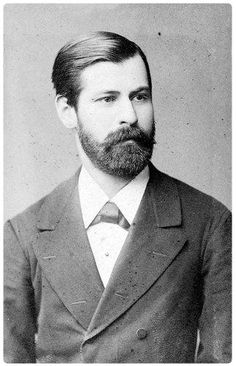

Sigmund Freud biography (6 May 1856–23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud’s ideas and his concept of the human psyche can be understood only in the context of his life and the time period when he lived.

The end of the 19th century was an era of revolutionary ideas in arts, science, and politics. This tumultuous socio-political movement changed the old-world order and found its climax in the horrors of World War I.

Freud’s epochal achievement was the development of psychoanalysis and its application as the first effective method of psychotherapy. In 1917, Freud published his Lectures on the Introduction to Psychoanalysis, in which he presented psychoanalysis not only as a method but also as a comprehensive theory of personality. This marked a key moment in Sigmund Freud life and discoveries that shaped modern psychology.

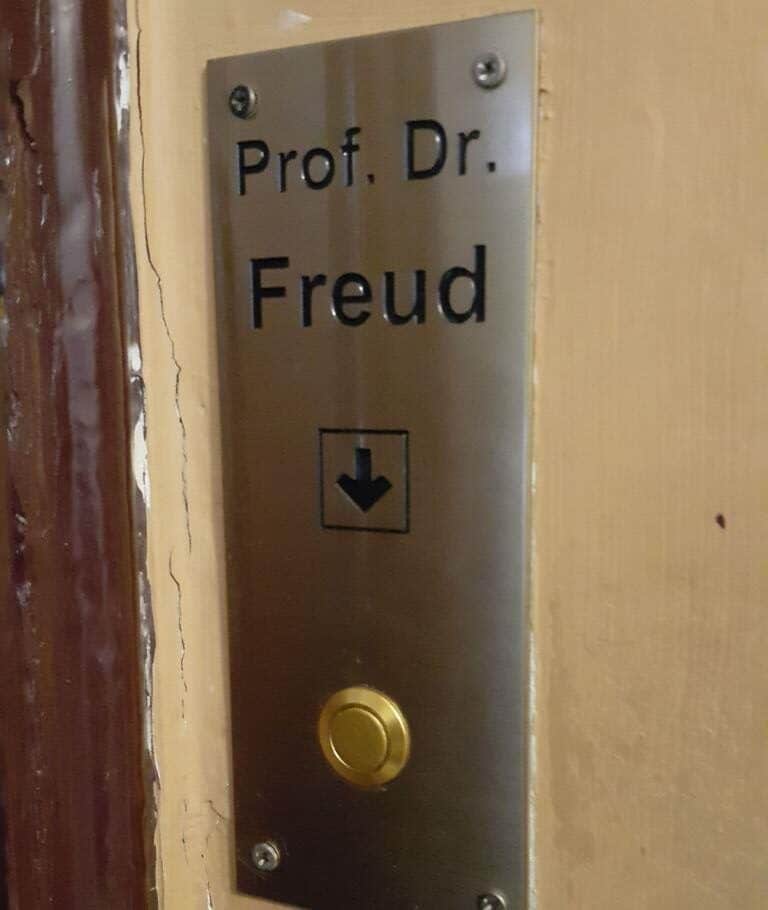

Starting in 1902, a group of colleagues interested in psychoanalysis, known as the Wednesday Society, began meeting in Freud’s practice rooms on Berggasse 9 in Vienna. By 1908, this group became the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. In 1910, the International Psychoanalytic Association was founded, marking the beginning of sigmund freud influence on psychology worldwide.

This short biography of Sigmund Freud introduces the reader to the period between the late 19th and beginning of the 20th century and expands on the development of psychoanalysis.

Read more about Sigmund Freud:

- Sigmund Freud and C.G. Jung

- Defence Mechanism in Psychodynamic Therapies

- What Is Split Personality?

- Sigmund Freud. Studies on Cocaine

- In Memory of Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud. Family Background

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg (now Pribor, in the Czech Republic), a small town in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was the first of eight children. Sigmund Freud’s father, Jacob Freud, was a wool merchant from a Hasidic family. By the time Sigmund was born, Jacob was already 40 years old and 20 years senior to his mother, born Amalia Nathanson. Sigmund had two half-brothers from his father’s first marriage, who were about 20 years older than him. However, they left Austria during Freud’s early childhood to seek a livelihood in Manchester.

Since Freud was Jewish, Sigmund’s early experiences were largely those of an outsider in the Catholic community. The Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916) emancipated the Austrian Jews, liberated them from ghettos, gave them the same rights as the other citizens, and opened new opportunities for the Jewish population.

In this time many Jewish families moved from the other parts of the Empire, especially from the rural areas in Galicia (today’s part of Ukraine and South Poland), settling in Vienna and hoping for a better life. Struggling with financial difficulties, Freud’s family left Freiberg in 1859, first for Leipzig in the German Empire and then for Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They settled in Leopoldstadt, a district of Vienna mostly populated by Jewish inhabitants, living at the beginning in cheap accommodations.

Freud’s School Years

After the age of 9, Freud joined the local primary school. From 1866 he continued his education at Sperl-Gymnasium in Leopoldstadt (in Europe gymnasiums prepare for university entrance), which at that time was one of the best schools in Vienna.

Higher education in Europe at the end of the 19th century was influenced by the culture of antiquity. Apart from mathematics, history, and the natural sciences, the students learned Greek, Latin, and the history of antiquity. The influence of this classic education will find its echo in Freud’s psychoanalytical theory in terms based on Greek mythology, such as the Oedipus complex.

Freud was an excellent student. He passed his final exams with distinctions. His family was aware of his special scientific genius from an early age, allowing him to have a room to himself while his siblings shared theirs. Sigmund was undoubtedly his mother’s favorite child, who called him “my golden Sigi.” When Sigmund studied, his sister Anna was not allowed to play piano.

Freud lived with his parents until the age of 27, as was the custom at that time.

Studies at Vienna University

In 1873, at age 17, Freud was admitted to the medical faculty at the University of Vienna. He finished the university as a doctor of medicine not until 1881. Because of his broad interests, it took him nine years to get his degree in medicine. He participated in neurophysiological research under Ernst Brücke, visited lectures in philosophy under Franz Brentano, and in zoology under Carl Claus, a strong supporter of Darwinism.

After finishing university, Freud continued the research at the University of Vienna in the field of neuropathology in the laboratory of Ernst Brücke. His research was dedicated to studies on the nervous tissue of vertebrates. In 1885, he completed his research, acquiring habilitation in neurology.

Freud’s Marriage

Sigmund Freud met his future wife, Martha Bernays, in April 1882. Sigmund was 26, and Martha was 21. It must have been love at first sight for both of them. Premarital sex was out of the question for the traditionally raised couple. They secretly got engaged just two months after meeting. However, they had to wait over four years before Martha became his wife in September 1886. Four years of courtship and suffering, of hope and struggle, mostly spent apart. Their love remained largely one of letters.

Freud destroyed his records and letters multiple times in his life. Only Martha’s and the family’s letters were spared. Even in exile, the “engagement letters” were saved. After Freud’s death in 1939, Martha considered destroying them. When Ernest Jones used them for Freud’s biography, they became legendary. They revealed a completely different Freud. However, Martha’s letters remained unpublished until, according to Anna Freud’s will, they were released to the public first in 2000.

Freud in Love

Martha’s published letters revealed for the first time her personality: a young woman, just over 20, educated, intelligent, and initially shy in her words. Yet she was confident enough to handle her passionate and temperamental fiancé.

Freud was lovesick, crisis-ridden, and emotionally exhausted. At 26, he was completely inexperienced in love, going through a delayed adolescence, plagued by doubts and insecurities. His extreme poverty made him swing between grandiosity and inferiority. This turned him into a grumbling, tyrannical, and somewhat pathetic lover. His pathological jealousy tormented him and led him to cruelty.

Martha, on the other hand, was rational and level-headed. She was a strong-willed young woman, showing clear boundaries to her emotionally unstable and immature fiancé. But Martha also restored his faith in himself. She gave him hope and the strength to work when he needed it most.

Martha was not a conventional beauty. Nature had given her beautiful eyes and a noble forehead.

But her mouth and nose were strikingly expressive, almost masculine. In one letter, Freud reassured her about her imperfect looks:

“And don’t forget, my only dear girl… beauty lasts only a few years, but we want to endure a lifetime together. When youth’s smoothness and freshness fade, beauty remains where kindness and intelligence shape the features, and then my little Martha will surpass the others.”

Living in Poverty

Both were poor. Freud constantly worried about his sick mother and five sisters. His father, Jacob Freud, a wool merchant, never had stable work in Vienna. Martha’s financial situation was hardly better. Her father, Berman Bernays, was an unlucky businessman. He was even sentenced to prison for delayed bankruptcy.

All Freud and Martha had to live on was their love. Few documents are as heartbreaking as Freud’s expense records. Even a piece of chocolate he bought out of hunger was listed.

Martha and Sigmund Freud’s Wedding

Since Martha could no longer wait, she wrote a letter on August 3, 1884, saying she would return to Vienna and take a job as a nanny. For Freud, this letter was proof of her love, but the idea also hurt and embarrassed him. To end Martha’s suffering and likely prevent her from returning to Vienna penniless, her aunt provided a generous financial contribution. Other relatives followed suit, making the wedding possible.

On September 13, 1886, Sigmund Freud and Martha Bernays were married at Wandsbek Town Hall. The next day, Rabbi Hanover conducted the religious ceremony at the Wandsbek Synagogue. According to Austrian law, a civil marriage alone would not have been officially recognized.

The “enlightened and non-religious” Jew Sigmund Freud had to comply. Fourteen people attended the ceremony, including Martha’s uncle Elias, from whom Freud had learned the prayer formulas the night before. The wedding dinner was held at Hirschel’s Hotel on Wexstraße. Their honeymoon took them to Travemünde on the Baltic coast, near Lübeck.

Martha’s Life with Sigmund Freud

In April 1886, Freud opened a private practice at Berggasse 19. It also became the family home. After the wedding, one of Freud’s conditions was that Martha abandon all religious customs.

Kosher cooking and Jewish holidays were forbidden in the Freud household. She accepted this.

Their marriage turned out to be a remarkably peaceful one. After Freud’s death, Martha found comfort in the thought that “in 53 years of marriage, there was not a single angry word between us.”

The couple had six children: Mathilde Freud (1887–1978), Jean Martin Freud (1899–1967), Oliver Freud (1891–1969), Ernst Freud (1892–1966), Sophie Freud (1893–1920), and Anna Freud (1895–1982).

Martha Freud passed away in 1951. She was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium, and her ashes were placed in Freud Corner, in the same ancient Greek funeral urn that holds her husband’s ashes.

Freud Studies at Salpêtrière in Paris

At that time, Charcot was one of the most famous physicians in Europe. Charcot was trained as a neurologist but dedicated his attention to hypnosis. Freud witnessed Charcot inducing pseudo-epileptic, so-called hysterical seizures, in patients through hypnosis. This strengthened Freud in his assumption that the triggers of certain diseases are not of a physical but of psychological origin.

The term “hysteria” derives from the Greek word “hystera,” which means “womb.” In the 19th century, hysteria, which means “over-excited behaviour,” was exclusively diagnosed in women. By demonstrating that traumatic experiences can lead to hysteria in everyone, Charcot contradicted this hypothesis for the first time.

Freud’s Early Scientific Studies

Beginning in 1881, Freud joined the Vienna General Hospital as a physician, where he worked in different departments. In parallel, he conducted studies in the field of neurology. His research created one of the cornerstones for the discovery of neurons. He published papers on aphasia.

His other interest was psychopharmacology. In 1884, Freud published a paper, “On Coca,” from today’s standpoint a controversial study. However, at this time, cocaine was a newly extracted drug with stimulating properties. Freud assumed that it could be used for the treatment of alcohol and drug addiction. After having discovered the addictive nature of cocaine, he abandoned the studies on cocain.

In 1885 he got a grant from the Austrian government, which allowed him to travel to Paris and to participate in the lectures of Jean Martin Charcot in the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris. Salpêtrière, at that time, was the leading hospital in the field of neuroscience. Freud stayed in Paris from October 1885 to February 1886.

The Interpretation of Dreams

In his letters to Fliess, Freud reported, among other things, about his dreams and fantasies. By now he was aware that dreams are much more than incoherent visual fantasies appearing during sleep. Much more, they opened up to him as a way into the deeper layer of the psyche. He wrote, “The dream is the royal way to our soul.”

In 1900, Freud published “The Interpretation of Dreams,” which he considered to be one of the most important works of his life. To justify and explain his theories, he went into the stories of his anonymous patients as well as his own dreams.

Development of Psychoanalysis

In 1923, Sigmund Freud published his work “The Ego and the Id.” The famous model described therein assumes that the human psyche is composed of the Id, the Ego, and the Superego.

The Id represents the unconscious, that is, drives, needs, and affects. When a person is born, they initially consist solely of the Id: For a baby, it is exclusively about asserting its innate drives, such as obtaining food and being touched.

The Ego corresponds to one’s conscious thinking and conveys to a person the image they have of themselves. The Ego operates according to the reality principle instead of the pleasure principle of the Id.

The Superego, on the other hand, is, according to Freud, the psychic structure in which social norms and values are anchored—that is, everything that has been imparted to a person through upbringing and external influences.

Importance of Freud’s Discoveries

Sigmund Freud was well aware of the importance of his discoveries to science. On April 28, 1885, the 28-year-old Sigmund Freud gathered all his correspondence, notes, and manuscripts and threw them into the stove. Then he sat down and wrote to his beloved fiancée and future wife, Martha:

“I have just carried out a decision that will deeply affect a group of men who have yet to be born. Since you won’t be able to guess whom I mean, I will tell you: my biographers. I have destroyed all my diaries from the past fourteen years… only personal letters have been spared. Yours, my dearest, were never in danger.

Let the biographers rage—we mustn’t make it too easy for them. Let each one believe that his version of the hero’s development is the right one; I am already amused at the thought of how mistaken they will be…”

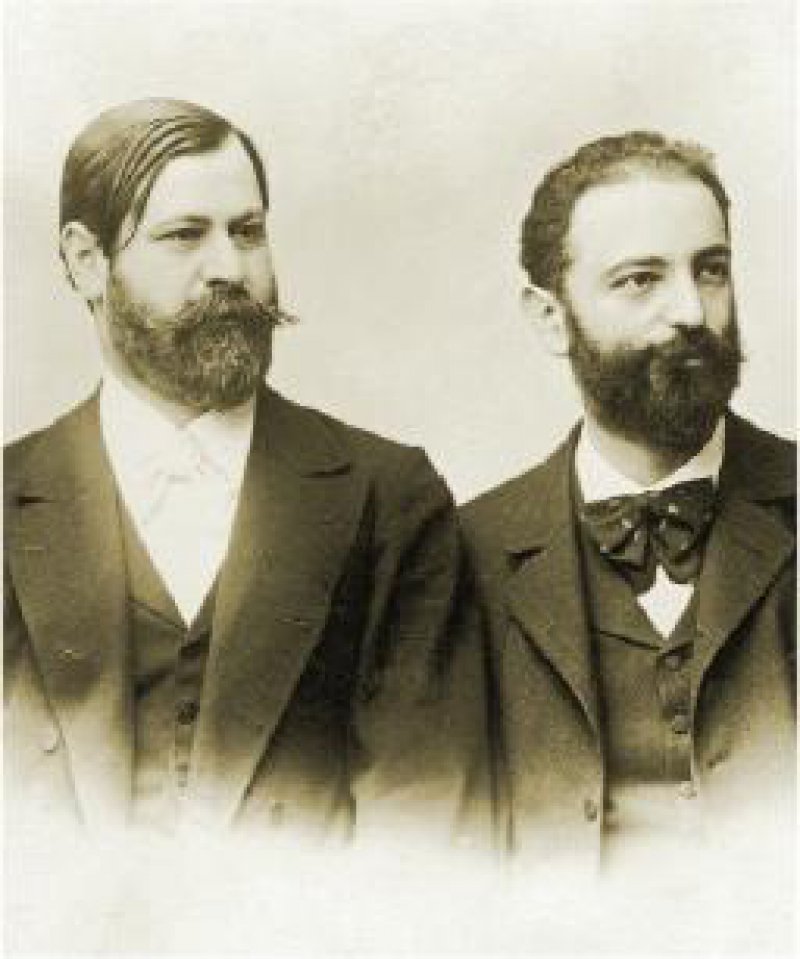

Friendship with Wilhelm Fliess

The most well-known photos of Freud often show him as an elderly man with white hair, looking wise and kind through his glasses. However, he also went through years of uncertainty and struggle while developing his theories, during which he faced strong opposition. One of his most important supporters during these difficult years was Wilhelm Fließ (1858–1928).

Freud and Fließ shared several cultural and religious similarities, as well as a medical background. Fließ was two years younger than Freud and, after finishing medical school, initially worked as a general practitioner. In 1887, he took an extended study trip through Europe, which was common at the time, and spent three months at the famous Vienna General Hospital. While there, he attended Freud’s lectures. The two eventually met in person at a social gathering hosted by Freud’s colleague, Josef Breuer.

After returning to Berlin, Fließ resumed his medical practice and specialized in nose and throat diseases. He had a certain “brilliance” that left a strong impression on Freud. Freud initiated a friendship with him and expressed a desire for scientific exchange and collaboration.

The “Fließ Period”

This marked a crucial period in the development of psychoanalysis, known as the “Fließ period,” which lasted from 1887 to 1902. Much of what we know about this time comes from 284 letters that Freud wrote to Fließ. Freud saw Fließ as a “resonator and amplifier of his ideas.”

They regularly exchanged their scientific writings, met periodically, and maintained an intense correspondence about their thoughts and projects. However, only Freud’s letters to Fließ have survived because, after their friendship ended, Freud destroyed the letters he had received from Fließ. This makes it difficult to determine how well Fließ understood Freud’s ideas. However, Freud’s letters suggest that Fließ was not only interested but also a thoughtful and critical reader.

At the beginning of the 20th century, a fundamental disagreement arose between them. Their views on the causes of neurosis increasingly diverged. Freud believed that neuroses were primarily caused by psychological factors, whereas Fließ, with his background as a surgeon, prioritized physical causes. This irreconcilable difference ultimately led to the end of their friendship.

Freud’s Personality

According to his daughter Anna, Freud’s most striking characteristic was his simplicity. He undoubtedly despised anything that made life unnecessarily complicated. This trait was evident even in the small details of his daily life. For instance, he never owned more than three suits, three pairs of shoes, and three sets of underwear.

Freud spoke openly and directly, without beating around the bush, but he could hardly be described as sensitive. At the same time, he made it clear that when it came to discussing his own person, only the topics he approved of were permissible. He left no doubt that he would take offense at any questions that went beyond those boundaries.

Freud’s “Black and White” Perception

The most striking discrepancy between Freud as a psychoanalyst and Freud as a private individual was his poor judgment of people in his inner circle. According to his biographer Ernest Jones, two of Freud’s strangest traits were his tendency toward indiscretion (on one occasion, for example, he told a patient everything Jones had confidentially shared with him about that very man) and his poor judgment of people.

“He sorted people into black and white characters,” Jones wrote, “which particularly puzzled his friends—after all, no one understood better than Freud how human nature is made up of a delicate blend of good and bad qualities. And yet, both consciously and even more so unconsciously, he divided those around him into ‘good’ and ‘bad’—or more precisely, into ‘liked’ and ‘disliked.’ And it was not at all unusual for him to move a person back and forth between these categories multiple times.”

While his opinion of the men in his social circle often shifted, his attitude toward women remained consistent. His letters suggest that he saw a woman’s primary role as being a guardian angel, tending to the needs and comforts of men. At the same time, he regarded women as more noble and ethically superior.

Leaving the Obscurity

During the pre-war years, Freud and his family lived in Vienna as if in a kind of ghetto. Freud had only two great passions: smoking and traveling. For ten years after discovering psychoanalysis, Freud suffered from what he called “intellectual loneliness.” There was almost no one with whom he could discuss his new insights. Years later, he referred to this period as his “splendid isolation.”

The isolation did not end abruptly but rather in a gradual transition. His essays began appearing more frequently in psychiatric journals, and by 1910, the professional world finally started engaging with his work through extensive reviews; the once-obscure Viennese doctor—whose name had initially been associated with scandalous theories—became an internationally respected scholar.

Rome as a Mother Symbol

For half his life, Freud had admired Rome, but some mysterious taboo kept him from visiting. Despite years of travel, he never got closer to the Eternal City than Lake Trasimeno. Interestingly, Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general whom Freud deeply admired, had also once halted his advance at this very lake, just 50 km from Rome’s gates. Freud saw this as a striking coincidence.

Ernst Jones interpreted this peculiar behavior through the lens of psychoanalysis. He saw it as an inhibition caused by Freud’s Oedipus complex—rooted in both father-hatred and mother-love. In his interpretation, Rome was the mother of all cities and thus a mother symbol. At first, Freud was unable to surpass his father symbol, Hannibal, who had been Rome’s greatest enemy. Only after years of self-analysis did Freud overcome his inhibitions and triumphantly enter the Eternal City.

For a similar reason, Freud’s closest collaborator, C.G. Jung, never entered Rome, despite his several journeys to Italy. It seems that Jung never overcame his Oedipus complex.

Moses of Michelangelo

Freud himself reflected extensively on the symbolic meaning of his visit to Rome in his letters, calling it “the highlight of my life.” Like any other tourist, he explored the city, but soon he encountered a new father figure materialized in Michelangelo’s statue of Moses in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli. Freud identified with Moses, perceiving his role as guiding humanity towards the promised land of psychoanalysis.

According to Jones, Freud flinched under the prophet’s furious gaze. His fascination with Moses resulted in an essay, “The Moses of Michelangelo,” a masterpiece of analytical thinking. In Freud’s view, Michelangelo captured the dynamic of decision-making when Moses decided not to rush down in anger to punish his people for falling into pagan rituals; a proof of great strength in which Moses suppressed emotions in favor of a higher cause.

Reaching the Psychiatric Community

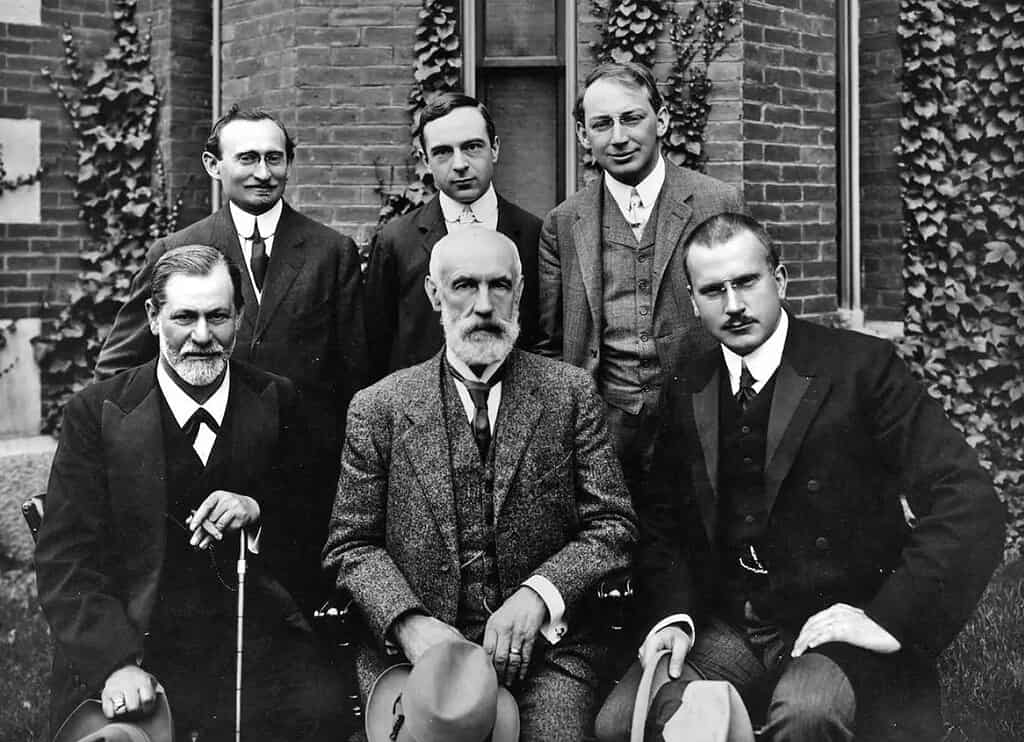

The publication of “The Interpretation of Dreams” aroused the interest of many doctors and educators far beyond the borders of Austria. Many students and fellow campaigners soon gathered around him, including psychiatrists from the most famous psychiatric hospital, Bürgholzli in Zürich, Switzerland, among them Eugen Bleuler, the medical director of the hospital, and Carl Gustav Jung, the chief of staff at the same hospital. Carl Gustav Jung became the closest collaborator of Freud over a period of 7 years.

Freud’s Lectures at Clark University

1909 was a pivotal year in Sigmund Freud’s life. In December 1908, Freud received a letter from Stanley Hall, the founding director of Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, inviting him to give lectures. Freud was to travel to Worcester with Sandor Ferenczi and C.G. Jung, who was invited later. Ferenczi, not officially part of the program, assumed the role of personal assistant for logistical planning. The small group, Freud, Jung, and Ferenczi, met in Bremen for the transatlantic crossing.

As the grand ship entered New York Harbor, Freud reportedly said, facing the Statue of Liberty, “They do not realize we are bringing them the plague.” To Freud, it was not his teachings but the suffering they aimed to combat that embodied the “plague”: the neuroses of modernity that flourished particularly in America.

Freud delivered five lectures in German, in a tone of serious yet casual conversation, leaving a profound impression on his American audience. With these five lectures, he achieved a breakthrough for psychoanalysis, which had until then been largely unknown in the United States, both among the academic audience and, subsequently, the interested public. Rightly regarded as Freud’s most concise introduction to his teachings, the lectures still provide a quick and comprehensive overview of all the central principles of psychoanalysis today.

The International Psychoanalytic Association

The involvement of several reputable psychiatrists from Zürich Burghölzli Psychiatric Hospital became a turning point in Freud’s biography and in the development of psychoanalysis. The active participation of Eugen Bleuler and Carl Gustav Jung in the psychoanalytical movement helped the psychoanalysis to move out of the restricted circle of Viennese psychoanalysts, all of them of Jewish origin and heavily attacked by conservative scientists. The final consolidation of the movement happened through the creation of the “International Psychoanalytic Association.” The International Psychoanalytic Association was founded in 1910 with Jung as its first president. Winning such reputable figures as Bleuler and Jung facilitated the spread of the psychoanalytical theory.

Freud, the Authoritarian Leader

Freud, despite his indisputable genius, was a difficult person. Over time, he repeatedly changed or expanded his psychoanalytic theory. However, he didn’t tolerate any deviation from his own theory by others. He treated those who modified his ideas as traitors. Over the years, his close collaborators and friends, such as Alfred Adler, Carl Gustav Jung, Wilhelm Stekel, and Herbert Silberer, left him.

Freud’s most friendly and professionally close disciples, the German psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Karl Abraham and Ernest Jones, also a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst from the UK, remained loyal to him for life, unlike many of his other followers. Abraham founded the “Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute,” which became one of the most important psychoanalytic centers in the German Empire. Ernest Jones helped the spread of Freud’s ideas in Canada and the US. He left Britain for Canada in 1908 and was lecturing in the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Toronto. In 1910, he initiated the foundation of the American Psychopathological Association, and in 1911, the American Psychoanalytic Association.

Freud’s Smoking Addiction

Freud began smoking cigars at age 24. He was reluctant to abandon this habit despite warnings from his friend Wilhelm Fliess, an ENT doctor. Freud used to smoke 20 cigarettes per day. Finally, in 1923, he was diagnosed with palate cancer and went through 34 surgical procedures. His cancer continued spreading, and his quality of life became unbearable. Freud died in 1939 in London through euthanasia.

Leaving Nazi-Occupied Vienna

Starting in 1933, the Nazis began destroying psychoanalysis in Germany. After the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society was dissolved. In 1938, the Freuds, as they were of Jewish descent, also faced persecution. On March 15, 1938, an SA troop stormed their home at Berggasse 19, intending to confiscate antiques. Martha Freud managed to get rid of the intruders by handing over her purse.

On March 22, 1938, Sigmund Freud was scheduled for interrogation. Since he had been suffering from cancer, his daughter Anna accompanied the Gestapo in his place. Due to the increasing threat posed by the Nazis, the Freuds decided to leave the Third Reich. Supported by his former patients and due to the international pressure, Freud left Vienna for London, taking with him all his furniture and belongings to London.

They arrived in London on June 6, 1938. There, Sigmund and Martha Freud lived in a house at 39 Elsworthy Road. Sigmund Freud passed away in London on September 23, 1939. His wife, Martha Beranys, died, unnoticed by the public, on September 23, 1939.

Freud’s Museums

Freud had lived, studied, and practiced psychoanalysis in Vienna. His former flat and private practice, located in Berggasse 19, were turned into Freud’s Museum. However, the rooms are empty, showing only the photographs of the former interior and only a few artifacts donated to the museum by Freud’s daughter Anna.

Another Freud museum was founded in London. Freud’s original furniture and his legendary couch are now publicly exhibited in the Freud Museum in London.

Sigmund Freud. Life and Discoveries. Summary

Sigmund Freud is credited with discovering unconscious mental activity through his intense study on hysteria and the inner logic of dreams. Between 1900 and 1910, he systematically developed his insights into the rules governing the interaction between the conscious and the unconscious into a theoretical framework, which he called psychoanalysis.

According to Freud, our unconscious is governed by the opposition of so-called drives (sexuality and aggression). This observation led him to formulate the structural model in which psychic tensions are understood as the result of conflicts between three central psychic structures: the Id, the Ego, and the Superego. Freud termed the driving force behind all psychic processes “libido,” which in his view was of purely sexual origin.

Despite its declining prominence, Freudian-style psychoanalysis is still in use in a wide variety of ways. It was also the psychoanalysis that paved the way for all contemporary methods of psychodynamic psychotherapy.

In his later works, Freud analyzed different aspects of society, such as culture, religion, and war. He became one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century. Freud’s ideas redefined Western thought and have been absorbed within popular culture and language.