The Self in Jungian psychology highlights the concept of personality development, which plays a central role in both Jungian and Freudian psychology.

According to Freud‘s psychoanalytical theory, the unconscious Id is present from birth and is made up of basic instincts and desires. The Id operates solely according to the pleasure principle—it seeks pleasure and avoids pain. Freud described the Id as “the great reservoir of libido,” meaning it contains the energy of our desires—primarily life instincts such as the drives for pleasure, survival, and reproduction. As we grow, the Ego—our self-awareness and the conscious part of our personality—develops out of the Id.

The Self in Jungian psychology is a central idea that differentiates Jung from Freud. The concept of the Ego is largely the same in Jungian psychology. However, Freud and Jung had different views on the content of the unconscious. Freud saw the Id (the unconscious part of the psyche) as a container of blind drives and the source of libido (life energy). The concept of Self in C.G. Jung psychology goes beyond this view. Jung introduced the Self, which, like the Id, is unconscious. The key difference is that Jung understood the Self as a living inner entity, equipped with the wisdom of our species. For those asking, what is the Self in Jungian psychology, it is the organizing principle of the psyche, integrating both conscious and unconscious aspects to guide us toward wholeness.

The Collective Unconscious and the Self

The concept of the Self cannot be understood without referring to the collective unconscious.

In a lecture „The Concept of the Collective Unconscious” hold in London on October 19, 1936, Jung described his concept of the collcetive unconscious:

“My thesis, is as follows: in addition to our immediate consciousness, which is of a thoroughly personal nature and which we believe to be the only empirical psyche …, there exists a second psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals. This collective unconscious does not develop individually but is inherited. It consists of pre-existent forms, the archetypes, which can only become conscious secondarily and which give definite form to certain psychic contents.”

Jung’s Two Personalities and the Concept of the Self

In typical Jungian fashion, Carl Gustav Jung was both the object and the observing subject of his own psychic processes. The concept of the Self is rooted in his childhood experiences and his unique ability to observe and notice phenomena that others often overlook.

Since his early chialdhood Jung felt as if he was made up of two different personalities, which he called ‘No. 1’ and ‘No. 2′. No. 1 was the ordinary boy who visited school and tried to deal with everyday life. No. 2, on the other hand, felt much older and was disconnected from normal society. This part of him, a mysterious figure, felt close to nature, animals, and dreams.

In his autbiography “Memories Dreams, Reflections” Jung described his childhood revelation:

“Somewhere deep in the background I always knew that I was two persons. One was the son of my parents, who went to school and was less intelligent, attentive, hard-working, decent, and clean than many other boys. The other was grown up old, in fact skeptical, mistrustful, remote from the world of men, but close to nature, the earth, the sun, the moon, the weather, all living creatures…

As soon as I was alone, I could pass over into this state. I therefore sought the peace and solitude of this “Other,” personality No. 2. The play and counterplay between personalities No. 1 and No. 2, which has run through my whole life, has nothing to do with a “split” or dissociation in the ordinary medical sense. On the contrary, it is played out in every individual. In my life No. 2 has been of prime importance, and I have always tried to make room for anything that wanted to come to me from within. He is a typical figure, but he is perceived only by the very few. Most people’s conscious understanding is not sufficient to realize that he is also what they are.“

MDR, p. 45

Number 1 and 2. The Ego and the Self

As he became a psychiatrist, Jung realized that these two sides were not unique to him. However, Jung’s uniqueness was his ability to connect with his unconscious to a much greater extent than most people. Jung believed that everyone has both aspects within his personality, which he described as the Ego (No. 1) and the Self (No. 2). Based on this assumption and his own experience of inner transformation, he developed the concept of personality development, which he called “individuation.”

For the rest of his life, Jung was preoccupied with the dynamics of personal transformation and growth. He was one of the few psychotherapists in the twentieth century to maintain that development extends beyond childhood and adolescence, through mid-life, and into old age. The process of individuation, in which the Ego explores the Self and gains a higher level of consciousness, encompasses the entire lifespan.

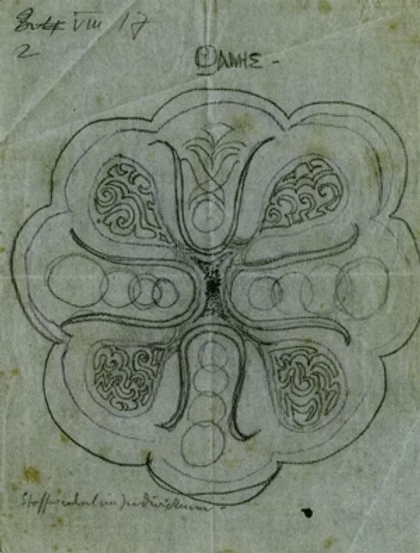

Mandala. The Symbol of the Self

During his military service between 1918 and 1919, Jung began a daily practice of drawing circular symbols in a notebook. These figures, which he later identified as mandalas, appeared to reflect his inner psychological state. By engaging with this process, he was able to observe subtle shifts in his psyche over time.

Through continued work with these drawings, Jung gradually came to see the mandala as a symbolic representation of psychological wholeness. It served, in his view, as a visual expression of the Self—a central and unifying element of the personality that encompasses both the conscious and unconscious dimensions of the psyche.

The process of drawing mandalas prompted him to reflect on the nature of psychological development. Rather than viewing it as a process led by the Ego, Jung realized that true inner growth involved relinquishing the ego’s dominance. The recurring structure of the mandala, with its focus on symmetry and a central point, revealed to him a deeper pattern—one in which all personal experiences revolve around a central core.

Over time, Jung came to understand this central point as the Self, and he saw the mandala as a symbolic path leading toward it. This insight contributed significantly to his concept of individuation: the process by which a person gradually integrates the various parts of the psyche and moves toward greater inner unity. According to Jung, psychological growth does not proceed in a straight line but rather in a circular, spiraling pattern—a continual return to and deepening around the Self.

Other Symbols of the Self

Based on his cultural-historical and dream-psychological studies, C. G. Jung identified several symbolic representations commonly associated with the Self. As the central archetype of order, the Self is often symbolized by geometric shapes. One of the most typical figuers is the mandala; the others are the cross, circle, or square. The Self also appears through polar opposites such as Yin and Yang, Goddess and God, or King and Queen. Additionally, the Self may be also represented by animal figures like elephants, lions, or bears.

The Ego and the Self

In Jungian psychology the Ego is the center of our consciousness, whereas the Self encompasses the entire psyche, its conscious (the Ego) and unconscious components, representing the psyche as a whole.

For Jung, the Self is the archetype of order, governing and organizing the psyche. Similar to Freud’s idea that the Ego emerges from the unconscious Id, Jung also believed that the Self is the primary entity present from birth from which the Ego developes.

The Self lies at the core of who we are, but it can never be fully grasped, since the Ego is only a small fragment of the greater whole and therefore cannot comprehend the full dimension of the Self.

The Ego-Self Relationship

If the Self remains entirely unconscious, the Ego may mistake itself for the whole psyche—a condition Jung viewed as dangerous for mental health, and referred to as the “hubris of consciousness.” Other particular risk in the Ego–Self relationship is that the Ego could be overwhelmed or even absorbed by the Self. In such a case, consciousness may be overtaken by unconscious forces, leading to serious psychological disturbances including psychosis.

The Ego must therefore navigate a delicate balance: avoiding both isolation from the Self and being overpowered by it. Under normal psychological conditions, both tendencies are present—the dominance of the Self and the Ego’s tendency to overestimate its own importance.

The Self and the Shadow

Jung acknowledged that part of the Self has also a destructive side, which he called the Shadow. This “dark” side of the human psyche also belongs to the wholeness of the Self. Within the Self, light and shadow form a paradoxical unity. In contrast, the Christian worldview tends to divide good and evil into two irreconcilable opposites, rather than seeing them as integrated parts of a greater whole.

Individuation. The Realization of the Self

The gradual process by which the Ego becomes aware of the contents of the Self is what Jung called self-realization or individuation. From the beginning, the Self guides and regulates this inner process of transformation. It often manifests in symbolic form in dreams, which is why dream interpretation is considered by Jung to be one of the primary paths toward individuation.

Jung also emphasized that true self-knowledge is not merely an individual or internal matter—it is deeply social. Unlike the “mass man,” who is easily influenced and manipulated by political forces, societal trends, or fashions, the individuated person gains a differentiated and conscious perception of others and the surrounding world.

The Self in Jungian Psychology. Summary

In Jungian Psychology the Self contains both unconscious and conscious aspects of the psyche. It includes all of a person’s inherent potentials and predispositions. It is the foundation of consciousness, from which the Ego arises. The Ego—our sense of “I”—emerges from the Self in early childhood.

According to Jung, the Self is the “totality that transcends the Ego.” The Ego, in contrast, is the conscious part of the Self, our self-awareness, but at the same time just a small fragment within a larger whole. The Ego derives its content and functions from the Self but remains subordinate to it, much like the erth revolves around the sun. Because the Self can never be fully grasped by the Ego (our consciousness), Jung referred to it as the “unknown totality of the human being.”

DR. GREGOR KOWAL

Dr. Gregor Kowal studied human medicine at the Ruprecht-Karls-University in Heidelberg, Germany, where he also earned his doctoral degree (PhD). He completed his specialization in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy with the Medical Chamber of Koblenz, Germany. In the following years, he held positions as Head of Department and Medical Director in various psychiatric hospitals across Germany. Alongside his clinical responsibilities, he served as a consultant expert for the Federal Court in Frankfurt, providing psychiatric evaluations in legal cases. Since 2011, Dr. Kowal has been working as the Medical Director of CHMC, the Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy in Dubai, UAE. His specialist training includes extensive expertise in biological psychiatry and psychodynamic psychotherapy.

Read More about Jungian Psychology

- Carl Gustav Jung. A Short Biography

- Psychology of Carl Gustav Jung

- The Collective Unconcious

- The Individuation

- The Archetyps

- Archetyps. The Redicovered Theory

- The Ego and The Persona

- The Shadow

- The Animus and The Anima

- The Archytypal Neurosis

- Jungian Psychology and the Brain Structure

- Brain Evolution and Psychology

- Synchronicity

- Jungian Dream Analysis

- Freudian and Jungian Models of the Psyche

- What is Psychoanalytical Psychotherapy

- C.G. Jung and Otto Gross

- C.G. Jung Psychological Types

- C.G. Jung’s Word Association Test

- The Spiritual Aspect of the Psyche (Jungian View)