Obesity refers to an excess of body fat. Measuring fat percentage is ideal. Since fat measurement is complex, obesity is usually assessed using BMI. A BMI of 25-30 indicates overweight, posing no risk without additional factors. Obesity starts at a BMI of 30; a BMI over 40 indicates morbid obesity. Debate exists on whether obesity is a disease or just a health risk factor. Obese individuals often experience limited mobility and reduced physical endurance. This restriction worsens inactivity, perpetuating a cycle that increases weight.

Schedule an Appointment with Our Leading Psychiatrist, Dr. Kowal

Call CHMCMedical treatment is generally indicated for a BMI of 30 or higher. Recent studies show less life expectancy reduction in obesity than previously thought. Excess mortality significantly depends on gender, appearing for men at BMI 36. For women, this risk starts at BMI 40 and decreases post age 50.

Obesity in Childhood and Adolescence

Defining overweight and obesity in children and adolescents must account for age- and sex-specific changes. A BMI of 25 indicates overweight, and over 30 indicates morbid obesity in adults. Since these BMI thresholds are risk-based for adults, this approach ensures a smooth transition from childhood obesity definitions to those for adults and helps guide appropriate obesity treatment strategies.

In the past 30 years, the greatest increases in obesity prevalence worldwide have been observed among children and adolescents. In Germany, depending on the definition used, 10–20% of school-aged children are now overweight. The highest increase rates are seen among obese girls. The severity of childhood obesity has also worsened; obese children and adolescents today are heavier than 20 years ago. Common obesity symptoms include excessive weight gain, fatigue, and difficulty in physical activity. Obesity is often observed at very young ages but usually comes to medical attention during prepuberty due to increasing severity and chronicity. In some cases, genetic conditions like Prader-Willi syndrome may contribute to early-onset obesity and require specialized care.

Prevalence of Obesity in Childhood and Puberty

In Western countries, depending on the definition used, 10-15% of school-aged children are now overweight. The highest increase rates are seen among obese girls. The severity of obesity has also worsened; obese children and adolescents today are heavier than 20 years ago. Obesity is observed at very young ages but often comes to medical attention during pre-puberty due to increasing severity and chronicity. About one-third of childhood obesity cases persist into adulthood.

Diagnosis of Obesity

Obesity as an independent disorder is not classified in ICD or DSM systems. However, classifications exist when reactive factors contribute to obesity:

Classification Systems

- F50.4: Eating episodes in other mental disorders

- Excessive eating caused by stress (e.g., grief, accidents, surgeries, emotional events).

- Obesity as a cause of psychological issues may be diagnosed under various codes:

- It can increase sensitivity about appearance and lower confidence in relationships.

- Body size perception may become exaggerated.

Relevant diagnostic codes include:

- F38: Other mood disorders

- F41.2: Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder

- F48.9: Unspecified neurotic disorder with obesity

Additional classifications include:

- F66.1: Obesity caused by medication

- F50.8: Other eating disorders (e.g., fasting in obesity, psychogenic appetite loss, non-organic pica in adults).

Risk Factors of Obesity

No specific personality traits unique to obese individuals have been empirically proven. Early-onset obesity is generally multifactorial, with overweight parents being the greatest risk factor. Genetic influences, emotional eating, and family-learned behaviors and eating habits also contribute significantly. Weight loss motivation can be especially difficult to maintain in such environments, further complicating long-term success.

Additional risk factors include low socioeconomic status, being raised by a single parent, being an only child, a high-fat diet, and excessive screen time. A small number of hereditary syndromes, such as Prader-Willi syndrome, are associated with severe obesity and often intellectual disabilities. In some cases, medical interventions, including appetite suppressants, may be considered as part of a supervised plan. Support from an obesity clinic in Dubai can provide the specialized care needed for individuals facing complex weight-related challenges.

Gender and Obesity

Men perceive themselves as slightly overweight only when 15% above their ideal weight, whereas women consider themselves obese at that point. Boys are less likely than girls to view themselves as overweight or consider dieting. During puberty, being overweight is less stigmatized for boys. Increased body size is often attributed to developing muscles, reflecting the social ideal of growing masculinity. For girls, the development of female curves and fat deposits conflicts with modern female slimness ideals. Boys may also cope better with puberty challenges because their sexual maturity typically occurs two years later than girls’.

The lower prevalence of eating disorders in men appears influenced by several key factors. Men face less societal pressure to conform to the prevailing slim ideal. Articles about dieting are published about ten times less frequently in magazines targeting men than in women’s magazines.

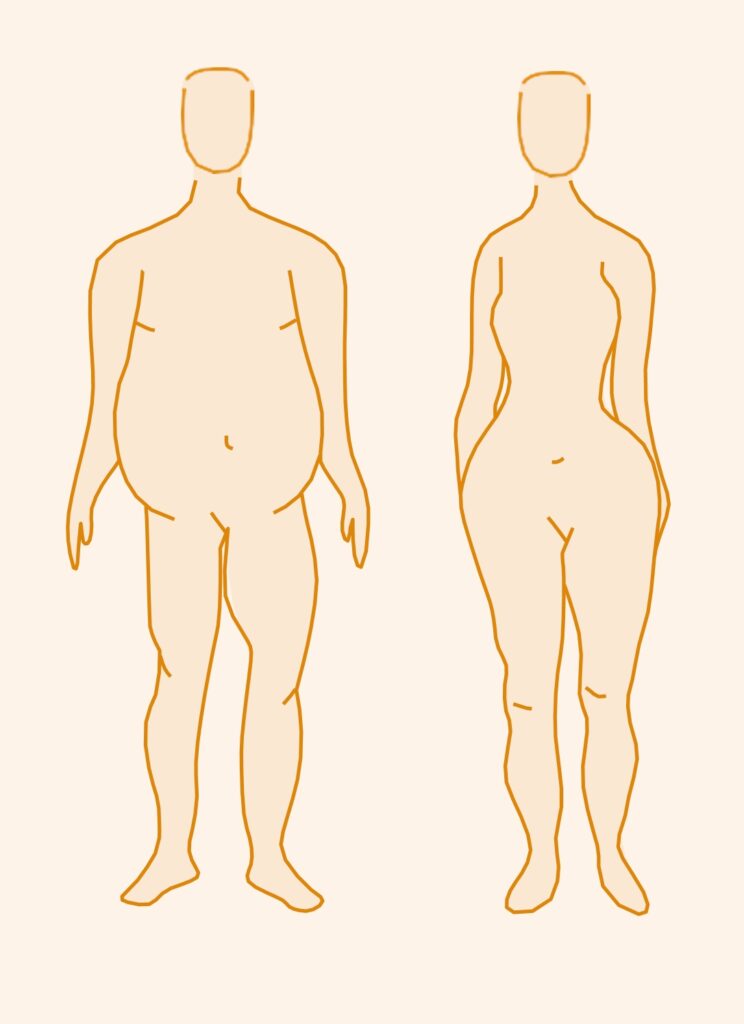

Gynoid and Android Obesity

From a biophysiological perspective, obesity is classified into gynoid (pear-shaped) and android (apple-shaped) forms. Both types occur in men and women, but gynoid is more common in women, android in men. The distinction depends on the Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR):

Gynoid form:

- Subcutaneous fat concentrated in thighs and buttocks

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) below 0.8

Android form:

- Visceral fat in the upper body, especially the abdominal area

- Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) above 1

WHR, particularly in women, has more impact on health risks than absolute weight. Visceral fat in android obesity increases risks of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In gynoid obesity, these risks are similar to those of normal-weight individuals. Visceral fat increases free fatty acid flow to the liver, reducing insulin clearance and causing hyperinsulinism.

Subcutaneous fat in gynoid obesity resists weight loss more than visceral fat.

Hyperinsulinism leads to insulin receptor down-regulation, insulin resistance, and impaired glucose tolerance. Calorie restriction primarily reduces abdominal fat, aiding weight loss for android obesity more effectively. These differences should guide counselling and treatment decisions for overweight individuals.

Functional Backgrounds of Obesity

- For some, using food as a reward was a family tradition, shaping future habits.

- Food may also be used to cope with loneliness, boredom, frustration, or inner emptiness.

- For some, especially women, being overweight provides emotional protection or a boundary (e.g., fear of sexuality).

- For men, being overweight is sometimes associated with power and dominance.

Cultural myths and irrational beliefs about “good food” and overweight people can also play a role.

Examples include:

- “If you work hard, you must eat well.”

- “The nerves need to swim in fat.”

- “The way to the heart is through the stomach.”

It should be noted that frequent weight fluctuations may reduce life expectancy more than consistent obesity. Sometimes, improving physical health is better achieved by changing diet composition rather than weight loss.

Two Obesity Groups from Therapeutic Point of View

From a motivational and therapeutic perspective, obese individuals can be broadly divided into two groups:

Groups of Individuals Developing Obesity

From a motivational and therapeutic perspective, obese individuals can be divided into two groups:

The first group includes overweight individuals with little psychological distress, often referred to as the “Falstaff type” in literature. These individuals are often overweight since childhood, feel connected to a family tradition, and regularly consume excessive amounts of high-calorie foods and sweets, perceiving their eating habits as normal. Their desire for treatment usually arises from external pressure rather than personal motivation.

The second group experiences significant distress and a strong desire for treatment. They often have a history of unsuccessful dieting attempts, including the use of appetite suppressants, laxatives, and diuretics. Many struggle with severe binge eating episodes, perceived as uncontrollable, sometimes followed by vomiting.

Frequent weight fluctuations can sometimes reduce life expectancy more than consistent obesity. Improving physical health is occasionally better achieved by altering diet composition rather than weight loss.

Physical Consequences of Obesity

Due to binge eating and weight control measures, bulimia can lead to severe physical complications.

Internal medicine complications:

- Acute gastric dilation, risking stomach rupture

- Electrolyte imbalances, especially hypokalemic alkalosis

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis

- Dehydration

- Edema

- Clubbed fingers

- Diarrhea

- Chronic constipation, potentially leading to intestinal paralysis

- Tachycardia and sweating (often caused by appetite suppressants)

- Kidney damage

- Vitamin deficiencies

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

Endocrinological and gynecological complications:

- Menstrual irregularities

- Anovulatory cycles

- Amenorrhea

- Altered vasopressin (ADH) levels

- Changes in aldosterone levels

Loss of impulse control creates a cycle of self-devaluation and guilt, often intensified by externally induced guilt, leading to rejection of their own body and, in some cases, outright hatred for it.

Surgical complications:

Increased rates of abscess formation, infections, wound healing problems, higher intraoperative risks, elevated anesthesia risks, increased postoperative pulmonary risks due to obstructive ventilation disorders, varicose veins, and abdominal or inguinal hernias.

Orthopedic complications:

Premature joint wear, herniated discs, lower back pain, femoral neck stress fractures, knee instability, and overloading of the feet lead to splayfoot and hallux valgus formations.

Gynecological complications:

Cycle irregularities and pregnancy risks.

Andrological complications:

Impotence.

Psychological Consequences of Obesity

Social withdrawal, lack of enjoyable activities, reduced social skills, increased use of food for coping, and lack of physical activity.

Causes of Obesity

In recent years, genetic factors have been increasingly recognized as significant in obesity development. Body weight, fat mass, and individual responses to a rich diet are largely influenced by genetics.

The reasons for obesity are less clear today than in past years. It has not been empirically proven that obese individuals consume above-average amounts of food. The “energy balance principle,” which claims obese individuals consume more energy than needed, is not statistically valid for the group as a whole. Similarly, the “externality hypothesis,” suggesting obese individuals are highly reactive to external cues and overeat in response, lacks empirical support.

Eating Disorders and Diabetes Mellitus

The differential diagnosis of poorly controlled diabetes mellitus includes insulin resistance from circulating insulin antibodies, gastrointestinal absorption issues due to altered digestion, and comorbid endocrine or metabolic disorders. The possibility of coexisting diabetes and an eating disorder is often overlooked.

Prevalence of Comorbid diabetes and Obesity

Depending on diagnostic criteria, the prevalence of comorbid diabetes and eating disorders ranges from 0 to 35%. Studies predominantly focus on insulin-dependent diabetic patients.

Most individuals develop the eating disorder after the onset of diabetes. Women are significantly more affected than men. Compared to the general population, anorexia and bulimia are not more prevalent among young insulin-dependent diabetics.

However, subclinical eating disorders that do not meet all ICD criteria are commonly observed. These disorders significantly impact metabolic control. From a diabetological and psychosomatic perspective, deliberate insulin dose reduction to promote weight loss via renal glucose and fluid excretion is notable. This weight-loss method carries a high risk for later diabetic complications.

Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus, the Dual Disorder

Juvenile diabetes is often diagnosed around ages 11–12, coinciding with the vulnerable pubertal phase. This stage is marked by role uncertainty, self-doubt, emotional instability, and challenges with boundaries and conflict. Accepting one’s body is crucial for developing a positive self-image during adolescence. Key psychological developments in this phase include self-reflection, detachment from family, and striving for autonomy. Diabetes management often conflicts with these developmental steps due to its rigid therapeutic demands. The daily tension between autonomy and dependence profoundly influences adolescents’ individuation process. Eating disorders may arise as expressions of overwhelm or rebellion against dietary restrictions and “being different.” The paradox of the “dual disorder” lies in patients using substances to endure or enhance their eating disorder.

Diagnosis of Dual Disorder

Suspected comorbidity with an eating disorder arises in cases of persistent metabolic instability, particularly in girls and women.

The following criteria are relevant and should be considered during diagnosis:

- Chronic blood sugar dysregulation without identifiable diabetic causes (brittle diabetes).

- Metabolic instability occurs years after initial diagnosis, therapy training, and relative metabolic stability.

- High-risk group: young girls and women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (Type I).

- Physical signs of an eating disorder: weight fluctuations/cachexia, amenorrhea, dental issues, constipation, and electrolyte imbalances.

- Psychological signs of an eating disorder: self-esteem issues, preoccupation with body and weight, weight phobia.

- Diagnosis supported by reviewing the diabetes logbook and patterns of blood sugar dysregulation.

Risks of the Dual Disorder

Deliberate weight loss to the point of cachexia or alternating excessive eating with weight loss methods such as vomiting, fasting, or glucosuria makes stable blood sugar management impossible. This significantly increases the risk of irreversible diabetic complications.

Therapeutic Considerations

The need for inpatient treatment solely due to comorbidity is not necessarily indicated. The decision between inpatient or outpatient psychotherapy depends on the psychopathological findings and psychosocial situation. Therapy aims to address both the eating disorder and a return to an appropriate diabetes diet and insulin regimen. Eating disorders and diabetes mellitus cannot be treated in isolation, as they are often intertwined. Both are influenced by problematic illness processing and tend to reinforce each other. The therapeutic approach will determine how much control-orientated measures (weighing, tracking, journaling) are used. In any case, documenting blood sugar levels, mandatory for diabetics, should also be central in psychotherapy. Patients must learn to regulate their food intake largely through cognitive factors, promoting behaviours that may encourage eating disorders. Maintaining near-euglycemic metabolic balance requires strict dietary management through extensive cognitive control.

Patients should avoid foods containing rapidly absorbable carbohydrates and counteract obesity to reduce insulin resistance. These diabetes-specific strategies present significant risk factors for the development and perpetuation of eating disorders. The interdependence of diabetes and eating disorders remains unclear. The frequent onset of eating disorders years after diabetes diagnosis suggests a facilitation aspect linked to diabetes management strategies. To understand more about this connection and its impact, visit our detailed guide on anorexia treatment.

Psychological Mechanism behind Obesity

Based on the described problems and conflicts, the eating disorder may serve the following functions:

- It represents an individual response to a chronic illness with inadequate coping strategies.

- It develops as part of a neurotic process shaped by the specific challenges of diabetes.

- It constitutes a dual disorder, where a diabetic patient also faces severe psychological issues expressed through the eating disorder.

- Poor metabolic control in diabetics with eating disorders reflects problematic management of a chronic illness impacting both present behaviour and future health.

Treatment for Overweight and Obesity in Dubai. Summary

A BMI of 25 indicates overweight, and over 30 indicates obesity. Since these BMI thresholds are risk-based for adults, this approach ensures a smooth transition from childhood and adolescent obesity definitions to those for adults.

About one-third of childhood obesity cases persist into adulthood. Early-onset obesity is generally multifactorial, with overweight parents being the greatest risk factor. Genetic factors and family-learned behaviours and eating habits also play a role. Additional risk factors include low socioeconomic status, being raised by a single parent, being an only child, a high-fat diet, and excessive screen time.

In the past 30 years, the greatest increases in obesity prevalence worldwide have been observed among children and adolescents. Learn more at CHMC Dubai.