Sigmund Freud’s development of sigmund freud psychoanalysis and his psychoanalytic theory laid the foundation for modern psychology. The work of sigmund freud revolutionized not only psychology but also other human sciences, including sociology, philosophy, and many areas of cultural life.

In fact, Sigmund Freud became one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. His ideas, including freud theory and sigmund freud psychoanalytical theory, were not only groundbreaking but also highly controversial. In 1900, he proposed that much of our behavior is driven by psychological processes we are not consciously aware of. Then, in 1905, he went even further, suggesting that children experience sexual feelings from a very young age. Few theories in psychology have sparked such intense reactions.

Freud’s broad education—including his knowledge of languages, literature, philosophy, and mythology—played a key role in the development of psychoanalysis and his theoretical contributions.

The pivotal point in Freud’s career was his internship in Paris, where he attended the lectures of Martin Charcot at Salpetriere. Charcot’s use of hypnosis and his famous demonstrations of hypnotized hysteric patients who, in a hypnotic state, developed physical symptoms showed that the root cause of hysteria was purely of psychic origin. This visit had a lasting influence on Freud’s later research.

Freud’s Use of Hypnosis

Back in Vienna, Freud started to use hypnosis in his private practice. He found out that people under hypnosis were not only susceptible to influence in their voluntary actions but also capable of recalling past experiences they could no longer remember when awake.

He also observed that under the influence of hypnosis, neurotic symptoms temporarily disappeared when a person was able to recall distressing past experiences. From this, a cornerstone of psychoanalysis emerged: the resolution of distressing and repressed experiences through their conscious acknowledgment.

However, Freud noticed that in patients treated with hypnosis, the neurotic symptoms reappeared after some time. He understood that hypnosis was not effective in resolving the fundamental conflict. Therefore, he soon abandoned hypnosis and developed his own method, which he called “psychoanalysis.”

Work with Josef Breuer

In 1889, Freud started to work with Josef Breuer, a Viennese doctor who became his friend, mentor, and collaborator. The first and most important case in the history of psychoanalysis was Berta Pappenheim, who later became known under the pseudonym Anna O. From 1880 to 1881, Breuer treated the young girl and recognized psychological causes behind her symptoms. He concluded that talking to the patient has a cathartic—i.e., cleansing—effect, which helps reduce neurotic symptoms. However, it was the young girl who called the therapy “talking cure.”

During the hypnosis, Anna O. reported on her symptoms, which were headaches, paralysis, dissociation, and states of anxiety. Uncovering the root cause of Anna O.’s problems, Breuer helped alleviate her symptoms. He introduced his treatment method to Freud. The ideas that emerged from that case had such a profound impact on Freud that he devoted the rest of his career to developing his own method of therapy, psychoanalysis.

Breuer and freud co-authored Studies on Hysteria, published in 1895, which is considered the founding text of psychoanalysis

Free Association

After giving up on hypnosis, Freud developed psychoanalysis based on his own method of interaction with patients, which he called “free association.” During free association, patients spontaneously expresses their thoughts and feelings. Later, the therapist analyses the patients’ “material” from their free associations. Unconscious material emerges in distorted, symbolic forms—such as in dreams, slips of the tongue, symptoms, and other psychological expressions, including the patient’s spontaneous thoughts. These manifestations require careful interpretation.

The most important tool in psychoanalytic work is the attentively engaged analyst, who remains open to insights from his own unconscious. Freud called it “evenly suspended attention,” meaning the analyst remains open and receptive without steering the conversation in any particular direction.

Freud’s Topological Model of the Psyche

Freud did not discover the concept of the “unconscious.” Psychologists and psychiatrists were already aware of deeper layers of the psyche before him. However, Freud was the first to develop a practical method of psychotherapy, a comprehensive theory of the psyche’s structure, and a set of psychoanalytic terms still in use today.

The distinction between consciousness and the unconscious is a central concept in psychoanalysis. Originally, Freud asked where psychological processes take place and defined three locations: the consciousness, the preconscious, and the unconscious. Consciousness is something everyone knows from personal experience; it refers to the awareness of one’s own existence.

Freud defined the preconscious as a “psychic space” containing material that is not currently conscious but can be brought into consciousness, such as memory, recollections, vocabulary, and learned skills. On the other side, he described the unconscious as a part of the psyche an individual doesn’t have any access to.

Timeless and Spaceless Notion of the Unconscious

Freud saw the unconscious as timeless and spaceless, with timelessness being its essential feature. By timelessness and spacelessness, he meant a state that has no temporal or spatial order. He based this thesis on his empirical findings from psychoanalytic experience. He noted that healing traumas is based on recognizing their root causes and addressing them, which enables healing. In the pattern of repetition of unconscious motifs, he observed that these elements are preserved in their original form, leading him to conclude that they are timeless and spaceless.

The Ego and the Id

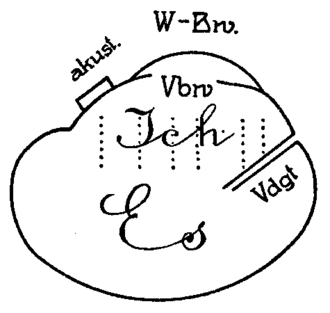

According to Freud’s concept, the psyche is made up of different parts, or “instances.” He used a spatial model to explain the relationships between those parts.

In his paper, The Ego and the Id, he shows this idea with a drawing. The psychy of an individual develops from the Id under the influence of the external world, with the Ego forming superficially on top of it.

For Freud, the Id is unconscious and is entirely driven by the pleasure principle. The Id includes contents and feelings that arise from the drives. It is the source of drive energy, the libido. The Id is also where repressed material is stored, meaning content and feelings that are kept from becoming conscious due to the Ego’s resistance.

Fundamental Assumptions of Psychoanalysis

A basic assumption of psychoanalysis—and depth psychology as a whole—is the existence of the unconscious. Individuals are almost entirely unaware of the unconscious, yet it largely influences or even determines people’s actions. This idea of the unconscious has far-reaching effects, challenging the rationalist belief that humans act rationally by making conscious decisions. For Freud, the impossibility of truly free action was evident. The very idea that a human being could act freely is fundamentally at odds with this perspective.

The second fundamental hypothesis states that psychological processes are essentially causally determined, meaning they are subject to the law of cause and effect. Freud was raised in the materialistic spirit of the 19th century and remained largely faithful to that mode of thinking throughout his life. He embraced the typically materialistic reductionism that reduces the mental to the psychological and the psychological to the organic.

Consequently, the psychological life is ultimately mere outflows of matter and cannot exist independently of it. Within this framework, the notion of an individual soul—capable of surviving apart from the body after physical death—is inconceivable.

Contrary to Freud, C.G. Jung’s psychology proposes a noncausal and nonmaterial nature of the psyche. However, it was and still is Freud’s psychology reflecting the causal dogma of today’s science.

The Psychoanalytical Process

Psychoanalysis is an independent therapeutic method, a so-called “talking cure.” It was the first effective treatment for mental illnesses and thus also the first form of psychotherapy. At its core, psychoanalysis and its later modifications, it is a conversation. However, this conversation is governed by specific sett of rules making it different from ordinary talk. The main rule, is to encourage the patients (or “analysands”) to express everything they feel, sense, or think—no matter how uncomfortable, embarrassing, inappropriate—freely and without censorship. Unconscious material surfaces in distorted, symbolic forms—in dreams, slips of the tongue, symptoms, and other psychological expressions, as well as in the patient’s spontaneous thoughts. These expressions require careful interpretations.

The goal of psychoanalysis is to uncover and neutralize the effects of unconscious harmful content in order to promote healing. Contrary to common criticism, psychoanalysis does not focus solely on reprocessing unresolved childhood experiences. While early life experiences and trauma can have a lasting impact, psychoanalytic therapy also addresses unconscious content from the present and its disruptive effects on people’s life.

Transference and Contratransference

No matter how attentively and neutrally the analyst engages with the patient, it is inevitable that certain aspects—such as the analyst’s age, gender, or way of speaking—will evoke emotional reactions in the patient. These emotional responses are known as transference, and their roots typically lie in the patient’s past experiences. In the patient’s fantasies, the analyst may take on the roles of important figures. For example, a strained relationship with a father may be projected onto a male analyst, surfacing as hostility or mistrust. It is the analyst’s role to recognize these transferences and help neutralize them through interpretation.

Conversely, the analyst is also affected by the patient. The patient may stir up emotional responses in the analyst—known as countertransference—which often stem from the analyst’s own unresolved inner conflicts. A core task of the analyst is to become aware of these reactions and to reflect on them to prevent their interference with the therapeutic process.

Within the dynamic of transference and countertransference, unconscious expectations and roles are enacted between patient and analyst. These interactions bring to the surface old, unresolved emotional conflicts, allowing them to be re-experienced and ultimately worked through within the therapeutic relationship.

Transference does not only occur in therapy—it exists in almost every human relationship. However, in psychoanalysis, the analyst becomes a kind of projection screen for the patient’s inner world.

Resistance in the Analytical Process

In psychoanalysis, the term resistance refers to all the unconscious forces and defense mechanisms that prevent repressed material from becoming conscious. What may appear as the patient’s random or spontaneous thoughts—so-called “free associations”—are in fact not accidental. Instead, they reveal the deterministic structure of the unconscious. In psychoanalytic terms, determinism means that “everything has meaning,” and that the present psychological experience is shaped by both personal and collective past experiences.

Thus, the task of psychoanalysis is to overcome the resistance and to uncover, reconstruct, and interpret the unconscious layers of meaning from a person’s life history. This effort can be described as a “struggle for memory.” The psychoanalytic process, as a shared experience of feeling, thinking, and speaking, is fundamentally an attempt to broaden and transform perception.

Credentials of a Psychoanalyst

The specific emotional relationship between analyst and patient—particularly the roles of transference and countertransference—has gained increasing significance over the course of psychoanalysis’s development. As a result, every psychoanalyst must complete extensive theoretical and practical training spanning several years. A core element of this training is undergoing a long-term personal training analysis, allowing future analysts to experience the psychoanalytic process firsthand.

Weekness of Freud’s Psychoanalytical Theory

Freud was a neurologist and possessed little knowledge in the field of psychiatry. His psychiatric experience was limited to a few weeks of training in one of the psychiatric hospitals in Vienna.

Freud’s patients, mostly women, belonged to the Viennese upper class. This part of society adhered to the rigid morality of the 19th century, called the “Victorian era.” The reason that the symptoms of hysteria appeared, especially in young girls and women, was the conservative nature of the society, which prohibited any expression of erotic desires, especially in higher-class women. This led to internal conflicts between societal values and drives. Such inner tension created by repressed sexuality was the triggering factor for the onset of neurosis in a large percentage of upper-class females.

Based on the observation of his upper-class female clients, Freud generalized and put sexuality as the cornerstone of the neurotic conflict and sexuality as the only origin of neurosis.

Sigmund Freud Development of Psychoanalysis. Summary

Sigmund Freud is probably the most debated and misunderstood figure in the history of psychology. His psychoanalytical theory revolutionized the humanistic sciences and the knowledge of our human nature. Despite the controversies, his psychoanalytic theory remains the cornerstone of psychological thought.

Throughout his life, Freud continued to develop, refine, and revise his concepts. This process was carried forward by Freudian psychoanalysts, resulting in several modifications of the original method. Psychoanalysis became the foundation from which various forms of psychotherapy evolved—approaches referred to as “in-depth psychotherapy” or “psychodynamic psychotherapy.” All of these psychotherapeutic technics share a common focus: exploring the unconscious and its influence on an individual’s perception, interpretation, and interaction with themselves and others.

Since Freud’s time, psychoanalysis has extended its methods to the depth-psychological interpretation of literature, religion, mythology, and other collective and cultural phenomena. Notable examples of this include Freud’s essays such as The Moses of Michelangelo, which analyzes the famous sculpture, and Civilization and Its Discontents, which explores the tension between individual instincts and societal demands.

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Dr. Gregor Kowal studied human medicine at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg, Germany, where he also earned his doctoral degree (PhD). He completed his specialization in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy with the Medical Chamber of Koblenz, Germany. In the following years, he held positions as Head of Department and Medical Director in various psychiatric hospitals across Germany. Alongside his clinical responsibilities, he served as a consultant expert for the Federal Court in Frankfurt, providing psychiatric evaluations in legal cases. Since 2011, Dr. Kowal has been working as the Medical Director of CHMC, the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Dubai, UAE. His specialist training includes extensive expertise in biological psychiatry and psychodynamic psychotherapy.