated peritonitis. He left behind a wife, two children, and his groundbreaking but incomplete research.

Rorschach’s Development of Inkblot Test

Rorschach’s fascination with inkblots emerged during his high school years. He loved a game called Klecksography (Blotto), where he created inkblots and wrote stories about them. His friends even nicknamed him “Klecks,” the German term for inkblot.

Klexography, involving ink and folded paper, inspired him to use the method as a diagnostic tool. In 1918, Rorschach began experiments with 15 inkblots, asking subjects, “What might this be?” Later, he reduced the number of inkblots to 10. To develop his test, Rorschach conducted 100 studies using inkblot designs with mirror symmetry.

These inkblots were not random; they were meticulously crafted and revised in every detail. He tested his designs on hospitalised adolescents and people with schizophrenia. From their answers, he believed he could deduce mental illnesses and personality traits.

In 1921, Rorschach published in a monograph “Psychodiagnostics” the results of his studies on 300 mental patients and 100 others, introducing the Inkblot Test. He called the test the “psychological X-ray.” Influenced by Freud, he understood that the perception and interpretation of the blots are unconscious, pointing to the hidden contents of the psyche.

Rorschach’s Predecesors on Inkblot Research

Rorschah was not the first scientist who used inkblots. Already in 1895 Alfred Bienet working at Salpêtrière under the famous psychiatrist Jean-Martin Charcot, experimented with this method in his early testing on children in the French school system to measure visual imagination.

He was also inspired by Justinius Kerner’s 1857 book Kleksographien, which featured poems inspired by inkblot images. Kerner’s work, created by folding inked paper, was well-known in German-speaking countries and likely influenced Rorschach.

In 1917, Rorschach discovered the work of Szyman Hens, an early psychologist, who explored his patients’ fantasies using inkblots. He was also familiar with Carl Jung’s word-association test. He was highly interested in optical illusions and their psychological implications. While living in Russia, he collected visual puzzles published in newspapers and was fascinated by the ambiguity of such images and their interpretation by viewers.

Rorschach saw his work as a beginning and warned against hasty interpretations. Because of his premature death he left the Inkblot Test unfinished not developing any standirized interpretation guidlines.

Rorschach’s Late Recognition

Rorschach’s work on Inkblot Test, he described in the monograph “Psychodiagnostics,” was not a success during his lifetime. The text was written in scientific language, making it unaccessible for lay readers.

Rorschach himself was a psychoanalyst but did not consider his test part of this framework. He understood his test’s methodology as being located in the “grey area” between two psychological schools. The Inkblot Test was criticised by behaviourists for not being enough scientific, leaving the examiners too much space for subjective interpretations; on the other hand, the psychoanalysts rejected the test for its too structured nature.

Despite the initial lack of recognition, Rorschach’s work laid the foundation for a significant field in psychological assessment. His test and its interpretation have since sparked a global effort among psychologists. As Rorschach himself wrote, his goal was to explore “humans’ capacity for experiencing,” a vision that continues to influence the field today.

Metodology of Rorschach Test

The Rorschach Inkblot Test comprises 10 symmetrical inkblots, some in various colours—black, red, or both. Rorschach developed a coding system assigning scores to “whole,” “detail,” and “motion” responses. The examiner sits beside the subject, concentrating on his interpretations. Participants view each inkblot individually. The test comprises several steps:

- Presentation: The examiner provides one card at a time, asking, “What might this be?”

- Response: The tested person has the freedom to interpret each image as he wishes, taking time and offering multiple responses. Card orientation is flexible.

- Recording: the examiner diligently records everything the subject says, including timing, card position, and emotional expressions.

- Confirmation: After the initial round, the examiner revisits each inkblot. The objective is not new information but a deeper understanding of the subject’s perspective.

During the test, the examiner asks the following questions:

- Do you see the whole picture, or do you get stuck on smaller elements?

- Can you easily switch focus between parts, or do you struggle with flexibility?

- Do you perceive motion and life in the images or see only static, cold forms?

- Do you follow or defy the norm?

Interpretation of Rorschach Test

Rorschach did not provide detailed instructions for interpreting the test, leaving room for different approaches. The challenge lies in the freedom the test gives therapists, leading to varied conclusions. Identical responses can result in differing interpretations depending on the evaluator’s perspective. Rorschach was aware of more refinement needed to standardise his method, which he couldn’t fulfil because of his premature death.

Before 1970, the Rorschach test had multiple scoring systems—five, to be exact—that were so different from each other they essentially represented five distinct versions of the test. This lack of standardisation caused confusion and inconsistency.

Exner Scoring System of Rorschach Test

Recognising the need for a unified approach, John Exner developed a new scoring system in the 1960s, which he fully introduced in 1974. Known as the Exner Scoring System or the Rorschach Comprehensive System (RCS), it combined the best elements of the earlier methods into one cohesive framework. The Exner Scoring System adopts, for instance, an area coding method that categorises the parts of the inkblots people choose to focus on. Additionally, it incorporates the concept of “form quality,” which dates back to Hermann Rorschach himself.

The Exner system focuses on how individuals process, interpret, and think about the images presented in the inkblots. It evaluates responses by looking at factors such as how clearly they match the inkblot (its “form quality”), the location on the blot that was referenced, and the type of reasoning or perception involved in creating the response. After collecting and scoring the responses, examiners compile the results into a structural summary.

The Exner system has been extensively tested and is considered highly reliable, particularly because it reduces variation between different examiners’ interpretations.

Uses of Rorschach Test

The Rorschach Inkblot Test ranks among the world’s renowned projective psychological assessments. Psychologists deploy it to scrutinise cognition, personality, and emotional states. This test also helps to uncover hidden thought patterns and distinguish between individuals with or without, for example, a latent psychosis.

At the beginning, the test was designed to detect mental health disorders like schizophrenia. Over time, it expanded to assess personality, emotional disorders, and intelligence. Standardised with the Exner system, it allows to assess effectively along with psychosis also depression, anxiety, and give insight into an individual’s personality. The test can be administered to any person above 5 years of age.

In the corporate world, organisations use the test to assess attributes like creativity, intelligence, and temperament, giving insights into candidates’ suitability for employment. The Inkblot test can be used in correctional facilities and for forensic evaluation of criminals to assess their prognosis, for example, for rehabilitation and reintegration purposes, evaluating the subject’s societal adaptation skills.

Popularisation of Rorschach Test

When Rorschach died suddenly in 1922, his test was abandoned. In Switzerland, it was mainly used for job interviews and vocational testing. In Germany, where Rorschach had angered prominent psychologists, the test never became popular.

However, the test spread globally. In 1925, Yuzaburo Uchida discovered “Psychodiagnostik” in a Tokyo bookshop. By 1929, the inkblots were introduced to Japanese psychology and remain Japan’s most popular test.

Each country’s adoption of the test has its own unique historical trajectory. The Rorschach test is also prominent in Argentina, gaining ground in Turkey, but marginal in Russia. In Australia, it is rarely used, while in Britain, it has fallen completely out of favour.

In the United States, the test saw its most dramatic rise and deepest cultural integration. During the mid-century peak of Freudian psychoanalysis, it was called the “X-ray of the unconscious.” The test promised faster, cheaper insights compared to endless talk therapy sessions. However, its misuse grew; with expectations, it could read thoughts or uncover hidden truths.

The test inspired global imagination, appearing in noir films, perfume ads, and even music videos. In the 1970s, John Exner formalised the test with norms and reproducible, statistics-based methods. This standardised system proved effective in detecting suicide risks, psychosis, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

For the correct evaluation, the Rorschach test must be paired with a psychological interview. It helps assess patients’ challenges and strengths while facilitating productive, therapeutic conversations.

Inkblot Test’s Use in Military and Politics

The test was used by U.S. forces during World War II for screening prospective pilots and soldiers, identifying suitable candidates. After WW II, the Rorschach Test was applied for assessing the Nazi war criminals. Unfortunately, the test results were lying forgotten in the US archives until their recent discovery and publication by Joel E. Dimsdale.

Between 1941 and 1968, researchers published around 5,000 articles on the test worldwide. The inkblots were interpreted by everyone, from Blackfoot Native Americans to Ifaluk islanders in Micronesia.

Abuse of Rorsch Test during the Vietnam War

During the Cold War, this psychological curiosity reached a low point in its ethical application. The U.S. Department of Defence sent psychologists to war-torn Vietnam to “win hearts and minds.” In 1966, Walter H. Slote, a Columbia University lecturer and psychotherapist, spent seven weeks in Saigon. His mission was to study the “Vietnamese personality” using psychoanalysis and the Rorschach Test.

Slote’s work ignored obvious political, historical, and military reasons for Vietnamese resentment of the U.S. Yet, it was well-received by Americans: The Washington Post called it “hypnotically fascinating.” Saigon officials described his findings as “extraordinarily insightful and convincing.”

These wild, misguided uses of the test eventually faced widespread and justified criticism. By the late 1960s, inkblots fell out of favour in many countries. In Britain, the test never recovered, but in the U.S., it was redescovered during the 1970s.

New approaches emphasised measurable outcomes, but controversies about the test’s validity persisted. However, the enduring use of the same ten cards for over a century has amassed vast data and proved the Inkblot Test usability.

Assessing Nazi War Criminas with Inkblot Test

After World War II, the Allies held the Nürnberg trials to prosecute Nazi leaders for war crimes. Joel E. Dimsdale, a psychiatry professor, revisits these events in his book “Anatomy of Malice: The Enigma of the Nazi War Criminals.”

Dimsdale’s fascination with the Nazi perpetrators began in 1974, when he met one of the Nürnberg executioners. He was intrigued to learn that the Nürnberg defendants underwent Rorschach Inkblot Tests. This discovery led him to the trial archives and to the work of the psychologists and psychiatrists who assessed the prisoners. The psychologist Gustave Gilbert and the psychiatrist Douglas Kelley had unparalleled access to the Nürnberg defendants, spending hours listening to and testing them. The main testing method was the Rorschach Inkblot Test.

Dimsdale focused on four key Nazi leaders in his analysis:

- Robert Ley, head of the German Labor Front, who suffered brain damage from an accident and committed suicide before his trial.

- Hermann Göring, a powerful Nazi leader and founder of the Gestapo, who was both charming and ruthless. Göring took his own life hours before his scheduled execution. His younger brother, Albert, opposed the Nazi regime and helped rescue Jews.

- Julius Streicher, the publisher of the anti-Semitic newspaper Der Stürmer, was despised even by his fellow prisoners.

- Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy until 1941, spent the rest of his life in prison, dying by suicide in 1987 at the age of 93.

Inkblot Test Results of WW II Criminals

The Rorschach test in UAE has long been a tool for psychological analysis, but its significance was highlighted when psychologist Molly Harrower revisited the tests years after they were conducted. Along with a panel of experts, Harrower mixed the Rorschach psychological test results with those of clergy and mental patients. Surprisingly, the experts could not distinguish the Nazis from other groups. This challenges the comforting notion that Nazi leaders were uniquely evil and instead suggests that under certain conditions, ordinary people can commit horrific acts. The Rorschach test in Dubai has since become an essential tool in uncovering deeper psychological insights, and the Rorschach mental health test in Dubai can offer a clearer understanding of one’s inner psyche.

Based on intense interviews and test results, Douglas Kelley, the involved psychiatrist, depicted Nazism as a cultural and social phenomenon rather than a psychological anomaly. He believed the Nazis were not inherently monstrous but shaped by their circumstances. In his view, they were egocentric, aggressive, and morally bankrupt—but not fundamentally different from many high-ranking corporate executives.

One chilling statement came from Rudolf Hess during his interviews: “I am entirely normal. Even while I was doing the extermination work, I led a normal family life… I was just obeying orders. I didn’t personally murder anybody.”

Dimsdale concludes that the results of psychological testing of Nazi war criminals have profoundly influenced how we understand the roots of malice and human evil. It underscores the uncomfortable truth that the potential for violence exists in all of us.

Rorschach Inkblot Test. Summary

It’s vital to clarify that the Rorschach test, though intriguing, isn’t a mystical “X-ray of one’s unconscious.”. It’s a well-supported projective assessment, backed by ten decades of research since Hermann Rorschach’s 1921 publication.

Initially, Rorschach didn’t call it a “test” but considered it a perception experiment, echoing Jung’s word association experiment. He investigated the association process of individuals exposed to standardized inkblots. At the beginning, the test was thought to be just a scientific experiment. However, later Rorschach recognised its larger clinical and diagnostic potential.

Today, clinicians employ the Exner system to assess the responses. The Exner Scoring System unified the former fragmented evaluation methods into a more scientific and reliable tool. After all cards are presented and responses coded, an interpretative report compiles the patient’s scores. Interpretation considers not only the content of observations but also how the participant analyses the images. Does the participant focus on details or see the image as a whole? Do they emphasise colours or shapes? Do they perceive movement or only static forms?

The Rorschach Test helps in identifying and diagnosing mental health disorders, such as schizophrenia, along with serving as a common tool for assessing cognition and personality. It remains in use across diverse settings like hospitals, schools, and courtrooms, providing valuable insights into individual’s personalities and their underlying motivations.

The Rorschach test is still conducted today exactly as it was 100 years ago.

Rorschach Test Assessment Sessions at CHMC

At CHMC, German Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, we provide Rorschach assessment in 3 sessions:

- The Intake Session: Duration: 90 minutes

- The Assessment session: Duration: 90 minutes

- The feedback/recommendation session: Duration: 60 minutes

For further information about the Rorschach test, contact our clinic in Dubai:

Call CHMCSources

The Life and Work of Hermann Rorschach (1884–1922), by Henri Ellenberger, 1989, Routledge, ISBN9780203772034

Rorschach H (1927). Rorschach Test – Psychodiagnostic Plates. Hogrefe. ISBN 978-3-456-82605-9.

Butcher, James Neal (2009). Oxford Handbook of Personality Assessment (Oxford Library of Psychology). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-19-536687-7.

Exner, J.E. (1969). The Rorschach systems. Grune & Stratton.

Pichot P (1984). “Centenary of the birth of Hermann Rorschach. (S. Rosenzweig & E. Schriber, Trans.)”. Journal of Personality Assessment. PMID 6394738.

“About the Test”. The International Society of the Rorschach and Projective Methods. Archived from the original on 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

Anthony D. Sciara, Barry Ritzler. “Rorschach Comprehensive System: Current issues”. Rorschach Training Programs, INC. (RTP). Retrieved 7 December 2013.

James M. Wood, M. Teresa Nezworski, Scott O. Lilienfeld, & Howard N. Garb: The Rorschach Inkblot Test, Fortune Tellers, and Cold Reading Archived 2012-03-12. Skeptical Inquirer magazine, Jul 2003.

Garb HN (December 1999). “Call for a moratorium on the use of the Rorschach Inkblot Test in clinical and forensic settings”. Assessment. PMID 10539978

Wood JM, Nezworski MT, Garb HN (2003). “What’s Right with the Rorschach?”. The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice.

Weiner IB (1999). What the Rorschach Can do for you: Incremental validity in clinical applications. Assessment 6.

Exner J.E., Wylie J. (1977). “Some Rorschach data concerning suicide”. Journal of Personality Assessment. 41. PMID 886425.

“Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct”. American Psychological Association. 2003-06-01. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

Koocher GP, Keith-Spielgel P (1998). Ethics in psychology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509201-1.

Radford B (2009-07-31). “Rorschach Test: Discredited But Still Controversial”. Live Science. Imaginova Corp. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

Exner JE (1995). The Rorschach: A Comprehensive System (Vol 1: Basic Foundations). New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-55902-3.

Gacano CB, Meloy JR (1994). The Rorschach Assessment of Aggressive and Psychopathic Personalities. Hillsdale, New Jersey Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN 978-0-8058-0980-0.

Rorschach H (1998). Psychodiagnostics: A Diagnostic Test Based on Perception (10th ed.). Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-3-456-83024-7.

Weiner IB (2003). Principles of Rorschach interpretation. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN 978-0-8058-4232-6.

Anatomy of Malice: The Enigma of the Nazi War Criminals, May 24, 2016, by Joel E. Dimsdale Publisher: Yale University Press (May 24, 2016) ISBN-10: 0300213220